All clear? Structural shifts add to repo madness

Many things contributed to 10% repo, among them a FICC programme and a surge in overnight funding

Need to know

- When the overnight repo rate shot to 10% on September 17, it was largely blamed on a Treasury settlement and a corporate tax payment falling the day before.

- But the ground has been shifting under the market with the growth of the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation’s sponsored repo programme and a big move to overnight funding, led by hedge funds.

- Sponsored repo has resulted in large concentrations of cash at a handful of banks, making the repo market more fragile.

- To calm the market, the Federal Reserve has been lavishing it with billions of dollars in overnight and term operations, as well as Treasury bill purchases.

- More hedge funds have joined the FICC’s sponsored repo programme since September 17, while some have started borrowing directly from MMFs.

On September 17, rates on overnight repo, backed by the bedrock pledge of US Treasuries, suddenly lurched to 10% from typically low single digits in a session that turned into a feral lunge for cash.

In some corners of the market, traders pleaded for cash; in others, people holding it gloated.

“At dinner and drinks that night, I did hear people bragging that they made 400 basis points selling into overnight repo,” says the head of a broker-dealer in New York.

One hedge fund manager said he was willing to pay three times his usual rate to borrow cash – a bank salesperson just laughed over the phone.

To some observers, the scuffle recalled last New Year’s Eve, when rates suddenly flowered higher – not this high – delivering a shock just hours before the ritual end-of-year carousing. To others, September 17 carried intimations of the demise of Lehman Brothers, a watershed in financial history.

But this wasn’t a Lehman-type event. Nor was it quarter-end, when funding can be tight.

So, what caused the US Treasury repo market to seize up on September 17? (See box: Tuesday, September 17.)

The common explanation is that a $148.6 billion cash call – tax payments and a Treasury auction settlement the previous day – yanked about 10% of the $1.2 trillion market’s daily liquidity, leading to a minor panic.

But some repo traders find that too pat. They say it ignores quiet, tectonic shifts in the market going back years that have been making themselves felt more and more.

Among them: excess reserves at banks, once a source of cash in repo, have been falling away following a shift in monetary policy. Less well-known is a move by primary dealers, broker-dealers and hedge funds towards overnight funding that has added pressure.

At dinner and drinks that night, I did hear people bragging that they made 400 basis points selling into overnight repo

Head of a broker-dealer in New York

And the sponsored repo programme at the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), originally designed to ease pressure on bank balance sheets and smooth the moving of money, may actually have fostered conditions that made the repo market more fragile, concentrating business at a handful of banks and clogging the process.

Risk.net spoke to 28 repo market experts, among them global systemically important banks (G-Sibs), money market funds, broker-dealers, hedge funds and others. They say the mesh of factors around the repo market today will continue to exaggerate rate moves going forward. But the reasons for the day’s jagged movements are still hard to disentangle.

“Anybody that thinks they can tell you they know the reasons why is being relatively untruthful,” says the head of the financing desk at a primary dealer.

The FICC of it

Most of the crags ahead of September 17 were known in advance: a $70.6 billion corporate tax payment and a $78 billion US Treasury settlement, both the day before. Also known was that banks had fewer excess reserves to put into the repo market.

But all of this was predictable. Indeed, many think the amount of cash in the market that day was only slightly less than usual. Cash supply into the FICC’s sponsored repo was down only $20 billion on September 17 – similar to the decline in the tri-party market – not an inconsiderable amount but given the US Treasury repo market is north of $1.2 trillion a day, not enough to cause the gyrations seen.

Others say that cash eventually did trickle into the market on September 17, but too late to keep rates from ratcheting higher.

So what happened?

