A turning tide for two-way CSAs?

Preparing for two-way CSAs

But even if there is an exemption from the CVA capital charge, it doesn’t mean banks will stop hedging CVA exposures entirely – meaning hedging costs will filter through. The funding burden that exists through one-way CSA exposures will also remain, and these costs may well be passed on. As a result, several sovereign debt offices are making preparatory steps towards two-way CSAs now.

For instance, the Danish central bank, Danmarks Nationalbank, published a report in February confirming the costs of trading under a one-way CSA had risen since the financial crisis. This prompted its debt management arm to begin a study on the cost implications of moving to two-way collateral posting. It plans to publish its analysis by the end of the year.

“We are currently analysing bilateral collateralisation because we are well aware of the capital implications and liquidity obligations that our banking counterparts are facing with regard to one-way CSAs, and how these issues are likely to affect the cost of transacting swaps,” says Ove Sten Jensen, head of the government debt management department at Danmarks Nationalbank in Copenhagen.

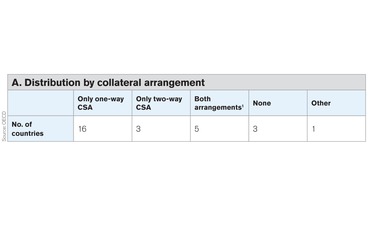

According to a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in November, just three sovereign debt management offices use two-way CSAs exclusively – although a few more use them alongside one-way agreements. That compares with 16 that only use one-way CSAs (see table A).

Two of those using two-way CSAs have adopted them over the past two years. Portugal’s Instituto de Gestão da Tesouraria e do Crédito Público made the change in July 2010 amid expectations that prices would increase for swaps under one-way CSAs (Risk August 2010, pages 24–26). The most recent conversion is Ireland’s National Treasury Management Agency (NTMA), which announced it had started posting collateral last year (Risk September 2011, page 8). Dealers say the NTMA’s hand was forced, as banks were reluctant to trade with it on an uncollateralised basis as the country moved closer to a European Union (EU)-International Monetary Fund bail-out.

This list is expected to grow, with the Latvian and Cypriot debt offices conducting similar analysis to Denmark. However, the speed of the conversion will depend on whether banks are passing on the full cost of the funding obligation and CVA hedge. The large dealers say they are incorporating these elements into their pricing now, but acknowledge these costs might be waived to win prestigious sovereign clients.

“The pressure to post collateral is definitely being applied to sovereigns, but the outcome of this pressure will depend on whether banks are actually reflecting the true costs in the price of the swap. Theoretically, the cost should be shared between the dealer and the client, but the split may differ between banks and counterparties,” says Gulabani at Standard Chartered.

Others agree, noting this can make it difficult for banks that are taking all these factors into account to compete. “There are still a number of banks not pricing in the true funding obligations on long-dated swaps with sovereigns, and this makes it tricky for banks that are pricing in the correct funding costs to compete. While only a small subset of banks is mispricing these trades, it’s still a problem that needs to be rectified,” says Tong Lee, global head of rates at UniCredit in London.

Beyond pricing, there are other issues that may delay the switch to two-way collateral posting. The Latvian debt management office, for instance, has asked Eurostat, the statistical office of the EU, whether the posting of collateral would have any impact on its debt levels.

“We have spoken to a number of our counterparties, and we know there are incentives for them to sign two-way CSAs. We have asked for differences in prices between uncollateralised swaps and trades that are bilaterally collateralised, and we found it would generally improve the pricing of the swap and the treatment would be more favourable. But it is not as straightforward as that. We have also made enquiries with Eurostat about how the posting and receiving of collateral would affect our liabilities. So we’re looking to cover all the bases before we make a decision,” says Girts Helmanis, director in the financial resources department at the Treasury of the Republic of Latvia in Riga.

