Journal of Operational Risk

ISSN:

1755-2710 (online)

Editor-in-chief: Marcelo Cruz

The future of risk and insurability in the era of systemic disruption, unpredictability and artificial intelligence

Need to know

- Risk and uncertainty are fundamentally distinct; not all uncertainty is quantifiable.

- Deep uncertainty is driven by complexity, unknowability, and interdependent variables.

- Unprecedented events are becoming more frequent, challenging legacy risk models.

- Adaptive anticipatory frameworks are required for systemic disruption and unpredictability.

Abstract

In an era defined by systemic disruption, radical unpredictability and the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence, the classical distinction between risk and uncertainty, first articulated by Frank Knight and John Maynard Keynes, demands urgent reexamination. While traditional risk is measurable through probabilistic models, deep uncertainty involves unknowable probabilities and indeterminate outcomes that increasingly defy legacy risk frameworks. This paper explores how the rising frequency of high-impact shocks – technological, geopolitical, financial and epidemiological – exposes the fragility of conventional risk management approaches. It argues for a paradigm shift, from viewing disruption as episodic to understanding it as systemic, whereby interdependent stressors interact to produce cascading, nonlinear impacts. To address this complexity, we propose the antifragile, anticipatory and agility (AAA) framework as a novel approach for uncertainty management. Drawing on insights from complexity science, strategic foresight and adaptive resilience, the framework emphasizes imagination over prediction and prioritizes managing outcome amplitude over probability. By cultivating organizational shock absorbers and dynamic responsiveness, the AAA framework enables stakeholders to navigate open-ended volatility, build adaptive capability for decision-making under deep uncertainty and seize emergent opportunities across multiple plausible futures. This has critical implications for risk intelligence, insurability and policy design in increasingly volatile and complex environments.

Introduction

1 From risks to structural uncertainties

In 1921, the economist Frank Knight drew a foundational distinction between “risk” and “uncertainty”. According to Knight (1921), risk pertains to situations in which “the distribution of the outcome in a group of instances is known”. In contrast, uncertainty arises in contexts that are, to a significant extent, unique, making it difficult or impossible to assign probabilities to potential outcomes: “Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from which it has never been properly separated…. There is a fundamental distinction between the reward for taking a known risk and that for assuming a risk whose value itself is not known” (Knight 1921).

Around the same time, John Maynard Keynes similarly questioned the reliability of probabilistic reasoning in his Treatise on Probability (Keynes 1921). Both Knight and Keynes were responding to a growing realization in early twentieth-century thought: not all future events are foreseeable, and not all uncertainty can be reduced to quantifiable risk.

A century later, these insights have returned with renewed urgency. In Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers, John Kay and Mervyn King argue that in many modern contexts – particularly in finance, policy and technology – we face deep epistemic constraints (Kay and King 2020). Not only are probabilities unknowable, but the full range of possible outcomes may be fundamentally indeterminate: “Radical uncertainty cannot be described in the probabilistic terms applicable to a game of chance. It is not just that we do not know what will happen. We often do not even know the kinds of things that might happen.” (Kay and King (2020))

According to Knight, risk pertains to situations in which outcomes can be assigned numerical probabilities, thereby enabling calculation and pricing. By contrast, when such probabilistic specification is not feasible, the situation is characterized as uncertainty. This distinction necessitates a corresponding shift in analytical approach, from probabilistic modeling to alternative frameworks capable of addressing even deeper degrees of uncertainty (eg, systemic, nonlinear and emergent).

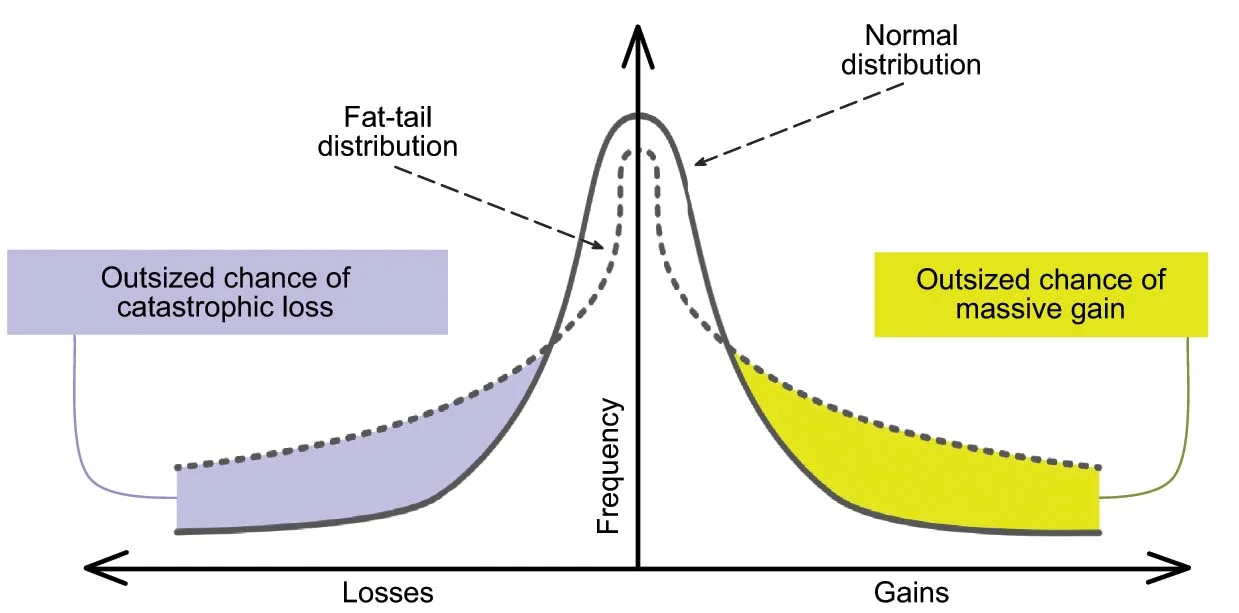

While risk management involves identifying, assessing, mitigating and adapting to risks, particular attention is needed for low-likelihood, high-impact events: so-called fat-tail risks (Taleb 2016). Future-focused risk intelligence should emphasize proactive strategies designed to anticipate and respond to the full spectrum of risks, ranging from frequent, predictable linear risks to rare, asymmetric events that could be catastrophic yet are often underweighted due to their low probability. These inherently nonlinear, asymmetric risks underscore the limitations of relying on probabilistic models when seeking to create certainty or to predict the unpredictable (Taleb 2016).

As introduced by Crichton (1999), risk can be conceptualized as a triangle, with hazard, exposure and vulnerability as the three sides. In Crichton’s “risk triangle”, the hazard represents the phenomenon that can cause the loss; the exposure is the asset, people or systems that could be affected by the hazard; and the vulnerability is the susceptibility of that exposure to suffer harm. Risk exists when all three components are present, and reducing any one of them decreases the overall risk. Thus, risk inherently involves the possibility of harm or loss resulting from the interaction of these three factors. The well-documented principle of loss aversion (Tversky and Kahneman 1992) illustrates that individuals tend to weigh losses more heavily than commensurate gains in their decision-making processes. This implies that the subjective impact of experiencing a loss is greater than the positive effect associated with an equivalent gain.

However, while risk management teams typically focus on mitigating the adverse outcomes of uncertainty, that uncertainty does not necessarily imply negative consequences. The challenge for today’s investment, finance and insurance sectors is to operate in environments that resemble genuine Knightian uncertainty, rather than mere quantifiable risk.

In the paper “Probabilities and payoffs”, the Counterpoint Global Insights team acknowledges similar challenges in evaluating payoffs: “One of the most challenging aspects of understanding expected value is that excess returns can be the product of high-probability events with relatively low payoffs, or low-probability events with relatively high payoffs” (Counterpoint Global Insights 2025).

In contemporary discourse, particularly within media and market analysis, the terms “risk”, “threat” and “uncertainty” are frequently conflated. However, this interchangeable usage obscures their fundamentally divergent implications. A more analytically sound approach positions predictability along a spectrum. At one end lies quantifiable risk, whereby probabilities and potential outcomes can be meaningfully assessed. Progressing along this continuum leads to deep uncertainty,11 1 In this paper we use the term “uncertainty” to reflect the “radical uncertainty” discussed by John Kay and Mervyn King. a domain where prediction is not merely challenging but conceptually ill-suited.

1.1 The drivers of deep uncertainty

In the context of deep uncertainty, prediction becomes more subjective, maybe even arbitrary. The central idea of uncertainty is that you cannot know the probability (Taleb 2016). Three factors contribute to the loss of predictability in deep uncertainty: complexity, compound parameters and unknowability (Spitz 2025a).

- Complexity.

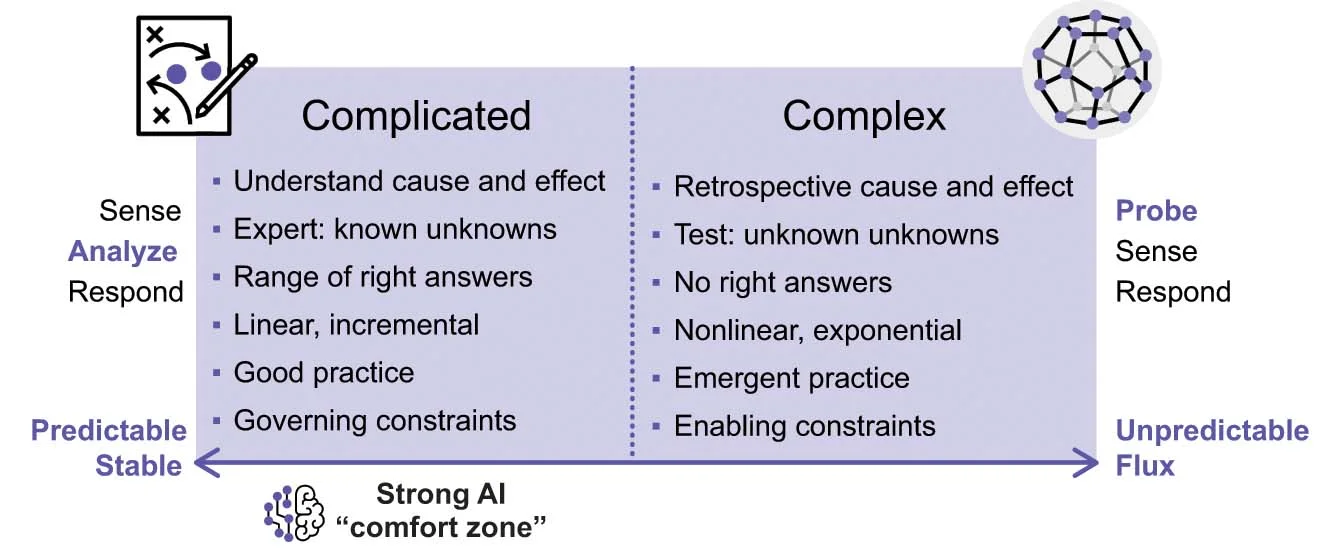

“Complicated” situations are ordered, predictable and generally linear; they present a range of right answers and can be effectively addressed by experts, with unknowns that are identifiable. In contrast, “complex” environments are dynamic and unpredictable (Snowden and Boone 2007) (Figure 1). They feature multidimensional, emergent causality, whereby outcomes cannot be reliably predicted due to unknown unknowns, and there may be no single correct solution (Page 2009). Complexity is characterized by nonlinearity – small inputs can lead to large, disproportionate effects – as well as multiple interacting causes, codependent variables and highly interconnected components (Waldrop 1992). Unlike merely complicated environments, complex systems defy straightforward analysis and require adaptive approaches.