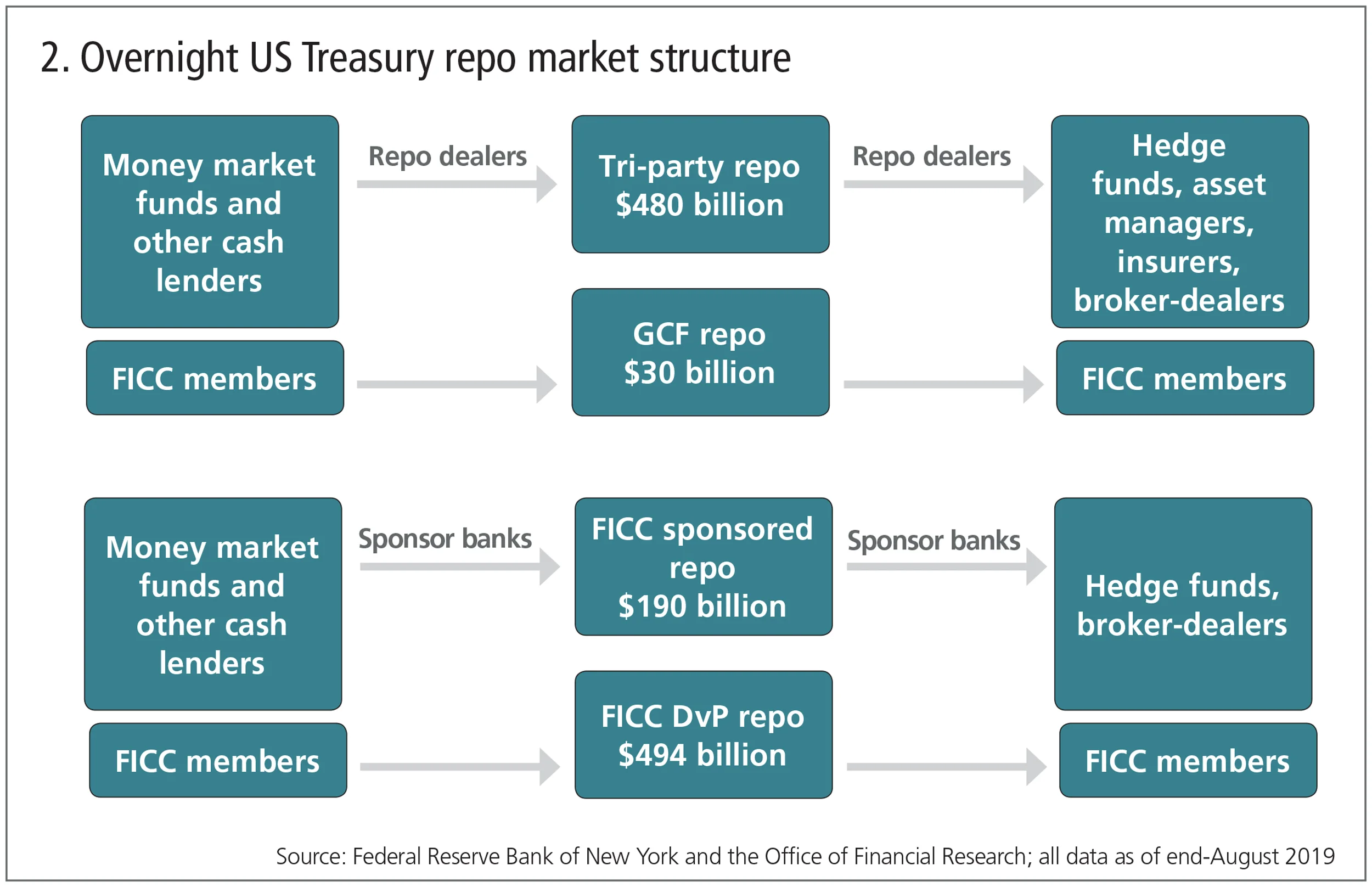

The answers are many, but some of them lead to the FICC’s sponsored repo programme, an effort designed to get repo cleared and more cash into play via ‘sponsor banks’ that would stand between lenders (largely money market funds) and borrowers (broker-dealers, hedge funds and others). Despite its worthy intentions, the programme has had unintended consequences, among them, bottlenecks that may have choked rates higher – and this despite the fact that the vast majority of repo still occurs outside the programme.

