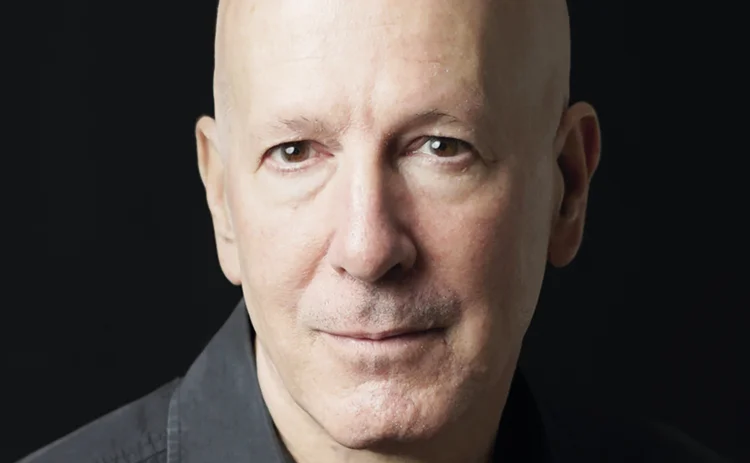

Bookstaber: past performance is no guide to future risks

Veteran risk chief says trading gains in the wake of LTCM’s demise forged love of agent-based modelling

Rick Bookstaber’s CV reads like a Who’s Who of Wall Street, stuffed with spells at its most storied institutions and stints working with some of its most colourful personalities.

Bookstaber, now in his 70s and still looking to stretch the industry’s horizons on approaches to risk modelling, was the first formal head of risk at Morgan Stanley, where he had a ringside seat for Black Monday. Next

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Risk management

Cyber insurance premiums dropped unexpectedly in 2025

Competition among carriers drives down premiums, despite increasing frequency and severity of attacks

Op risk data: Kaiser will helm half-billion-dollar payout for faking illness

Also: Loan collusion clobbers South Korean banks; AML fails at Saxo Bank and Santander. Data by ORX News

Market doesn’t share FSB concerns over basis trade

Industry warns tougher haircut regulation could restrict market capacity as debt issuance rises

CGB repo clearing is coming to Hong Kong … but not yet

Market wants at least five years to build infrastructure before regulators consider mandate

Rethinking model validation for GenAI governance

A US model risk leader outlines how banks can recalibrate existing supervisory standards

FCMs warn of regulatory gaps in crypto clearing

CFTC request for comment uncovers concerns over customer protection and unchecked advertising

UK clearing houses face tougher capital regime than EU peers

Ice resists BoE plan to move second skin in the game higher up capital stack, but members approve

The changing shape of variation margin collateral

Financial firms are open to using a wider variety of collateral when posting VM on uncleared derivatives, but concerns are slowing efforts to use more non-cash alternatives