- Compound parameters.

The proliferation of unknown or independent variables defies linear modeling.

- Unknowability.

In deep (or radical) uncertainty we may be able to enumerate many possible or plausible futures, but we will not be able to rank them in terms of likelihood, importance or possible occurrence. Stakeholders themselves do not know and cannot agree on the nature of the potential future states.

In this light, unknowability should be seen not as a failure or crisis but as an updated reality that challenges legacy approaches to decision-making and risk assessment. Despite Knight’s seminal distinction being over a century old, contemporary frameworks still struggle to fully integrate the evolving spectrum of uncertainty.

In an age increasingly described through terms such as polycrisis or permacrisis, there is a growing temptation to conflate different forms of uncertainty – particularly the profound unpredictability posed by systemic complexity – with episodic or concurrent crises:

- •

the 2022 Collins Dictionary’s Word of the Year was “permacrisis”, an extended period of instability (Collins Dictionary 2022);

- •

AXA (2023) put a spotlight on “polycrisis” in the “AXA future risks report 2023”, in which 75% of experts surveyed agreed with the statement that “risks are becoming more and more interconnected and need transversal and holistic solutions”;

- •

the World Economic Forum’s 2025 “Global risks report” raised critical issues such as geoeconomic confrontation, extreme weather events, nuclear threats, cyber risks and emerging technologies (Elsner et al 2025).

While the concept of polycrisis is not new – it was first introduced by complexity theorist Edgar Morin in the 1990s – its contemporary relevance is gaining increasing global recognition (Whiting and Park 2023). The Cascade Institute defines a global polycrisis as a condition in which crises across multiple global systems become causally entangled, producing outcomes significantly more harmful than the sum of their parts (Lawrence et al 2022). These interlocking crises amplify each other, collectively degrading humanity’s long-term prospects.

1.2 When rare is becoming less rare

To respond effectively to today’s interconnected global challenges – and to capture the opportunities they present – we must understand the evolving dynamics of a world in which rarity itself is becoming less rare. Events once considered “historic” or “unprecedented” are occurring with greater frequency across sectors, societies and systems. By 2025, a quarter into the twenty-first century, it might be asked: has unprecedented become the new normal?

The contemporary era marks a departure from the relative stability of the post-World War II global economic order, which was underpinned by international institutions and agreements aimed at enabling predictability and cooperation (Tobin 2025; Tähkäpää et al 2025). Today, the world faces simultaneous, multilayered and contradictory emerging challenges across artificial intelligence (AI), geoeconomics, climate and society – driven by rapid technological advancement, intensifying geopolitical fragmentation, escalating climate crises and the pervasive effects of digital hyperconnectivity (Sardar and Sweeney 2016). These forces are creating systemic pressures and uncertainty at a scale and velocity that arguably surpass those of previous historical transitions, which were often confined to more discrete or isolated domains.

- •

The World Uncertainty Index shows the use of the word “uncertainty” reaching Covid-19 peak levels.22 2 URL: https://worlduncertaintyindex.com (accessed April 14, 2025).

- •

The International Monetary Fund explicitly warns that the global economy is entering a new era, with uncertainty now exceeding pandemic levels, driven largely by unpredictable trade policies and geopolitical fragmentation (Gourinchas 2025).

- •

The so-called fear index (the VIX Volatility Index) reached its third-highest recorded level in April 2025, following a series of destabilizing foreign policy events. This was exceeded only during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic and during the 2007–9 global financial crisis (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development 2025).

- •

On the climate front, reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change conclude that the world is reaching tipping points, threatening irreversible impacts to Earth’s biosphere (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2022).

- •

The United States has seen a notable rise in billion-dollar weather and climate disaster events. While the 1980–2024 annual average was 9, this figure has swelled to 23 events per year over the 2020–4 period (National Centers for Environmental Information 2025).

- •

In 2025 the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set the Doomsday Clock to 89 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been, to reflect the unprecedented convergence of existential risks – including nuclear conflict, climate change, biotechnology, AI and other emerging technologies – that threaten humanity on a global scale (Mecklin 2025).

Unlike historical episodes of disruption, which were often temporally or geographically bounded, the challenges of the twenty-first century are characterized by systemic interdependence, feedback loops and nonlinear dynamics (Clearfield and Tilcsik 2018; Taleb 2005). The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ 2025 Doomsday Clock – set to an unprecedented 89 seconds to midnight – symbolizes the convergence of existential threats (Ord 2021). The accelerating interaction between technological developments, ecological instability and geopolitical fragmentation produces cascading risks that are global in scope, complex in governance and exponential in outcomes (Taleb 2016).

These levels of extreme volatility, once rare, are now increasingly commonplace. The normalization of high-impact, systemic disruptions compels a reexamination of traditional models of analysis, planning and resilience.

The gravity of this shift lies not only in the evidence of systemic stress but also in our collective failure to adapt. Much of what is labeled as polycrisis reflects conditions we have cocreated – through shortsighted governance, misaligned incentives, rigid institutions and an outdated approach to risk and uncertainty. What is often interpreted as systemic breakdown is, in many cases, a failure of foresight and agility.

This paper argues that the normalization of “unprecedented” events signals a deeper epistemic and structural transformation. It necessitates a fundamental reassessment of how we conceptualize risk, uncertainty and resilience. Adaptive frameworks must be developed that are not only reactive but capable of anticipating and navigating systemic change.

While polycrisis is often framed in terms of compounding negative outcomes, its defining feature may not be catastrophe but radical unpredictability. These systemic disruptions – whether ecological, technological, geopolitical or economic – may vary in severity, but all demand a reevaluation of the assumptions underlying our current risk models and strategic paradigms (Spitz 2025b). From an insurance perspective, major threats are increasingly interconnected, as demonstrated during the Covid-19 pandemic, when businesses and societies across diverse sectors and regions experienced simultaneous, spillover disruptions. This pattern of systemic, transversal risk is likely to persist in the future. For example, climate change can potentially trigger large-scale population migrations or lead to more severe weather events, which could strain critical information-technology and cyber infrastructures, generating new cascading effects (AXA 2024).

This paper examines the conceptual distinctions between risk and deep uncertainty, exploring their implications for insurability, decision-making and risk governance in the twenty-first century, while proposing the antifragile, anticipatory and agility (AAA) framework to address unpredictability and systemic disruption within risk and insurance domains (Spitz 2020).

2 Systemic disruption is predictably unpredictable

2.1 The age of systemic disruption

Disruption invites us to look outside our domains as we scan for early signs of change. Systemic disruption can never be evaluated as a single episodic event – its drivers are an interconnected network. Today, disruption is a constant and omnipresent force, affecting everyone, everything, everywhere.

While disruption itself is generally neither good nor bad (as its impact depends on our perspective, degree of preparation and response), systemic disruption’s effects are combinatory and cumulative (Spitz 2024b). Disruptions interact as hyperconnected networks, with nonlinear ripple effects.

Systemic disruption can trigger “super cats” – super catastrophes that go beyond isolated incidents or singular disasters (Spitz and Zuin 2022b). These events arise from multiple concurrent stressors that amplify losses and cascade through interconnected systems.

Crises such as those driven by climate change, humanitarian breakdowns or geoeconomic shocks do not occur in isolation. Accordingly, our risk assessments and future-preparedness strategies must move beyond siloed thinking.

Whether in the context of systemic disruption more generally or the adverse super cats, anticipatory thinking is no longer optional. Breaking down silos, transdisciplinary approaches and systems thinking (Meadows 2008) help mitigate and build resilience to absorb and respond to the intersecting effects of shocks.

Our objective is to identify the conditions that enable predictability. When parameters are known and stable, prediction becomes feasible. But in the presence of deep uncertainty – whereby countless variables remain unknown – predictability breaks down. As uncertainty increases and predictability declines, the risks and potential costs associated with maintaining business as usual also tend to rise.