But in the convolutions of the past year, the programme has produced one clear winner – the FICC itself, which now pulls in about a quarter of repo loans made by money market funds – from virtually nothing at the beginning of 2018 – through its clearing baleen.

Started in 2005, sponsored repo at first was limited to a small pool of investors and failed to gain much traction. But in 2017, the FICC revised its criteria, allowing qualified institutional investors other than just registered investment companies to participate in the service. That opened the door to money market funds.

Tempted by the attractive rates banks offered, the funds came calling. At first, it was just Federated Investors and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, but eventually others came, too, like BlackRock, JP Morgan Asset Management and Fidelity Investments.

So attractive was the set-up that within just two years the FICC had ballooned into the biggest counterparty for money market fund cash. According to the Treasury’s Office of Financial Research (OFR), the FICC was counterparty to $190 billion in money market fund trades at the end of August – 24% of all volume at money market funds, up from a mere 2.3% two years ago. This dropped to $170 billion, or 22% of all money market lending, at the end of September.

The sponsored repo programme also picked up steam as hedge funds – collateral providers – started to come on board as well. Sponsor banks were especially happy – the programme enabled them to ramp up repo activity without consuming precious balance sheet on non-cleared business.

At present, the FICC has eight such sponsors: Bank of New York Mellon, ED&F Man, JP Morgan Bank North America, JP Morgan Securities, Mizuho Securities, Morgan Stanley, Palafox Trading and State Street, serving 1,750 firms among them. Twelve more sponsors have been approved.

But the reality on the ground looks different: State Street and BNY Mellon together sponsor in virtually all the cash and collateral providers. According to JP Morgan research, the two sponsor in 84% of money market funds to the FICC. JP Morgan Securities sponsors in four BlackRock money funds, accounting for the remaining 16%, while others sponsor in a handful of collateral providers, hedge funds like Point72, Brevan Howard, Mariner Investment Group and Citadel.

Until April, buy-side firms could only trade with their sponsoring banks and only banks could be sponsors. Since then, however, buy-siders can trade with counterparties their sponsor has approved, and those sponsors can now be broker-dealers, foreign banks or prime brokers.

Even so, Risk.net understands that almost all business continues to be done with sponsoring banks, instead of through any of the new, approved counterparties.

Non-bank broker-dealers do not have the same deep, extensive relationships with money market funds that banks do, so they rely on those sponsoring banks to pass cash into the interdealer markets.

“Back when banks were limited by balance sheet restrictions, large MMF [money market fund] investors would be forced to transact with many different counterparties. Now, they just give all their cash to banks via the sponsorship programme,” says a repo trader at a broker-dealer and a member of the FICC.

Instead of multiple firms competing in the interdealer market to invest cash rehypothecated from MMFs, now a few big banks control the market

A repo trader at a broker-dealer and a member of the FICC

“This creates concentration and reduces competition, and instead of multiple firms competing in the interdealer market to invest cash rehypothecated from MMFs, now a few big banks control the market,” the trader says.

Money market funds have a more mixed view of this. Deborah Cunningham, chief investment officer at Federated Investors, which runs money market funds, notes that the funds are legally bound by concentration limits, which force them to use a variety of counterparties – not just sponsoring banks.

“I disagree with the assumption that FICC is making things more concentrated,” she says. “If we had unlimited capacity with those sponsors, then I would say, maybe. But we are very diversified and specified with how much we can have with one of those counterparts.”

But Robert Sabatino, global head of liquidity investments at UBS Asset Management, another shop with money market funds, does think the concentration argument has some merit.

“We’ve seen an increase in FICC repo by MMFs, so it does likely mean that direct access to some MMFs has decreased for some of the banks,” he says.

Broker-dealers have grown wary of the stranglehold a small number of banks have on the market, so much so that some have tried to widen their funding sources, using mid-tier banks and the Federal Home Loan Banks system to put some distance between themselves and the FICC.

The broker-dealer in New York, for example, gets two-thirds of its cash outside the FICC’s embrace. “Thank God for that – otherwise that Tuesday would have been substantially uglier,” says the head of the firm.

The FICC declined to comment for this article.

