A turning tide for two-way CSAs?

Sovereign derivatives users have historically refused to post collateral, but this is creating huge funding and capital obligations for banks. Higher prices have forced some sovereigns to change tack – and others may be about to follow suit. By Matt Cameron

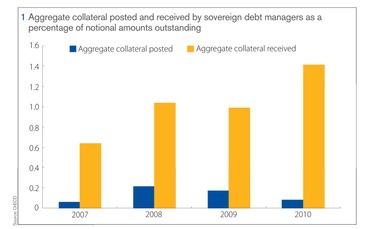

Sovereign clients have always been very clear about how they want to trade derivatives: they don’t expect to post collateral, but they might want it from their bank counterparties when trades go in their favour. There has been a big push to preserve this status quo – in Europe, for example, sovereign exemptions appear in mandatory clearing requirements, which would otherwise require them to post initial and variation margin on cleared trades, and in proposals requiring dealers to collect collateral on uncleared trades.

But there are exceptions to every rule, and some sovereign clients are now considering posting collateral on bilateral over-the-counter trades. The Cypriot, Danish and Latvian debt offices are all studying the issue, potentially bringing them in line with those already posting collateral: Hungary, Ireland, Portugal and Sweden. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB) is understood to be considering the merits of central clearing, and sent out a request for proposal to several banks offering client clearing in the third quarter of last year, according to three sources. That’s despite the fact it campaigned for an exemption from mandatory clearing requirements in the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (Emir).

For the most part, the main driving force for these sovereigns is higher costs – or anticipation of higher costs – on uncollateralised swap transactions. There are various factors causing this, but one of the most important is the realisation that the one-way credit support annex (CSA) favoured by sovereigns creates a huge funding burden for dealers.

These agreements require the dealer to post collateral when the market value of a trade is in the sovereign’s favour, but do not require the client to reciprocate when the situation is reversed. This poses real problems for any bank that has hedged with another dealer or has put the hedge through a clearing house – it would not receive any collateral when the original trade is in its favour, but would still have to post collateral on the offsetting position.

This may not have mattered so much pre-crisis, when funding was cheap and plentiful, but it’s a completely different story today – and the exposure is substantial. The total size of the funding obligation was $29 billion for five banks that provided figures to Risk in February last year (Risk February 2011, pages 18–22). A more recent survey, published last December by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Association for Financial Markets in Europe (Afme) and International Capital Market Association (ICMA), estimated dealer exposure to European sovereigns could total around $70 billion.

Having one-way CSAs can act as a severe funding strain on dealers, because your hedge to that trade will almost always be with an interbank counterparty, and this will be subject to a two-way CSA or will be cleared

“Having one-way CSAs can act as a severe funding strain on dealers, because your hedge to that trade will almost always be with an interbank counterparty, and this will be subject to a two-way CSA or will be cleared. You effectively have to fund the mark-to-market of your client when you are in-the-money on the trade,” says Nitin Gulabani, global head of foreign exchange, rates and credit at Standard Chartered in Singapore, and an Isda board member.

Capital charge

There are other implications arising from the refusal of sovereign clients to post collateral. In particular, banks will be required to comply with the credit value adjustment (CVA) capital charge under Basel III from 2013. A key input in the CVA capital calculation is the exposure to a counterparty – and, without collateral acting as a mitigant, the charge could be significantly higher than it would be on a trade backed by a two-way CSA.

In the absence of collateral, the only way a bank can hedge the capital charge is through the credit default swap (CDS) market. However, this creates issues of its own. Specifically, dealers warn it could create a negative feedback loop between CVA and CDS spreads – an increase in CVA would encourage dealers to buy more CDS protection, which could help push spreads wider, in turn increasing the CVA.

Banks already hedge their CVA exposures, so that dynamic exists to some extent at the moment, but dealers argue the new capital charge will increase demand for protection. There are also differences between current hedging practices and the CVA capital rules. Banks typically hedge CVA using a combination of credit and market risk hedges. However, market risk hedges are not recognised under the Basel III CVA rules – in fact, these positions would attract capital of their own.

That means any shift in interest rates or foreign exchange that results in the market value of the trade improving for the dealer – thereby increasing its CVA exposure – can only be mitigated by buying more CDS protection. What is more, sovereign clients tend to use derivatives in similar ways – to swap fixed rate into floating – meaning dealers tend to be positioned the same way, and could end up rushing to buy protection at the same time in response to a market move. That wouldn’t matter if the sovereign CDS market was liquid enough to absorb this demand – unfortunately, it isn’t. According to the Isda/Afme/ICMA paper, if dealers were to hedge their European sovereign exposures through the single-name CDS market, it could require as much as 50% of the entire open interest.

In theory, the ability to hedge through the CDS market means sovereign clients will not see the entire capital charge passed on to them, but they may be required to compensate the dealer for the cost of the CDS hedge – and European sovereign spreads have widened significantly since the onset of the eurozone sovereign debt crisis. If there are not enough sellers of protection to meet the demand for CVA hedges, these spreads could be pushed wider still, dealers say (Risk November 2011, pages 17–20).

Ultimately, the impact of the CVA capital charge on sovereigns may not be as severe as many predict – at least not in Europe. In a recent version of the fourth Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV), drawn up by the Council of the European Union in March, banks are not required to apply the CVA capital charge to trades conducted with European central banks and sovereign debt offices. This comes on top of the sovereign exemption from the mandatory clearing obligation and margin requirements for uncleared swaps under Emir.

The CVA exemption is not definite – it still has to be approved by the council, European Parliament and European Commission before it makes it into the final version of CRD IV. As such, some European sovereign debt offices want to see how this pans out before making any changes to their collateral policies.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Credit risk

US bank CROs see only ‘modest’ credit risk from tariffs

Risk Live North America: Lower margins are early sign of stress, but Ally, Citizens and Pinnacle confident on loan books

Credit risk management solutions 2024: market update and vendor landscape

A Chartis report outlining the view of the market and vendor landscape for credit risk management solutions in the trading and banking books

Finding the investment management ‘one analytics view’

This paper outlines the benefits accruing to buy-side practitioners on the back of generating a single analytics view of their risk and performance metrics across funds, regions and asset classes

Revolutionising liquidity management: harnessing operational intelligence for real‑time insights and risk mitigation

Pierre Gaudin, head of business development at ActiveViam, explains the importance of fast, in-memory data analysis functions in allowing firms to consistently provide senior decision-makers with actionable insights

Sec-lending haircuts and indemnification pricing

A pricing method for borrowed securities that includes haircut and indemnification is introduced

XVAs and counterparty credit risk for energy markets: addressing the challenges and unravelling complexity

In this webinar, a panel of quantitative researchers and risk practitioners from banks, energy firms and a software vendor discuss practical challenges in the modelling and risk management of XVAs and CCR in the energy markets, and how to overcome them.

Credit risk & modelling – Special report 2021

This Risk special report provides an insight on the challenges facing banks in measuring and mitigating credit risk in the current environment, and the strategies they are deploying to adapt to a more stringent regulatory approach.

The wild world of credit models

The Covid-19 pandemic has induced a kind of schizophrenia in loan-loss models. When the pandemic hit, banks overprovisioned for credit losses on the assumption that the economy would head south. But when government stimulus packages put wads of cash in…