2.2 Reframing predictability, risk and uncertainty

| Filter | Risk | Uncertainty | Deep uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|

Features | Known outcomes, variables and occurrences | Future events known, their likelihood unknown | Unknown future events or likelihood |

Outcomes | All potential outcomes are known | The possible future events that may occur are known | Unknown possible future events |

Occurrence | Likelihood of outcomes is known and measurable | Probabilities of each specific event are unknown | Stakeholders do not know or cannot agree on potential future states, let alone their probability |

Predictability | High | Medium | Low |

Knowability | Known known, known unknown | Known unknown, unknown known | Unknown known, unknown unknown |

Animals | Gray rhino, black elephant | Black elephant, black jellyfish | Black jellyfish, black swan, butterfly effect |

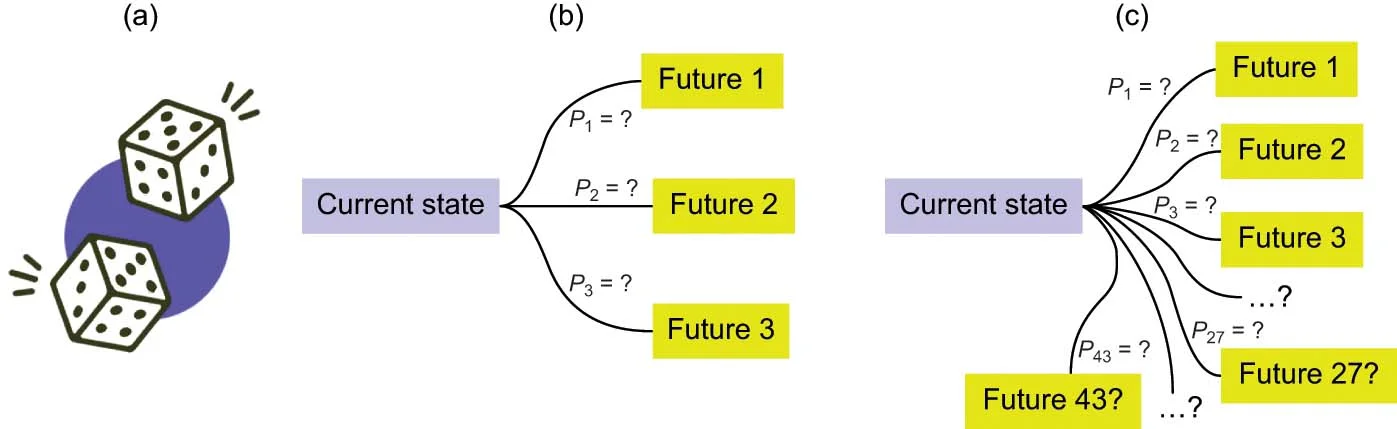

Despite the increasing sophistication of forecasting models, prediction is inherently speculative. Evaluating predictability requires understanding different degrees of certainty (see Figure 2 and Table 1).

- Risk – quantifiable uncertainty.

We use “risk” to refer to situations where relevant parameters are known, enabling outcomes and their probabilities to be assessed objectively. These are situations where statistical models can be reliable. For example, the risk of a smoker developing lung cancer can be quantified using epidemiological data.

- Uncertainty – some predictability

Uncertainty arises when possible outcomes are known but the probabilities of these outcomes are unknown or cannot be reliably estimated. Decision makers can anticipate broad categories of outcomes but cannot assign precise likelihoods. Examples include the likelihood of a recession in the next five years, or the emergence of another global pandemic.

- Deep uncertainty – least predictable.

Also known as radical uncertainty (Kay and King 2020), deep uncertainty describes a state in which future events, the possibility of their occurrence and their probabilities are all unknown. Here, stakeholders cannot agree on the nature of potential future states (Janzwood 2023). Possible outcomes are numerous and unknown. We may be able to enumerate many plausible futures but not rank them in terms of likelihood or importance. The relationships between actions, outcomes, consequences and probabilities are difficult to comprehend and agree on. For instance, climate change exemplifies deep uncertainty, as stakeholders interpret its nature and implications in fundamentally different ways: an existential threat, an economic burden, a global governance issue, a symptom of consumer capitalism or a catalyst for innovation (Hulme 2009). Another example of deep uncertainty is the societal and geoeconomic impact of AI and the potential emergence of technological singularity.33 3 Singularity refers to the point where AI surpasses human levels.

As forecasters and increasingly sophisticated models attempt to account for various degrees of uncertainty, special care is required in situations of deep uncertainty – where system complexity, nonlinearity, unknowns and interdependencies render conventional modeling approaches inadequate. The characteristics of these environments, which fundamentally limit predictability, highlight the need for alternative tools beyond statistical precision or model sophistication. In such contexts decision support should focus on informing robust choices when meaningful predictions are unattainable (Lempert 2019).

2.3 Deep uncertainty hinders predictability

Two key dynamics undermine predictability under conditions of deep uncertainty.

- (1)

Incomplete understanding of future events and their probabilities. We often lack clarity about the nature or likelihood of individual future events. What are the direct and indirect effects of climate change – its magnitude, geographic distribution and timing? What are the implications of breakthroughs in genomics, longevity or synthetic biology? How probable are rare but high-impact disruptions, such as the collapse of the internet? The list is extensive and evolving.

- (2)

Unpredictable interactions between unfolding scenarios. Even if such events occur, how will they interact with one another? Their cascading effects introduce additional layers of uncertainty, as these interactions may evolve in complex, nonlinear or chaotic ways. For instance, how might energy crises, food insecurity, pandemics, geopolitical shifts, wars, political polarization, emerging technologies and extreme weather events intertwine?

2.4 Constraints of predictions

In Superforecasting, Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner found, based on an abundance of data from their Good Judgment Project (GJP), that amateur forecasters were often more accurate than experts (Tetlock and Gardner 2015). However, answering well-defined and probabilistic questions, such as the GJP’s “Will North Korea launch a new multistage missile in the next year?”, differs significantly from answering open-ended questions about the possible future states of deeply uncertain environments.44 4 URL: https://goodjudgment.com/philip-tetlocks-10-commandments-of-superforecasting/.

In order to explore such uncertainty, forecasts can be complemented with broader approaches from the foresight field, with tools such as scenario development (Ramirez and Wilkinson 2016). Integrating predictive models with foresight methodologies enhances our ability to anticipate a range of plausible outcomes and prepare adaptive responses. We will explore the application of scenario development in Section 3.2.1.

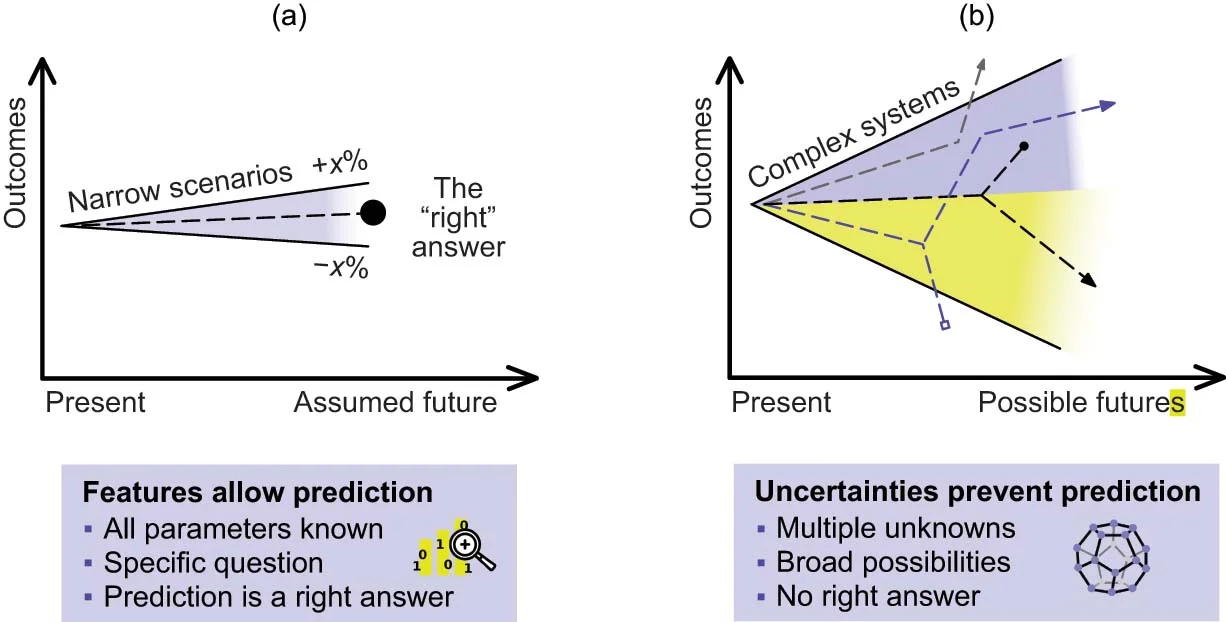

Table 2 contrasts the characteristics that underpin predictability with those that contribute to unpredictability (see also Figure 3).

| Prediction: | Foresight: |

|---|---|

| features support predictability | uncertainties prevent predictability |

| Parameters and variables are all known | Multiple unknowns |

| Narrow scenarios | Multilayered, multidimensional, nonlinear and complex |

| Most probable | Probable, plausible, possible, wild cards and “What if?” |

| A specific answer to a precise question | Uncertain, broad possibilities, no right answer |

| Well-defined, contained, discrete, linear situations | Signals, emergence, next-order impacts, dynamic, intersecting, spillover |

| Typical actors: industry experts, economists, consultancies, the GJP | Typical actors: interdisciplinary, futurists, strategic and government foresight, science fiction |

Any prediction about the future should be scrutinized. No one knows how the future will unfold. There are too many unknown knowns and unknown unknowns.

Expert consultants, economists, investment bankers, analysts, forecasters and algorithms that claim to have data-driven predictive capabilities somehow extrapolate the past. Even when some outcomes appear likely, complex adaptive systems inherently display unpredictable dynamics that interact in nonlinear ways and are difficult to decompose (Miller and Page 2007). Intersections determine outcomes, so how do any of the individual prognostics interact?

As the complexity of our hyperconnected world increases, so does the uncertainty we face. The further we attempt to project into the future, the more pronounced this uncertainty becomes. Consequently, incorporating long-term thinking into the earliest stages of decision-making can yield significant value. Ultimately, uncertainty is an intrinsic characteristic of the future (Schwartz 1991).

2.5 The complex five: know your unknowns

As famously articulated by former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (Rumsfeld 2002), we constantly need to assess what is knowable (what could be known but is currently unknown) and what is unknowable (what cannot be known at all).