The concentration of cash in a few hands may loosen up some once the FICC’s April opening has time to take root. But for now, the situation is precarious. According to OFR data, the top five counterparties to money market funds (excluding the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo programme) accounted for 45% of the market in September of last year, but 12 months later now account for 54%. JP Morgan alone has seen its market share lurch higher – from 2.39% to 10.18% in that period, not including its share of sponsored repo.

I’m not sure any of this was a true squeeze to start with, but once volatility kicked in, there was a squeeze for sure

Repo veteran who has a relationship with one of the sponsors

The sponsored membership programme has “concentrated cash in fewer hands. This reduces competition and makes spikes more likely to be more severe,” says the repo trader at the broker-dealer.

On September 17, these narrow channels of business played out in an odd way. Offers on the broker screens typically are done in increments of $1 billion to $2 billion; on that day, however, those sizes dropped to $250 million apiece as cash lenders looked to test how high rates might actually go, observers said.

“We know they [banks] have cash, but it’s always at what price do they have the cash,” says a repo veteran who has a relationship with one of the sponsors. “I’m not sure any of this was a true squeeze to start with, but once volatility kicked in, there was a squeeze for sure.”

Yet another factor, though, was the growing taste for overnight funding, which devolved into a frantic scramble for cash on the day. At present, the overwhelming majority of FICC sponsored repo is done overnight, in part because banks have to guarantee the performance of any and all of their counterparties to the clearing house. The FICC is understood to be working on a liquidation rule governing sponsored members with the aim of encouraging banks to do more term repo.

But on September 17, dealers, hedge funds and others were heavily tilted towards overnight funding.

The overnight life

For an array of reasons, overnight funding has stormed repo. Whereas once overnight cash existed in something of a balance with term funding, it is now the preferred horizon on both the borrowing and lending sides of repo.

According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, overnight trades accounted for 73% of repo transactions as of September 18.

On the borrower side, the move to overnight funding was led by hedge funds and other levered entities running basis trades between US Treasuries – an increasingly popular strategy that exacerbated the repo rate increase on September 17.

“The theme of levered counterparties buying a bond, funding overnight versus term, allowed for a substantial – and arguably too much – overnight funding on leveraged positions,” says the head of the financing desk at the primary dealer.

Data from the US Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission illustrates the extent to which hedge funds have piled into the fixed income arbitrage play between US Treasuries and futures in recent years.

The latest SEC aggregate data on hedge fund exposures shows a big jump in US government bond buying to $1.8 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2018, from $1.1 trillion in the first quarter of 2017.

CFTC data shows the other part of the trade: a surge in short US Treasury bond futures positions that began at the end of last year and continued even as open interest in long positions – which had grown at a similar pace – fell away during the third quarter. Since December 2018, open interest in short positions is up 284%.

The trade has caught on as some ‘real-money’ accounts have ditched US Treasuries for corporate bonds with higher yields. Pension funds and insurance firms have also opted to source duration via futures, a practice that is making futures artificially rich and Treasuries artificially cheap, says the head of repo at a second primary dealer.

“The relative-value guys are facilitating that role,” the repo head says. “They’re selling futures that are demanded by real-money investors who are sourcing their duration in futures so they can then go and buy credit products because they earn a higher yield on their portfolio.”

The head of the financing desk at the first primary dealer says most relative-value traders would enter into a position if they can make at least 15bp with term funding. But, if they could pick up another 10bp by funding overnight, why not?

“So many levered players did that – they funded overnight because they thought they could always fund overnight,” says the financing head.

The reason for the migration to overnight funding is term premium – even with the volatility in the market. A typical spread between overnight and term repo would be 4–5bp, says the veteran repo trader, but that spread has widened to 10–15bp.

“The holders of cash are being a lot more greedy than they used to be,” the trader says.

Fixed income arbitrage trades had been earning anywhere between 2% and 5% a year – a reliable pittance in the hedge fund world. But the amount of crowding in the trade and the leverage taken on “100% would have exacerbated the repo volatility,” says the repo head at the primary dealer.

