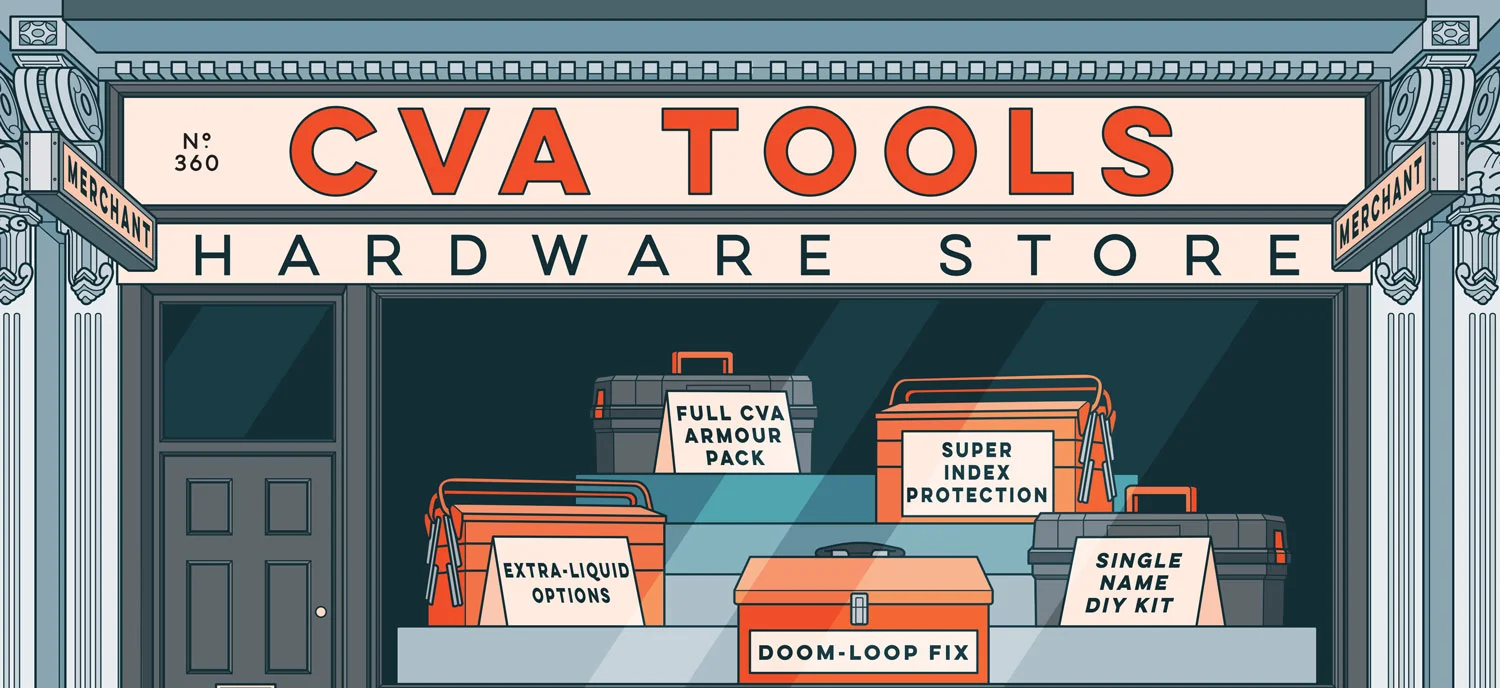

CVA desks arm themselves for the next crisis

March’s volatility forces dealers to fine-tune hedging strategies

April is said to be the cruellest month. But for one European bank’s credit valuation adjustment desk, the pain came a month earlier.

The bank had entered into a series of interest rate swaps and foreign exchange derivatives with a group of South American oil companies. The trades moved firmly in the bank’s favour after central banks cut policy rates in March, but the subsequent collapse in oil

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Markets

Esma to issue guidance on active account reporting

Briefing and Q&A aims to clarify how firms should report data ahead of RTS adoption

Forex looks to flip the (stable)coin

Friction-free foreign exchange is the prize offered by stablecoins such as Tether and USDC. But the prize remains elusive

Market warns BoE against blanket mandatory gilt repo clearing

Official says proposals receiving push-back on one-size-fits-all approach and limited netting benefits

Banks eye cost cuts ahead of RateStream Treasuries push

FX SpotStream’s move into rates seen as both fee-saver and potential boost to streaming execution

Real money investors cash in as dispersion nears record levels

Implied spreads were elevated to start 2026. Realised levels have been “almost unprecedented”

JP Morgan gives corporates an FX blockchain boost

Kinexys digital platform speeds cross-currency, cross-entity client payments

China eases cross-border grip in new derivatives rules

Lawyers hail return to a “more orthodox territorial approach” to regulating the market

Fannie, Freddie mortgage buying unlikely to drive rates

Adding $200 billion of MBSs in a $9 trillion market won’t revive old hedging footprint