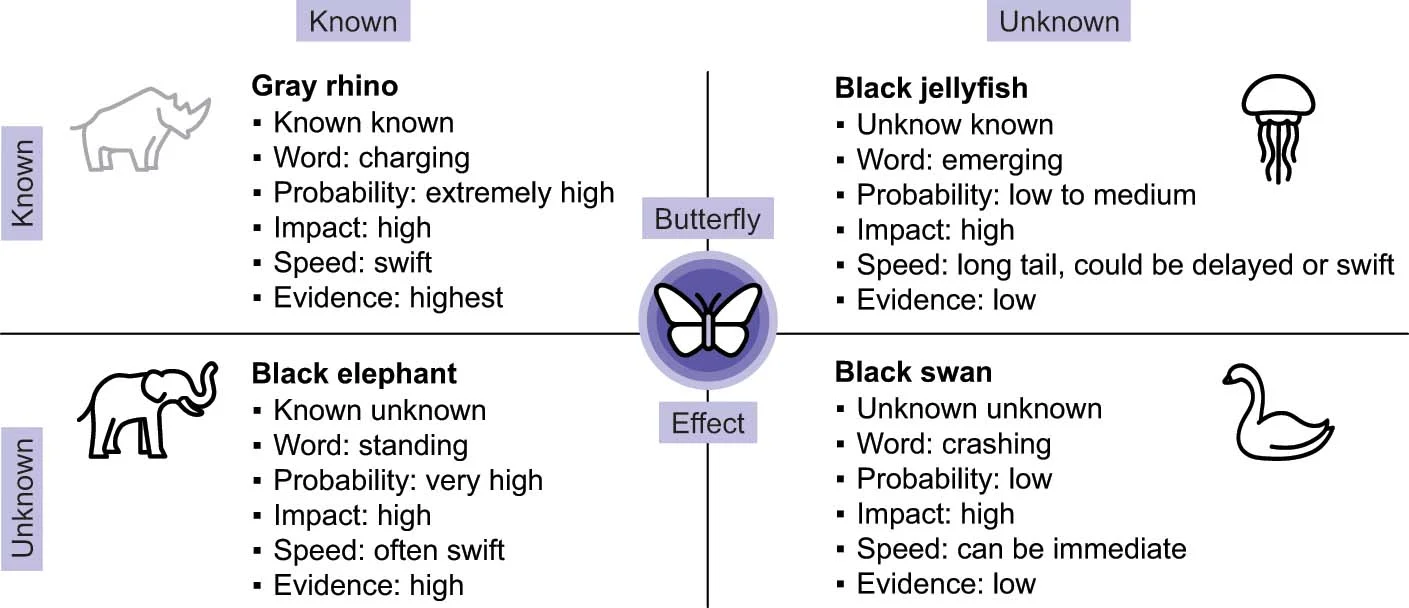

Recognizing the different types of uncertainty is a prerequisite to better anticipate unknown futures (see Figure 4 and Table 1).

- Known knowns – gray rhinos:

things we know that we know, such as “the sun rises in the morning and sets at night”. For these, we use Michele Wucker’s definition of “gray rhino” (Wucker 2016). There is no uncertainty with gray rhinos; we might treat them as unknown, but they are certain. With gray rhinos, responses often fall short because decisions come too late. To avoid being trampled, anticipate the impacts, rather than muddling along and panicking when the rhino charges.

- Unknown knowns – black jellyfish:

things we think we know but find we do not understand when they manifest. For example, increasing ocean temperatures and acidity levels prompted the perfect conditions for jellyfish population growth (Gershwin 2013). This increase then forced shutdowns of nuclear reactors around the world due to jellyfish clogging their cooling systems. Here, situations we initially believe we understand can become complex, as small changes drive larger, less predictable impacts. To describe such unknown knowns, the Postnormal Times website55 5 URL: https://postnormaltim.es/black-jellyfish. and Sardar and Sweeney (2016) use the term “black jellyfish”. To respond to black jellyfish, we need to consider snowballing effects by asking how these reverberations could cascade further. Ask “What if this expanded more than expected?”, and “What else might this impact?” Especially in contexts involving exponential developments – such as AI, climate change or other emerging technologies – these next-order impacts can accelerate, leading to irreversible tipping points.

- Known unknowns – black elephants:

things we know we do not know, including new diseases, impacts of climate change and mass human migration. These are obvious, highly likely events, but few acknowledge them. We call these known unknowns “black elephants”, based on a term attributed to the Institute for Collapsonomics (Hine 2010). Addressing black elephants requires coordinated action, stakeholder alignment and a systemic perspective attuned to complex interdependencies. In context-specific cases proactive responses are essential. Failing to respond proactively may allow black elephants to evolve into gray rhinos – visible, charging crises that can no longer be ignored.

- Unknown unknowns – black swans:

things that we do not know we do not know. For these unpredictable outliers, we use Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s “black swans” (Taleb 2007). Responses to black swans include building resilient foundations and paying attention to rare events with profound impacts. However unpredictable black swans are, we can still be anticipatory, while implementing guardrails for the randomness of our world. Look for the nonobvious. Accept randomness. Be aware of cognitive bias as the modern world becomes dominated by very rare events. When black swans appear, rise up from the devastation.

- Butterfly effects:

the flapping wings of a single majestic insect bring these animals together. The “butterfly effect”, defined by meteorologist Edward Lorenz, describes how small changes can have significant and unpredictable consequences (Dizikes 2011). To illustrate, Lorenz described a butterfly flapping its wings influencing tornado formation elsewhere.

Phrases such as “it has never happened before” or “we have never seen this” are not valid reasons to dismiss a possibility. Events previously deemed “very unlikely” are increasingly being reassessed as merely “unlikely”, or even, at times, “likely”.

“Black swans” have become convenient justifications for C-suite executives and policy makers seeking to rationalize their surprise – surprise often rooted in flawed assumptions, ignored signals or insufficient preparedness (Bazerman and Watkins 2004; Spitz 2024b).

Ultimately, all such manifestations of uncertainty share a crucial commonality: ignorance, or a lack of evidence, does not constitute evidence of absence.

2.6 Probabilities and data

2.6.1 Do not rely on modeling uncertainties to deliver certainty

In recent years data analysis has become pervasive, and the term “data-driven” has become shorthand for the ability to identify and act on industry trends. There is a growing belief that strategic challenges can be solved by accumulating more data. However, the actual utility of data – and of probabilistic modeling – is far more limited than many organizations recognize (Silver 2012). As Taleb (2013) notes: “Big data may mean more information, but also means more false information.”

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman reminds us: “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained” (Kahneman 2013). Despite the ease with which we believe we can explain the past, it is our mental hindsight biases that allow us to have confidence in these analyses.

Dealing with uncertainty means making decisions without full information. The future is inherently unpredictable. That is why it is essential to distinguish between what is a fact, what is a probability and what is simply chance.

A core problem is that many models only work under assumptions of a stable, predictable world. In reality, you cannot use modeling to extract certainty from uncertainty. Moreover, when data aligns with a model’s assumptions, it is often overindexed. Events outside the model’s scope, such as black swans, can easily render such models useless.

Bayesian probability has emerged as a prominent framework for addressing uncertainty in decision-making. Unlike deterministic models, Bayesian methods explicitly represent beliefs as probabilities (ranging from 0% to 100%), which are updated as new evidence becomes available. This inductive approach, used by both humans and machines, enables more flexible and adaptive responses to complex, evolving problems for which definitive answers are elusive.

However, all probability-based strategies, including Bayesian reasoning, are fundamentally grounded in past data. This backward-looking reliance can be risky. In 2008, for instance, the banking system, betting against black swans, lost “more than $4.3 trillion … more than was ever made in the history of banking” (US House of Representatives, Committee on Science and Technology 2009).

As our world becomes ever more complex and changes at warp speed, often incoherently, data will continue to misinform us and prompt large failures (Spitz and Zuin 2022a; Clearfield and Tilcsik 2018). Many resulting failures stem from a mix of cognitive biases, flawed assumptions and systemic oversights (Cook 2000). Taleb (2016) identifies four of these: rearview mirror thinking, silent evidence, the ludic fallacy and human error.

- •

In rearview mirror thinking a backward-looking narrative recontextualizes events with a level of nuance that may not have been accessible in real time. Retrospectively constructing a narrative around the data can conflate correlation with causation.

- •

Silent evidence, such as missing and unobserved data, can have substantial impacts that go entirely unnoticed. No predictive model can account for every aspect of reality; important variables are invariably omitted. For example, extinct species that left no fossil record introduce serious gaps and biases in our understanding of the past, limiting the accuracy of our models of historical phenomena.

- •

The ludic fallacy, or “platonofied modeling”, suggests that models are based on simplified abstractions of reality that often exclude rare, high-impact events. These idealized representations tend to assume away systemic complexity, including emergent disruptions and unquantifiable variables. For instance, a political forecasting model that, based on historical patterns such as incumbency and primary performance, gave Donald Trump a 91% chance of winning the 2020 US presidential election failed to account for the disruptive impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, illustrating the limitations of applying closed-system logic to unpredictable real-world events.66 6 URL: http://primarymodel.com/2020.

- •

Humans do not internalize probabilities well (Taleb 2005). We overestimate the likelihood of normal events and discount the danger of black swans. Specifically, we confuse the infrequency of high-impact negative events with their expected outcomes (Taleb 2016). In these asymmetric situations the likelihood of failure may be very low, but the astronomical cost of failure outweighs that low probability.

Quantitative approaches can become divorced from reality, especially when data is conflicting or inconsistent. Data can often be siloed, unreliable, unrepresentative, unmeasurable and unvalidated, and even the best data will always be historical. Much like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in physics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2016), there are fundamental limits to how precisely we can observe or measure anything in the real world – even with data.

2.7 Deadly fat tails and the psychology of outliers

In Bayesian reasoning there are challenges in assigning prior probabilities to new types of events. A question such as “What is the probability of catastrophic fires next year?” is much more challenging to imagine when you have never seen catastrophic fires. A significant limitation of a probabilistic approach is the danger of overreliance on past data when modeling the future.

The distributional form of a phenomenon offers insights into the predictability of future states. Following the terminology of mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, we can differentiate between “mild” and “wild” regimes (Mandelbrot 1997, pp. 117–125). Mild distributions, often well approximated by a Gaussian (normal) distribution, exhibit a limited range of variation.