Experts estimate a number of funds were forced out of some positions and others took losses of 1% to 2% on the strategy the week repo spiked.

But it wasn’t just hedge funds looking to squeeze basis points that were driving the overnight money. On the lender side, the trend was also taking root. In the money market fund arena, a change in rules in 2016 forced the funds to become more conservative. As a result, cash poured into government money funds – many of which invest in the repo market – and those funds began shortening their average maturities, says Joseph Markowksi, a portfolio manager in BlackRock's cash management group.

SEC data reflects this: since 2016, government-only money funds have lopped their weighted average maturity by about 15 days. When those funds held back some cash at the start of trade on September 17, this only exacerbated things further.

“You have to consider the risk-averse nature of the industry,” Markowski says, noting that money market funds have to be able to pay redemption requests.

“When you run a cash pool that allows for daily redemptions of unlimited size and you see stress in the marketplace, I think the intuition is to shore up liquidity on the margin,” he says. “I think that speaks a little bit to a concentration of cash in the tri-party repo market.”

Laurie Brignac, head of global liquidity at Invesco, which offers money market funds, paints a similar picture of September 17.

“You have to leave a cushion open in the morning, and unfortunately for counterparties looking for funding, we had to hold back some of our funding because we weren’t sure how much of redemptions or purchases we would see in our funds,” she says.

The concentration in overnight funding had been building for a while, and, along with other factors, was complicit in the mayhem of September 17 (see box: Tuesday, September 17).

“I think that sowed the seeds for what was a relatively fragile funding,” says the head of the financing desk at the first primary dealer.

A velvet rope

In essence, the Fed now bails out the repo market every day.

To defend its Fed funds rate, which flicked as high as 4% on September 17, the New York Fed pumped $75 billion in overnight money into the market, which it upped to $100 billion as quarter-end loomed and then again to $120 billion. Besides the overnight cash, the Fed’s open market trading desk began ongoing term operations of $35 billion, which it subsequently raised to $45 billion. The Fed will conduct both the overnight and term operations at least through January next year.

The Fed also said it would start purchasing $60 billion worth of Treasury bills from October 15 through the second quarter of 2020 to help ease the stress on bank reserve balances, hopefully soothing banks enough to coax them back into the market and stem the volatility in money markets.

But despite the flood of liquidity, the velvet rope between those that have cash and those who need it remains. Primary dealers can borrow directly from the Fed, but cash has struggled to reach other corners of the market.

On September 30 – the end of the third quarter – the secured overnight financing rate, an average of US repo rates, jumped 53bp from the previous day. The difference between the first and 99th percentiles was 120bp – from a typical median spread of 18bp.

“This is the spread between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’,” says the repo trader at a FICC-member broker-dealer. The median spread has been widening lately, he adds. “When this spread is elevated, it means cash isn’t filtering through to the broader market.”

On October 15, another corporate tax payment day, the spread moved up to 50bp before dropping to 30bp the day after.

The elevated spreads have prompted more cash borrowers – including hedge funds involved in fixed income arbitrage, such as MKP Capital Management, Rimrock Capital Management and Lighthouse Investment Partners – to get themselves sponsored into the FICC. Meanwhile, hedge funds Millennium Management and Garda Capital have started borrowing directly from Federated Investors, with Barclays guaranteeing the trades.

For those outside FICC, the situation remains precarious. Some believe they might be able to calibrate their trading on sensitive days such as New Year’s Eve 2018 or September 17 with its tax and Treasury whammy. But in the event of, say, a shock, the next ride could be even wilder. Many are already wondering with some trepidation how this New Year’s Eve will play out.

“What I’m deeply concerned about is now in the fourth quarter, there will be a group of banks that care more about their balance sheet now than they did in the third quarter,” says the head of repo at the primary dealer. “Fourth-quarter balance sheet is going to be more challenged.”