As it stands, cash collateral posted to debt offices and other sovereign entities against derivatives counterparty exposures is technically required to be reported as a loan and included in each country’s debt statistics (Risk March 2011, page 26–28). The same applies if the sovereign had to raise funds in order to meet a collateral call – the debt statistics for the country would increase by that amount.

Others are also concerned about this point – the Cypriot Public Debt Management Office (PDMO), for example, acknowledges it may sign two-way CSAs, but is looking at how it will affect debt levels.

“We are infrequent users of swaps and have only transacted with local banks on an uncollateralised basis so far. But we are exploring the possibility of expanding our list of counterparties to include other European banks and, if we decide to do that, we anticipate having to sign two-way collateral agreements. So we will be examining exactly how posting and receiving collateral is treated from a public debt perspective,” says Phaedon Kalozois, director of finance and the head of the PDMO at the Cypriot Ministry of Finance in Nicosia.

Central counterparty clearing

Signing a two-way CSA is one way to avoid having funding and capital costs passed on by dealers. The other is to clear derivatives through central counterparties (CCPs). According to the OECD report, just one sovereign debt manager is using a CCP for interest rate swaps – believed to be the Riksgälden, the Swedish debt management office (Risk March 2011, page 9). Given the exemption written into Emir, others won’t be forced to follow suit, but some debt managers and central banks think it is a good idea.

“We already have two-way CSAs, and we are currently gathering information about central clearing and figuring out whether market forces are going to take us down this road. We are talking with our counterparties but, as yet, we haven’t felt compelled to decide to centrally clear, and we’re not sure how it would all work. But if, in theory, we were to centrally clear, it would actually benefit us from an operational perspective because we are currently having to deal with multiple collateral flows every day. Whereas, if we used one or two clearing members or joined a CCP directly, we would only have one or two collateral flows,” says Ondrej Stradal, head of foreign exchange reserves management at the Česká Národní Banka, the Czech national bank in Prague.

The ECB published a paper last November that outlines five standards for central banks that want to access central clearing, and is understood to have set up an internal working group to look into the issue, but declined to comment.

Ultimately, it comes down to costs. If banks pass the funding and capital charges on to sovereign clients, more will likely consider a change to central clearing or two-way collateralisation. As long as banks are willing to absorb these costs to win business, however, there is little incentive to change.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Credit risk

US bank CROs see only ‘modest’ credit risk from tariffs

Risk Live North America: Lower margins are early sign of stress, but Ally, Citizens and Pinnacle confident on loan books

Credit risk management solutions 2024: market update and vendor landscape

A Chartis report outlining the view of the market and vendor landscape for credit risk management solutions in the trading and banking books

Finding the investment management ‘one analytics view’

This paper outlines the benefits accruing to buy-side practitioners on the back of generating a single analytics view of their risk and performance metrics across funds, regions and asset classes

Revolutionising liquidity management: harnessing operational intelligence for real‑time insights and risk mitigation

Pierre Gaudin, head of business development at ActiveViam, explains the importance of fast, in-memory data analysis functions in allowing firms to consistently provide senior decision-makers with actionable insights

Sec-lending haircuts and indemnification pricing

A pricing method for borrowed securities that includes haircut and indemnification is introduced

XVAs and counterparty credit risk for energy markets: addressing the challenges and unravelling complexity

In this webinar, a panel of quantitative researchers and risk practitioners from banks, energy firms and a software vendor discuss practical challenges in the modelling and risk management of XVAs and CCR in the energy markets, and how to overcome them.

Credit risk & modelling – Special report 2021

This Risk special report provides an insight on the challenges facing banks in measuring and mitigating credit risk in the current environment, and the strategies they are deploying to adapt to a more stringent regulatory approach.

The wild world of credit models

The Covid-19 pandemic has induced a kind of schizophrenia in loan-loss models. When the pandemic hit, banks overprovisioned for credit losses on the assumption that the economy would head south. But when government stimulus packages put wads of cash in…