A classic example is human height: among adults, the ratio between the tallest and shortest recorded individuals is on the order of 5. This bounded range stands in contrast to wild distributions – such as those governing wealth or book sales – where a single extreme value can vastly outweigh the rest. For mild distributions, common statistical measures such as the mean and standard deviation provide meaningful characterizations of the central tendency and dispersion, whereas in wild distributions these measures may be misleading or undefined (Mandelbrot and Taleb 2010).

The characteristic of “fat tails” (Figure 5) poses a significant threat, as individuals tend to discount the dangers of low-likelihood events, even when the outcomes would be catastrophic (Taleb 2016). We may disregard these activities because they do not appear near the center of the curve, but their abnormally high impact makes them more dangerous than we believe (Taleb 2020).

The psychological processing of outlier events often leads to attribution errors. Upon encountering an unexpected outcome, there is a tendency to attribute it to deficiencies in the preceding decision-making process. However, as evidenced in stochastic systems such as games of chance, such a direct causal link is not invariably present. A poker player may make proper decisions and still lose to the turn of an unfriendly card. As world-class poker player Annie Duke puts it: “Thinking in bets starts with recognizing that there are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about” (Duke 2018). This style of thinking is particularly helpful to prepare for more random futures, which humans perceive as being more subject to luck. When an unexpected outcome occurs, was it really an error in your thinking or behavior, or was it merely a statistical anomaly?

2.8 Artificial intelligence in decision-making raises existential questions

The growing role of AI in decision-making raises fundamental questions about its reach and our evolving relationship with it. We need to understand the nature of our own capabilities in relation to the nature of a machine’s computational rationality.

In an era marked by the inseparability of technological and existential conditions, we enter an era of “Techistentialism” (Spitz 2023). AI will increasingly provide insights that enable more-informed predictive decision-making, but humans should remain wary of an unquestioning reliance on prescriptive algorithms dictating specific decisions. Human distinctiveness may reside in our capacity for agency: the ability to experiment, improvise and exercise judgment in the face of uncertainty and emergent novelty (Nykänen and Spitz 2021).

Jean-Paul Sartre, building on Heidegger and Kierkegaard, powerfully articulated the human condition: “existence precedes essence” (Sartre 1948).77 7 The notion of existence preceding essence was originally given by Sartre in a 1945 lecture that later became the content of an introductory book to his philosophy, titled Existentialism and Humanism (L’existentialisme est un humanisme). In this view human essence is not preordained but emerges through free and conscious choice. Our capacity to define ourselves through decision-making lies at the heart of our agency. If, however, algorithmic systems begin to determine outcomes on our behalf, the locus of that agency shifts – potentially diminishing our ability to shape our own destinies (Spitz 2024a).

The assumption that AI can serve as a proxy for human decision-making warrants critical evaluation. Consider whether poor outcomes stem from AI limitations or from flawed data inputs. What might appear as incompetence may simply be algorithms acting on bad data; more or better data may not help machines make improved decisions, which does not seem to be the case for humans. Further, the growing autonomy of AI systems raises ethical, legal and even existential questions, many of which lie beyond the reach of existing regulatory frameworks or business models.

The predictive strength of AI lies in relatively stable situations that can be understood through pattern recognition at scale, given well-defined outcomes. In deeply uncertain environments, causality can only be assessed retrospectively, relationships are unpredictable and moving parts are interdependent. Here, human flexibility, creativity and responsiveness is valuable. AI may not be much better than humans in nonlinear, dynamic and complex systems (Fjelland 2020; Spitz 2020).

Recent global events have underscored these limitations. Despite access to unprecedented volumes of data, economists and policy makers failed to anticipate the highest inflation levels in decades. Even the US Treasury acknowledged its inability to foresee or explain what it termed “unanticipated shocks” to the economy. Ineffective quantitative forecasts assumed a specific and controllable inflationary trajectory (Liptak and LeBlanc 2022).

There are inherent limitations in using data to interpret the past, making the challenges of predicting the future even more significant. At any given moment, the information available for decision-making is historical, while the very purpose of decisions lies in the future, an inherently unknown territory.

Data, while often abundant, remains fundamentally retrospective. The true challenge of decision-making lies not just in statistical inference from past signals but in the crucial ability to anticipate an unknowable future: a task demanding imagination, adaptability and a necessary epistemic humility.

3 AAA framework for deep uncertainty

In today’s landscape – defined by systemic disruption, profound unpredictability and the accelerating influence of AI – the future of risk and insurability is confronting unprecedented challenges.

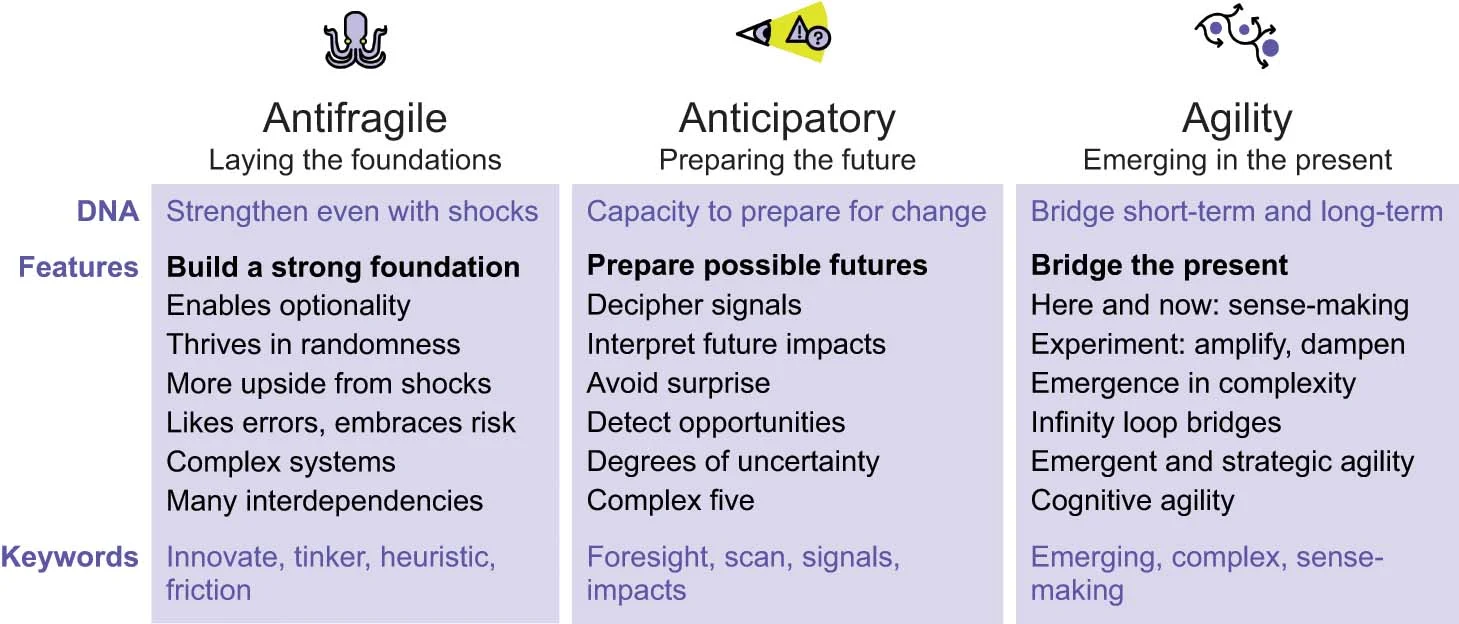

To address the deep uncertainty inherent in such an environment, we propose the AAA framework (Figure 6): a synergistic approach encompassing antifragile, anticipatory and agility principles (Spitz 2020, 2024b, 2025a).

- Antifragile:

building the right foundations to be resilient and able to take advantage of any eventuality.

- Anticipatory:

improving the capacity for anticipatory mindsets to navigate uncertainty and move beyond linear assumptions and singular outcomes.

- Agility:

developing the agility to respond to whatever futures emerge, while reconciling our preferred vision of the futures with today’s unpredictable reality.

Drawing on insights from complexity science, strategic foresight and adaptive resilience, the framework emphasizes imagination over prediction and prioritizes managing the amplitude of outcomes over relying on probability. By cultivating organizational shock absorbers and dynamic responsiveness, it empowers stakeholders to navigate volatility, build adaptive capability and seize emergent opportunities across multiple plausible futures. The framework supports decision-making under deep uncertainty (DMDU), resiliency and future-preparedness.

Below we adapt the AAA framework to explore its implications for risk management, insurability and policy design in increasingly volatile and complex environments.

3.1 Antifragile: building the foundations

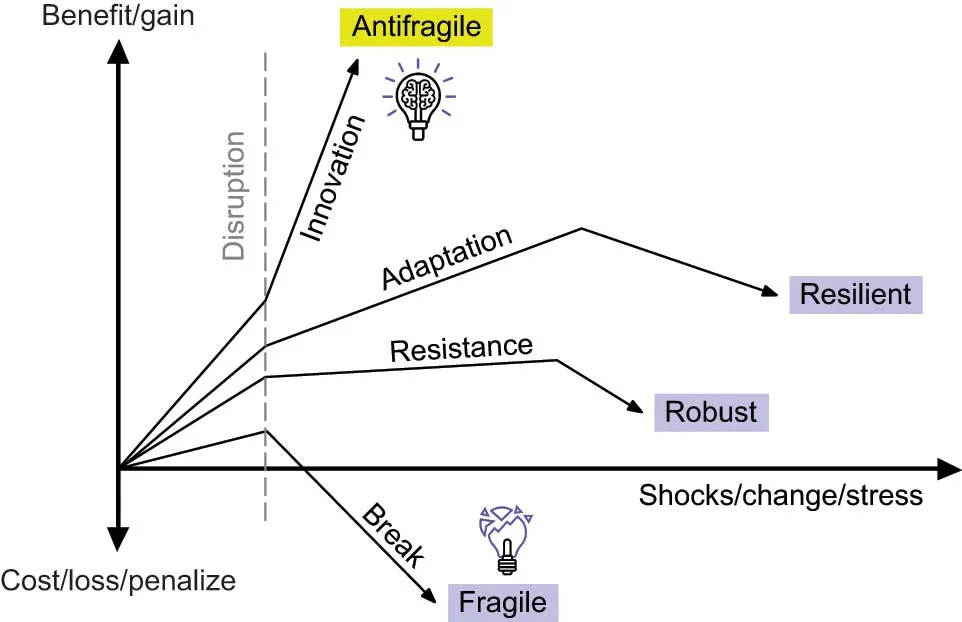

Resiliency can be defined as the ability for a system to absorb shocks and rebound promptly. It reflects an ability to respond effectively to disruption through anticipation, preparation and adaptive recovery.