In a note, Niall Coffey, chief executive of Avoca Global Advisors – formerly the chief forex dealer at the New York Fed – wrote that “further volatility and more fractious market stress in US repo markets will occur without regulatory relief, and we are concerned that demand for US Treasury debt could fall in the coming months.” The post-financial crisis regulatory regime is “a source of significant systemic liquidity risk,” he said, and gave high odds “that the current market cycle would ultimately end with a 1987 style crash”.

Or the end of this year might be another September 17, with the cash-hungry trying to get past the cash bouncers.

A short-term rates trader at a Japanese bank recalled one cash borrower who, just a week earlier, had quibbled over a few basis points, but that day found himself iced out by his bank as rates backed up.

“Sorry, mate. Can’t help you,” he was told.

Tuesday, September 17

The melee of Tuesday, September 17 was brewing quietly in the unease of the previous day.

“The blood was in the water on the Monday afternoon,” says a US rates strategist in New York.

Corporations had begun pulling their cash out of money market funds the previous Friday to meet tax payments on the Monday – cash that typically would have gone into the repo market. In total, around $34 billion was withdrawn from Friday, September 13 to that Monday (the total tax payment due was $70.6 billion).

Still, the amount involved was nothing out of the ordinary – it was similar to those in previous tax years, according to Deborah Cunningham, chief investment officer at Federated Investors.

September 16, however, was also settlement day for the previous week’s $78 billion Treasury auction of three- and 10-year notes and 30-year bonds. Paying for those drained more cash from the market.

Having both things – taxes and Treasuries – land the same day gave some traders a bad feeling. Demand for cash had already pushed rates up 23 basis points on Monday versus Friday, as the volume of forward trades – which settle the next day – doubled. Participants grew cagier.

Joseph Markowski, a portfolio manager in BlackRock's cash management group, says counterparties were asking for late-afternoon cash – a strange request, given that over three-quarters of funding is done first thing in the morning. The rates being offered on Monday were also a surprise, with highs already at 4.6%, more than double the normal rate.

Those needing cash started to sense something was off.

“There were enough people that didn’t feel tax payments and Treasury settlements were the right answers, so they started on Monday funding themselves for Tuesday,” says the head of the financing desk at a primary dealer. “Someone took some chips off the table.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, too, felt something was off. Coming in Tuesday, it announced it would run a repo operation with primary dealers for up to $75 billion starting at 9:30am Eastern Time to help control its Fed funds rate – its policy target rate – which had hit the top of its 2.25% range on Monday.

To most of the market, the Fed was caught off guard and its response looked naive – the action in funding begins as early as 7am, and by 9:30 would be largely over. But in any case, the Fed didn’t get into the market at 9:30 – “technical difficulties” forced it to delay the operation by nearly half an hour to 9:55.

And despite its intervention, the Fed funds rate breached the top of its range on Tuesday, hitting 2.3%.

Making matters worse on September 17, money market funds came in cautiously that morning and did not put all their cash to work until later in the day, leading to an even bigger scramble.

This resulted in the secured overnight financing rate averaging 5.25% for the day – usually it’s below 2.25% – and in one cash borrower taking in money for that spectacular 10% for which September 17 will be remembered.

“I’ve been doing this for 21 years and I’ve never seen anything like this happen,” says one head of group Treasury assets and liabilities at a bank in New York.

The falling away of excess reserves

The machinery of the repo market is simple enough: money market funds lend cash to banks and broker-dealers, which then lend it on to hedge funds and other non-banks in exchange for collateral, in this case, US Treasuries. Generally, the market is a lagoon of placidity.

But well before September 17, one font of cash to the lagoon was drying up: excess reserves at banks, once a cash pot to overnight repo.

Banks blame post-crisis regulations: the Dodd-Frank Act and Federal Reserve’s stress tests. But US fiscal policy, with its gushing Treasury issuance, and even the recently halted quantitative tightening, have played a role, too.

The cause most maligned by banks is Dodd-Frank, which requires them to hold a basket of high-quality liquid assets that, if needed, could be sold during a 30-day stress scenario to meet the liquidity coverage ratio.

That’s money that in a pinch could have been rushed to a market in distress. Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JP Morgan, said on the bank’s third-quarter earnings call in mid-October that while it could have come into the market and provided cash on that last day of 2018, September 17 was out of the question – despite having $120 billion sitting in excess reserves.

