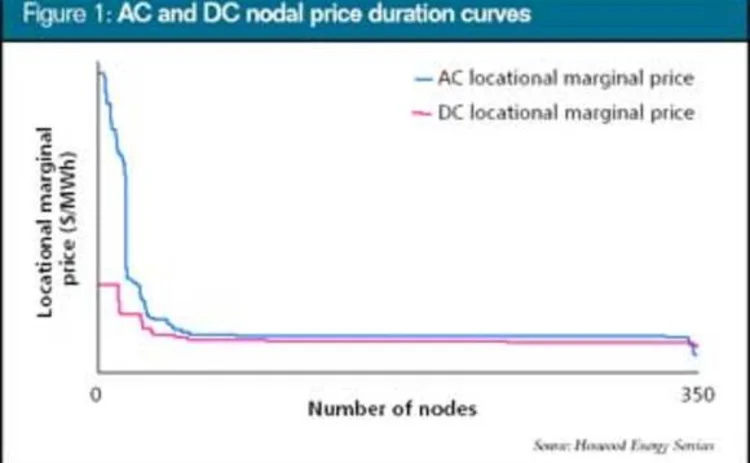

The LMP supermodel

With Ferc’s standard market design (SMD) seeking a shift from zonal power pricing to nodal pricing, the concept of locational marginal pricing (LMP) has become a key policy issue. Henwood Energy’s Vikram Janardhan proposes 10 key modelling features to look for in an analytical tool that can simulate LMPs and SMD markets

The US electricity market is fast becoming intensely competitive. On March 15, 2002, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (Ferc) issued Order 2000 to advance the formation of regional transmission organisations (RTOs) and further develop wholesale competition in the power utility sector.

Ferc’s aim is to improve certainty in market rules across RTO geographies, streamline

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Technology

What is driving the ALM resurgence? Key differentiators and core analytics

The drivers and characteristics of a modern ALM framework or platform

Are EU banks buying cloud from Lidl’s middle aisle?

As European banks seek to diversify from US cloud hyperscalers, a supermarket group is becoming an unlikely new supplier

Inside the company that helped build China’s equity options market

Fintech firm Bachelier Technology on the challenges of creating a trading platform for China’s unique OTC derivatives market

AI ‘lab’ or no, banks triangulate towards a common approach

Survey shows split between firms with and without centralised R&D. In practice, many pursue hybrid path

Everything, everywhere: 15 AI use cases in play, all at once

Research is top AI use case, best execution bottom; no use is universal, and none shunned, says survey

FX options: rising activity puts post-trade in focus

A surge in electronic FX options trading is among the factors fuelling demand for efficiencies across the entire trade lifecycle

Dismantling the zeal and the hype: the real GenAI use cases in risk management

Chartis explores the advantages and drawbacks of GenAI applications in risk management – firmly within the well-established and continuously evolving AI landscape

Chartis RiskTech100® 2024

The latest iteration of the Chartis RiskTech100®, a comprehensive independent study of the world’s major players in risk and compliance technology, is acknowledged as the go-to for clear, accurate analysis of the risk technology marketplace. With its…