The AAA taxonomy extends beyond the concept of resilience and draws on Taleb’s (2012) notion of antifragility: “Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.” Antifragile systems do not merely endure stress; they evolve and improve because of it.

Developing antifragility means focusing on the amplitude and nature of potential consequences, not just their probability. This is in contrast to “fragile” actors and environments, which are optimized for an apparently frictionless world – and are revealed to be fragile when shocks arise. Antifragile foundations provide upside from random shocks, benefiting from frequent and small errors that provide helpful lessons to build on. Thus, antifragility is best adapted to our complex world’s dynamic interdependencies.

Evaluating risk, uncertainty and data is necessary to develop antifragility, as the focus shifts from probabilities to potential outcomes. The insights derived from data can be invaluable as a feedback loop to decision-making, but they should never be confused with a proxy for the future.

Organizations and individuals move along a continuum to reach antifragility, which is a higher objective than being merely resilient (Figure 7).

3.1.1 Fragility and asymmetric exposure to shocks

Fragile systems are particularly vulnerable to disorder and uncertainty, tending to suffer disproportionately from external shocks. This vulnerability is rooted in an asymmetric relationship between the shock and its impact: the negative consequences experienced by fragile systems often exceed the magnitude of the initiating change.

This asymmetry means that even relatively small disturbances can trigger outsized, sometimes irreversible, consequences. Fragile systems lack sufficient buffers or redundancy, making them especially susceptible to fat-tail events. While such events may be statistically rare, their potential to cause extreme damage is magnified when combined with fragility. As a result, fragility entails not only greater risk exposure but also an increased likelihood of catastrophic failure in the presence of disorder.

This dynamic is particularly evident in the context of climate change. Assessment reports from the IPCC have emphasized that mitigation alone is insufficient; there is an urgent need to also prioritize resilience and adaptation (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2022). Echoing this concern, the issue of insurability in the face of the climate crisis is actively debated within the insurance industry. While some stakeholders have raised concerns warning that the escalating climate crisis could reach a point where “the financial sector [is] unable to operate … [and] insurers will no longer be able to offer cover for many climate risks” (Carrington 2025), others emphasize that insurability remains possible through a shift toward preventive measures, improved risk-reduction strategies and stronger public–private collaboration (Decoene and Weder di Mauro 2025). This growing unease reflects broader anxieties about systemic fragility in the face of compounding environmental impacts (Eickmeier et al 2024).88 8 See also the European Central Bank’s “The climate insurance protection gap” web page. URL: http://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/climate/climate/html/index.en.html.

3.1.2 Example of antifragile financial strategy

Popular financial theory champions efficient capital deployment, which includes using spare cash to buy back a company’s own shares. Every year, global share buybacks consistently exceed USD500 billion. Because share buybacks can increase stock prices, they can pacify stakeholders and hit short-term market targets. However, this short-lived boost comes with the lasting disappearance of cash reserves. Companies that are inclined to share buybacks find themselves more vulnerable. Competing short-term interests can frame challenges and responses in competing fashions, leading to inaction and parochial understandings of complex issues (Boin 2014).

Cash-rich companies exhibit a different narrative during crises. Past market upheavals (eg, the 2008 crash, the Covid-19 pandemic, interest rate hikes in 2022–23, and trade wars and market volatility in 2025) have shown that holding cash, seemingly inefficient in a stable world, provides crucial optionality when reality bites. Armed with substantial cash reserves and liquidity, “overcapitalized” antifragile organizations can invest and thrive, while fragile, overleveraged companies may face failure or require bailouts. This clash between financial theory and reality challenges assumptions about capital allocation (Taleb 2012).

According to Axios (Salmon 2025), Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 companies returned a record USD1.6 trillion to shareholders in 2024, based on data from S&P Dow Jones indexes. Notably, approximately 60% of this amount was distributed through share buybacks. As the global economy faces persistent and severe shocks, this capital is no longer available for strategic use.

3.1.3 Loose coupling as an antifragile feature

Complex systems are characterized by multiple relationships and interconnections. Financial markets, global supply chains and social networks often exhibit a high degree of tight coupling. In such systems, small ripples in quiet waters become tidal waves.

By creating significant interdependence between system components, tight coupling introduces fragility. Disruptions in one area can quickly propagate, amplifying the impact (Clearfield and Tilcsik 2018). This vulnerability is exacerbated when systems operate with narrow margins for error and limited buffers. Historical examples of systemic contagion include the 2007–9 global financial crisis, global supply chain breakdowns during Covid-19, Europe’s 2021 energy crisis and CrowdStrike’s 2024 single point of failure due to a defective software update. Emerging US trade policies in 2025, particularly around tariffs, may similarly increase systemic risk by reconfiguring interdependencies and reducing flexibility.

In contrast, loose coupling reduces the risk of single points of failure, emphasizing decentralization, distribution and flexibility. These attributes enable systems to adapt, self-organize and absorb shocks through built-in redundancy. Loosely coupled systems are better positioned to contain localized disruptions, allowing for agility and strategic responsiveness rather than systemic collapse.

Moreover, loose coupling is conducive to experimentation and learning, supported by feedback loops that help the system evolve over time. This dynamic is fundamental to antifragility: not only withstanding disruption, but improving because of it.

3.1.4 Antifragility for a postpredictive world

For Taleb (2012), a critical criterion for assessing antifragility is a system’s response to disorder: specifically, whether it derives greater benefit than harm from random shocks. If so, the system may be considered antifragile (Figure 8).

Efficiency is fragile. Optimized systems, designed to reduce waste, often eliminate the very buffers needed to absorb unexpected shocks. Antifragile organizations build in redundancy, slack and modularity as strategic assets. Functional inefficiencies are not liabilities but can serve as reserves of adaptability. This enables systems to respond dynamically and recover quickly, turning stress into innovation rather than breakdown.

Antifragility is as much a mindset as it is a structural strategy. Organizations must embrace friction, diversity and discomfort as sources of strength. This involves shifting away from hierarchical, centralized control toward distributed, emergent and networked systems that can self-organize in the face of change. Language evolves accordingly – moving from certainty to questioning, from control to autonomy and from legacy structures to adaptive governance.

In summary, antifragile thinking requires abandoning rigid narratives and engaging in deep inquiry. Socratic questioning and first-principles reasoning allow decision makers to deconstruct complexity, challenge assumptions and reimagine foundational structures. In a risk and insurance context this might mean rethinking actuarial models, regulatory frameworks or the very notion of insurability in a world where past data is no longer always a reliable guide.

3.2 Anticipatory: preparing the futures

The term “anticipatory” is closely linked to the field of strategic foresight (Stephens et al 2025). Anticipatory leadership embodies a form of futures intelligence – one that entails identifying and interpreting weak signals through horizon scanning before they develop into significant events or trends (Malmgren 1990). It also involves envisioning second- and third-order effects and detecting emerging patterns across complex systems. This approach enables proactive preparation by highlighting potential risks, opportunities and systemic shifts.

Mitigation is a key dimension of anticipatory thinking. It enables proactive actions aimed at reducing the severity, likelihood or impact of potential future challenges. The overarching goal is to prevent harm, minimize adverse consequences and enhance systemic resilience.

Next, we examine adaptive methodologies designed for anticipating and managing systemic disruption.

3.2.1 Scenarios: alternatives to relying on assumptions

Strategic foresight offers alternatives to relying on assumptions, as these can be limiting and costly. Foresight is the capacity to systematically explore possible futures, drivers of change and next-order impacts in order to inform short-term decision-making. This is often achieved through scenario planning, which serves as an alternative or complement to linear strategic planning, and relies on the fundamental principle of challenging the assumptions we can have about the future.

The idea of using scenarios for situations of high uncertainty was originally developed by Herman Kahn (at the RAND Corporation) for military strategy in the 1950s, following the dropping of the first atomic bomb in World War II, when the world was confronted with the unprecedented possibility of nuclear annihilation. Pierre Wack (at Royal Dutch Shell) adopted scenarios for business in the 1970s (Chermack 2017; Chermack et al 2001). The fundamental departure of this idea is that futures are different from the past (Schoemaker 2022). Good scenarios help solve problems differently because they can illuminate new possibilities and ignite hope.

Scenario planning allows the exploration of many plausibilities without relying on fixed assumptions or singular, arbitrary outcomes. The purpose of scenario development is preparation, not prediction (Kupers and Wilkinson 2014). This allows us to scrutinize potential consequences and build the capacity to sustain viability even given serious outcomes. As longer-term thinking and complex problem-solving can be difficult to address with discrete linear strategic planning (Mintzberg 1994), foresight prepares us for the swerves and shocks that linear planning may overlook (Hines and Bishop 2006).

3.2.2 Futures wheel to imagine next-order impacts

The “futures wheel” is a structured method used to explore both the direct and indirect consequences of a specific change (Glenn 1972). It can provoke practitioners to imagine cascading higher-order changes. This iterative approach to creative thinking helps uncover unexpected or counterintuitive possibilities and imagine unanticipated consequences and possible wild-card events.

3.2.3 Premortem analysis to enhance anticipatory capabilities

A postmortem traditionally refers to the examination of a failure in order to determine its causes and derive lessons for future improvement. In contrast, the premortem technique, introduced by Gary Klein, shifts the analytical lens from retrospective to prospective (Klein 2007). Rather than asking what did go wrong, a premortem asks what could go wrong.

This approach is particularly valuable in deeply uncertain environments, where overconfidence and groupthink can obscure emerging critical risks. By fostering a mindset of “prospective hindsight”, premortems help participants surface hidden vulnerabilities, challenge assumptions and generate actionable insights before significant resources are committed.