“That cash, we believe, is required under resolution and recovery and liquidity stress-testing, and therefore we could not redeploy it in the repo market – which we would have been happy to do,” he said.

But the free-spending US government has not helped repo liquidity either. Treasury supply increased $378 billion from August through September after the US Senate passed a two-year budget, according to data from JP Morgan, with 45% of that Treasury bills. The issuance jacked the US Treasury’s general account to a recent high of $378 billion on October 23 from a recent low of $125 billion on August 21, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

And primary dealers had to buy those Treasuries.

“If the Treasury general account is increased, that’s billions of dollars coming off banks’ excess reserves pile where the treasurer might have invested that money in the repo market instead,” explains EG Fisher, co-chief investment officer and head of liquid market strategies at the Mariner Investment Group.

Quantitative tightening, the wind-down of the Fed’s trillion-dollar rescue of the financial system, also played a role before it was ended in August. Bank excess reserves, which had been on a gentle downward slope, started falling faster since the rollback began in October 2017. Beginning in November 2017, they dropped from $2.2 trillion to $1.3 trillion, according to the St Louis Fed.

According to Bank of America research, Citi, Bank of America, JP Morgan and Wells Fargo made up just under $400 billion of those excess reserves – a drop from more than $700 billion in 2017. This, too, was due to quantitative tightening.

Rate jolts have become increasingly common since 2015 when banks – particularly French banks – subject to leverage rules that record their exposure at quarter-end, simply close shop and make their balance sheet unavailable to the market. Rates have bounced higher at those points, but the moves are becoming more extreme.

Take the end of 2018. On the last day of the year, the general collateral rate hit 7.25% intraday, closing at 4%, up 107bp for the day – an intraday jump not seen since the worst of the financial crisis. This was blamed on the Fed’s risk-based capital surcharge for G-Sibs, which came into force in 2016. As a result, large US banks typically reduce trading on the last day of the year, when regulators take a snapshot of their books to calculate next year’s surcharge.

Banks complain that other Fed rules hinder their ability to lend cash: for instance, the Comprehensive Liquidity Analysis and Review, an annual test designed to “evaluate the liquidity position and liquidity risk management practices” of the largest banks and non-banks.

The Fed has known about the draining away of excess reserves from repo for a while. In April, Lorie Logan, senior vice-president in the markets group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, said regulators have been aware that “internal liquidity stress tests and meeting intraday payment flows” were big impacts on reserve demand, and that the Fed would need to “conduct outright purchases of Treasury securities” to help restore the supply of reserves.

On September 17, it started doing just that. The Fed is now putting $120 billion into the market on an overnight basis, and doing term operations of $45 billion, both through January. It is also buying $60 billion worth of Treasury bills per month through the second quarter of 2020.

Additional reporting by Louie Woodall

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Markets

How investment firms are innovating with quantum technology

Banks and asset managers should be proactive in adopting quantum-safe strategies

Banks hope new axe platform will cut bond trading costs

Dealer-backed TP Icap venture aims to disrupt dominant trio of Bloomberg, MarketAxess and Tradeweb

The future of fixed income

Apac investors’ use of fixed income products, the fast-track evolution of the UBS fixed income proposition and the innovations likely to be seen by 2030

Unlocking opportunities in the SRT boom

Exploring the opportunities emerging in SRTs, also considering broader SRT developments and structural innovations

Franklin Templeton dethrones MSIM as top FX options user

Counterparty Radar: MSIM continued to cut RMB positions in Q3, while Franklin Templeton increased G10 trades

HSBC loses FX forwards market share with EU funds

Counterparty Radar: UK bank reported 6% drop in notional volumes with Ucits funds in H2 last year

Franklin Templeton steps back into FX options

Former biggest user of the instrument among US mutual funds returns with $7.6bn of USD/JPY strategies

Equity vol convexity selling gains momentum

Risky hedging strategy is attracting interest but can investors learn from past convexity blow-ups?