Leveraged ETFs dodge blame for volatility

The US Federal Reserve has warned that leveraged exchange-traded funds could pose a systemic risk through their rebalancing activities, but many exchange-traded fund providers think these claims are overblown

When the US Federal Reserve speaks, people tend to sit up and take notice. So when the central bank published a report warning about the systemic risks posed by leveraged and inverse exchange-traded funds (LETFs) earlier this year, it attracted plenty of attention in the media and among investors.

It is not the first time regulators have expressed concern about the possible systemic impact of the

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Exchange-traded products

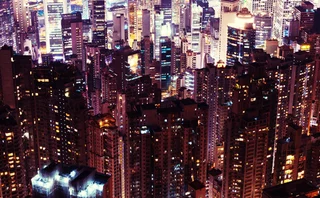

Realising the China opportunity

Webinar: HKEX

One size does not fit all: Smart beta explained

Sponsored feature: WisdomTree Europe

ETF Risk European Rankings 2015: ETF trading platform for institutional investors

Sponsored feature: Tradeweb

ETFs – Transforming the investment landscape in Asia

Sponsored survey analysis: Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management

Flood of oil ETF investors reshaping market, analysts say

'Massive' inflows cushioned oil price drop in early 2015, but could easily reverse

Currency-hedged ETF surge prompts hedging concerns

Eurozone QE programme prompts wave of investor interest

Currency-hedged ETF inflows boom

Investor interest sparks race to construct new products

Shanghai ETF option volatility spikes on China market fears

A crackdown on margin financing strengthens bearish sentiment