The Rogers Commission’s investigation into the 1986 Challenger disaster highlighted that concerns about the O-ring seals ultimately did not alter the decision to launch the shuttle, due to cascading miscommunications and the lack of a “well structured and managed system emphasizing safety” (Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident 1986). We can only speculate how an organizational culture that conducted premortem exercises – such as by asking, “What might make Challenger explode?” – might have surfaced concerns about the O-ring seals and potentially altered the course of decision-making.

Cass R. Sunstein advocates for anticipatory governance, akin to a policy-level premortem, when facing uncertain but potentially catastrophic risks. He writes: “In the face of unknown probabilities of genuine catastrophe for which ‘wait and learn’ is imprudent, it is reasonable to take strong protective measures…. And if we end up taking too many precautions, well, so be it” (Sunstein 2024). In conditions of high uncertainty and high stakes, proactive and precautionary policies are not only justified – they may be necessary.

The following sections explore two applications that show how embedding anticipatory systems within organizations can enhance resilience.

3.2.4 Application: preventative technology

Earth-observation technology is playing a transformative role across environmental domains, from validating claims in carbon credit markets to enhancing forest management. Satellite-based platforms, combined with machine learning, now enable real-time monitoring and verification of carbon emissions reductions and forest conservation outcomes.

AI is also reshaping wildfire risk management. Systems powered by AI analyze real-time weather, vegetation and historical fire data to forecast wildfire likelihood, prioritize areas for controlled burns and guide the strategic deployment of firefighting resources (University of Canterbury, New Zealand 2025). These capabilities enable more timely, targeted and resilient interventions.

Wildfires already impose substantial economic costs, with recent global damages estimated in the tens of billions of US dollars annually (Salas 2024) – a figure expected to rise as climate-related risks intensify. The integration of Earth-observation and AI technologies offers a proactive, preventative approach to risk mitigation (du Rostu 2025), supporting environmental integrity and economic resilience in a warming world.

3.2.5 Application: preventive (ex ante) insurance

The integration of wearable technologies, such as smart glasses and fitness trackers, is poised to transform health care and insurance by enabling earlier disease detection and proactive interventions. These devices, equipped with biosensors and connected to machine learning systems, support continuous health monitoring and real-time diagnostics, shifting the industry from traditional ex post insurance models – in which compensation follows adverse events – toward ex ante approaches focused on prevention (Lanfranchi and Grassi 2022).

Insurers are increasingly leveraging predictive analytics, ubiquitous sensors and biotechnology to identify health risks early and facilitate tailored preventive care. For example, Verily’s Onduo platform integrates wearable sensors, personalized coaching and AI-driven insights to manage chronic conditions such as diabetes, illustrating the practical application of ex ante insurance models.

Smart glasses, as part of this ecosystem, offer the potential for passive, continuous biometric monitoring, supporting early-stage diagnostics without disrupting daily life (Smuck et al 2021). This anticipatory model reframes the insurer’s role from a reactive payor to a proactive partner in health management. These glasses could support algorithm-driven preventive interventions by continuously monitoring eye health, behavioral patterns or vital signs. In this scenario, eyewear might not only augment or significantly impact the roles of smartphones and fitness trackers but also assume roles traditionally held by optometrists and personal trainers.

The convergence of digital health, a growing individual focus on well-being and insurtech is blurring traditional boundaries, with technology companies increasingly positioned as hybrid providers of insurance, benefits and preventive-care services. As these trends accelerate, foundational questions around data privacy and governance, perceived invasive monitoring, accountability in care delivery, and evolving definitions of insurability will reshape the insurance value chain.

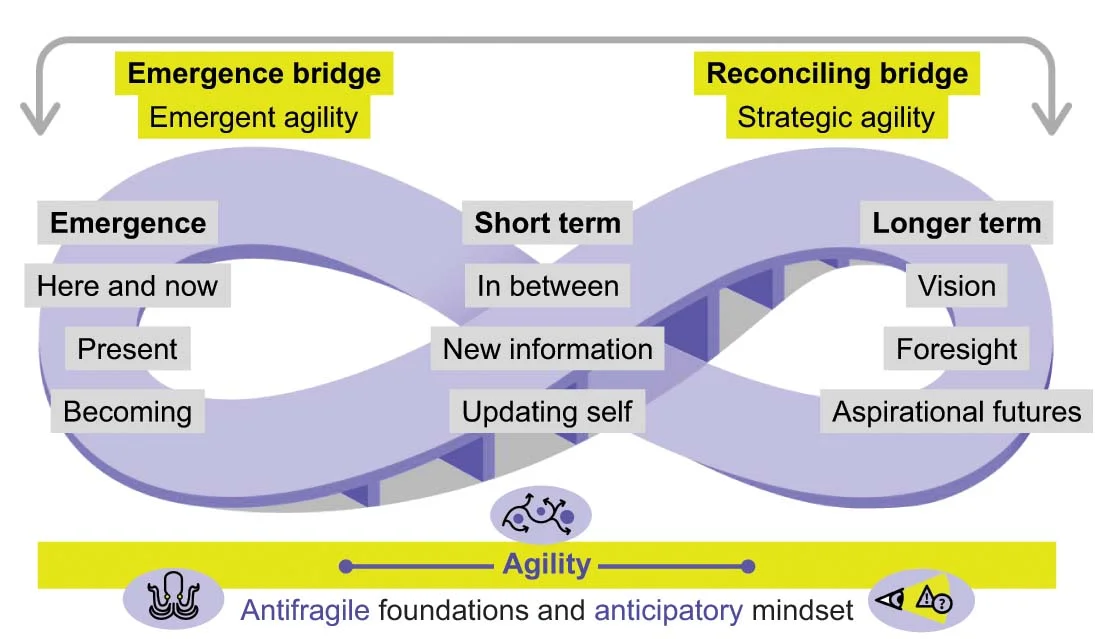

3.3 Agility: emerging in the present

The third pillar of the AAA framework explores agility through multiple perspectives. A key concept is emergence, which is the process whereby novel collective behaviors, properties or phenomena emerge when the parts of a system interact in a wider whole. As the separate parts would not have these properties on their own, emergence generates synergies between individual aspects that occur only thanks to their interactions.

Two properties of agility are used to describe what is required for emergence in complex environments.

- (1) Emergent agility:

our ability to emerge in the “here and now”. This involves real-time trial and error, as there may be no right answers to guide us.

- (2) Strategic agility:

our agility in reconciling different time horizons. This means reconciling the strategic long-term vision with short-term decision-making and problem-solving.

We want to amplify or dampen our evolving behaviors based on feedback, allowing instructive patterns to emerge. Lean and nimble cells that attack problems independently can influence leverage points to create attractors for emergence (Meadows 1999). These agile strategies have risen in all sorts of areas, from nature itself to lean startups.

In contrast, our uniform, centralized and hierarchical organizations are not agile. Most move slowly, continuing with unchanged approaches. These fragile strategies do not respond well to constantly changing circumstances.

A frequent criticism of long-term thinking is that the time horizons explored are too far away, too uncertain. The mistake with that is treating the future as distinct from the present. There is no either/or choice between the present and futures (Cunzeman and Dickey 2023). Only the present exists, so all our decisions about long-term futures need to be translated to the now.

3.3.1 Cognitive agility: problem-solving for systemic risks

Cognitive agility equips individuals to respond to change with a systemic perspective, experiment with emergent behaviors and integrate insights across disciplines. Where patterns are often difficult to discern, both novel and established risks are emerging and evolving in unprecedented ways.

In The Collapse of Complex Societies Joseph Tainter studies the collapse of civilizations (Maya, Chacoan, Roman) and finds that, as humans and institutions become less versatile in problem-solving, collapse ensues (Tainter 1989). Societies collapse as they reach a point of rapidly declining marginal returns on their investments in problem-solving capacity. Sustainable futures may be contingent on humanity’s ability to problem-solve ourselves out of the most complex, systemic and existential risks.

3.3.2 Adaptive decision-making: infinite loop bridges

What we refer to as infinite loop bridges do not merely help us “get to the other side”. Rather, they represent ongoing transitions, continuously crossed as circumstances evolve, perceptions shift and experiential learning occurs (Figure 9). They are a metaphor for dynamic, nonlinear thinking that integrates strategic vision with adaptive decision-making.

Situations are inherently fluid. Context changes, and possibilities evolve. As forecaster Paul Saffo suggests with his principle of “strong opinions, weakly held”, effective decision-making requires a willingness to revise hypotheses in light of new evidence (Educom Review Staff 1998).

In deeply uncertain environments, decision-making is an emergent and iterative process, continuously shaped by feedback. Unlike traditional “predict then act” approaches, DMDU supports adaptive strategies that remain effective across multiple plausible futures (Lempert 2025).

The concept of infinite loop bridges also challenges the binary distinction between short-term and long-term thinking. It encourages a mindset that emphasizes action in the present while acknowledging that imagined futures are contingent on current choices and perceptions (McGonigal 2022).

3.3.3 Feedback loops in supporting emergent and strategic agility

Jakarta’s flood management challenges, shaped by low-lying topography, climate change and rapid urbanization, illustrate how feedback loops can drive both emergent agility in crisis response and strategic agility in resilience planning. The PetaBencana.id platform exemplifies this dual role by integrating real-time, crowdsourced social media reports, “Internet of Things” sensor data (eg, water levels, rainfall) and government inputs into a unified, open-access system (IBM Institute for Business Value et al 2025). Emergent agility is enabled through decentralized, adaptive decision-making: residents’ microblogged flood updates are algorithmically filtered and cross-validated with sensor data, enhancing situational awareness and guiding the emergency response. Strategic agility arises through the aggregation of real-time and historical data to inform infrastructure upgrades, policy changes such as groundwater extraction limits and public preparedness initiatives. This continuous feedback loop supports both rapid crisis response and iterative system improvement, aligning with frameworks of organizational agility that emphasize responsiveness and foresight. The platform’s widespread adoption and integration into Indonesia’s national disaster protocols demonstrate how hybrid feedback mechanisms can bridge grassroots engagement and institutional action, driving trust and collaborative urban governance. Jakarta’s experience highlights the importance of data interoperability and community codesign in scaling adaptive systems for climate-vulnerable megacities.

However, the effectiveness of such systems hinges on integrating agility with anticipation and antifragility, as outlined in the AAA framework. Feedback from agile operations must inform anticipatory governance practices, such as scenario planning for climate-driven extreme weather, as well as incentive structures that favor antifragility, such as investments in resilient infrastructure. Without this integration, efforts to manage systemic risks may fall short. It is therefore essential to adapt governance and incentive systems to be more anticipatory, ensuring that necessary transformations are proactively implemented in preparation for future shocks and disruptions (Spitz 2025a).

4 Conclusions: future-preparedness

4.1 Foresight, resilience and agility

To navigate today’s complex challenges, decision makers must adopt frameworks that enable them to do the following.

- Acknowledge limitations.

Recognize the dangers of overreliance on probabilistic models, particularly in domains marked by deep uncertainty. Expect more unexpected events, regardless of what the historical data suggests.

- Prepare for nonlinearity.

Build systems capable of evaluating asymmetric risks and absorbing shocks, or even gaining strength from unexpected events.

- Build anticipatory capabilities.

Regularly explore “what-if?” scenarios, especially those considered unlikely, to better prepare for surprises (Desbiey 2025).

- Develop agility.

In complex and uncertain environments, unknown unknowns are inevitable. Cultivate agility to adapt swiftly and make informed decisions in deep uncertainty, even in the absence of immediate answers.

Ultimately, no matter how antifragile, anticipatory or agile an organization becomes, the AAA framework is only effective when activated by agency – making informed choices, guided by alignment with both internal values and the external environment. Agency, however, is like an unexercised option: without action, it holds no value.

As our understanding of these topics deepens, our focus should shift toward exercising agency and ensuring effective execution.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- AXA (2023). AXA future risks report 2023. Report, October 30, AXA. URL: http://www.axa.com/en/news/2023-future-risks-report.

- AXA (2024). AXA future risks report 2024. Report, October 14, AXA. ULR: http://www.axa.com/en/news/2024-future-risks-report.

- Bazerman, M. H., and Watkins, M. D. (2004). Predictable Surprises: The Disasters You Should Have Seen Coming, and How to Prevent Them. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Boin, A. (2014). Designing resilience: leadership challenges in complex administrative systems. In Designing Resilience: Preparing for Extreme Events, Comfort, L., Boin, A., and Demchak, C. C. (eds), Chapter 7. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Carrington, D. (2025). Climate crisis on track to destroy capitalism, warns top insurer. The Guardian, April 3. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/apr/03/climate-crisis-on-track-to-destroy-capitalism-warns-allianz-insurer.

- Chermack, T. J. (2017). Foundations of Scenario Planning: The Story of Pierre Wack. Routledge, London.

- Chermack, T. J., Lynham, S. A., and Ruona, W. E. A. (2001). A review of scenario planning literature. Futures Research Quarterly 17(2), 7–32.

- Clearfield, C., and Tilcsik, A. (2018). Meltdown: Why Our Systems Fail and What We Can Do about It. Penguin Press. URL: http://www.meltdownbook.net/meltdown.

- Collins Dictionary (2022). A year of permacrisis. Blog Post, November 1, Collins Dictionary. URL: https://blog.collinsdictionary.com/language-lovers/a-year-of-permacrisis/.

- Cook, R. I. (2000). How complex systems fail. Working Paper, April 21, Cognitive Technologies Laboratory, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. URL: http://www.adaptivecapacitylabs.com/HowComplexSystemsFail.pdf.

- Counterpoint Global Insights (2025). Probabilities and payoffs: the practicalities and psychology of expected value. Report, February 19, Morgan Stanley. URL: http://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_probabilitiesandpayoffs.pdf.

- Crichton, D. (1999). The risk triangle. In Natural Disaster Management, Ingleton, J. (ed), pp. 102–103. Tudor Rose, Leicester.

- Cunzeman, K. C., and Dickey, R. (2023). Project North Star: strategic foresight for US grand strategy. Report, July, The Aerospace Corporation. URL: https://csps.aerospace.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/Cunzeman-Dickey_ProjectNorthStar_20230706.pdf.

- Decoene, U., and Weder di Mauro, B. (2025). Insuring the world of tomorrow. Report, March 10, Centre for Economic Policy Research. URL: https://bit.ly/4jdGLi3.

- Desbiey, O. (2025). What if … we experienced the future? AXA foresight report 2025. Report, April 8, AXA. URL: http://www.axa.com/en/press/publications/2025-axa-foresight-report.

- Dizikes, P. (2011). When the butterfly effect took flight. MIT Technology Review, February 22. URL: http://www.technologyreview.com/2011/02/22/196987/when-the-butterfly-effect-took-flight/.

- du Rostu, P. (2025). AXA Digital Commercial Platform: prevention is key to keeping the world insurable. Article, January 9, AXA. URL: http://www.axa.com/en/news/leaders-voice-axa-digital-commercial-platform.

- Duke, A. (2018). Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts. Portfolio, New York.

- Educom Review Staff (1998). Paul Saffo interview: betting on “strong opinions weakly held”. Educom Review 33(3). URL: http://www.educause.edu/apps/er/review/reviewArticles/33340.html.

- Eickmeier, S., Quast, J., and Schüler, Y. (2024). Large, broad-based macroeconomic and financial effects of natural disasters. VoxEU, May 26, Centre for Economic Policy Research. URL: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/large-broad-based-macroeconomic-and-financial-effects-natural-disasters.

- Elsner, M., Atkinson, G., and Zahidi, S. (2025). Global risks report 2025. Report, January 15, World Economic Forum. URL: http://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2025/.

- Fjelland, R. (2020). Why general artificial intelligence will not be realized. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, Paper 10 (https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0494-4).

- Gershwin, L.-A. (2013). Stung! On Jellyfish Blooms and the Future of the Ocean. University of Chicago Press.

- Glenn, J. C. (1972). Futurizing teaching vs futures course. Social Science Record 9(3), 26–29.

- Gourinchas, P.-O. (2025). The Global Economy Enters a New Era. Article, April 22, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. URL: http://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2025/04/22/the-global-economy-enters-a-new-era.

- Hine, D. (2010). Black elephants and skull jackets: a conversation with Vinay Gupta. Dark Mountain, Issue 1, pp. 32–46.

- Hines, A., and Bishop, P. (2006). Thinking about the Future: Guidelines for Strategic Foresight. Social Technologies, Washington, DC.

- Hulme, M. (2009). Why We Disagree about Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity. Cambridge University Press.

- IBM Institute for Business Value, National Academy of Public Administration, IBM Center for the Business of Government and IBM (2025). Drought, deluge, and data: success stories on emergency preparedness and response. Report, April, IBM. URL: https://lnkd.in/ekQwW5zH.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022). Summary for policymakers: IPCC sixth assessment report – climate change 2022; impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Report, February, IPCC. URL: http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/.

- Janzwood, S. (2023). Confidence deficits and reducibility: toward a coherent conceptualization of uncertainty level. Risk Analysis 43(10), 2004–2016 (https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14008).

- Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

- Kay, J., and King, M. (2020). Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making beyond the Numbers. W. W. Norton & Company, New York.

- Keynes, J. M. (1921). A Treatise on Probability. Macmillan and Co., London.

- Klein, G. (2007). Performing a project premortem. Harvard Business Review 85(9), 18–19. URL: https://hbr.org/2007/09/performing-a-project-premortem.

- Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA.

- Kupers, R., and Wilkinson, A. (2014). The Essence of Scenarios: Learning from the Shell Experience. Amsterdam University Press.

- Lanfranchi, D., and Grassi, L. (2022). Examining insurance companies’ use of technology for innovation. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice 47, 520–537 (https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-021-00258-y).

- Lawrence, M., Janzwood, S., and Homer-Dixon, T. (2022). What is a global polycrisis? And how is it different from a systemic risk? Technical Paper, September 16, Cascade Institute, Royal Roads University, Victoria, BC. URL: https://cascadeinstitute.org/technical-paper/what-is-a-global-polycrisis/.

- Lempert, R. J. (2019). Robust decision making (RDM). In Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty: From Theory to Practice, Marchau, V. A. W. J., Walker, W. E., Bloemen, P. J. T. M., and Popper, S. W. (eds), pp. 23–51. Springer (https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05252-2_2).

- Lempert, R. J. (2025). Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty and the Great Acceleration. Report, April 24, RAND. URL: http://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA3789-1.html.

- Liptak, K., and LeBlanc, P. (2022). Treasury secretary concedes she was wrong on “path that inflation would take”. CNN, June 1. URL: http://www.cnn.com/2022/05/31/politics/treasury-secretary-janet-yellen-inflation-cnntv/index.html.

- Malmgren, P. (1990). Signals: How Everyday Signs Can Help Us Navigate the World’s Most Turbulent Economy. Core Music Publishing, Toronto.

- Mandelbrot, B. B. (1997). Fractals and Scaling in Finance: Discontinuity, Concentration, Risk. Springer.

- Mandelbrot, B. B., and Taleb, N. N. (2010). Mild vs. wild randomness: focusing on those risks that matter. In The Known, the Unknown, and the Unknowable in Financial Risk Management: Measurement and Theory Advancing Practice, Diebold, F. X., Doherty, N., and Herring, R. (eds), pp. 47–58. Princeton University Press.

- McGonigal, J. (2022). Imaginable: How to See the Future Coming and Feel Ready for Anything – Even Things That Seem Impossible Today. Spiegel & Grau, New York.

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: places to intervene in a system. Working Paper, Academy for Systems Change. URL: https://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/.

- Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT.

- Mecklin, J. (2025). Closer than ever: it is now 89 seconds to midnight. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 28. URL: https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/2025-statement/.

- Miller, J. H., and Page, S. E. (2007). Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life. Princeton University Press.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review 72(1), 107–114. URL: https://bit.ly/3SNfb0c.

- National Centers for Environmental Information (2025). U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. Data Set, January 21, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (https://doi.org/10.25921/stkw-7w73).

- Nykänen, R., and Spitz, R. (2021). An existential framework for the future of decision-making in leadership. In Leadership for the Future, Mengel, T. (ed), pp. 233–265. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Ord, T. (2021). The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Hachette Books, New York.

- Page, S. E. (2009). Understanding complexity. Course Material, The Great Courses.