Investment Risks: Market, Credit and Liquidity Risk

Introduction

Risk Management

Financial Economics of Insurance

Underwriting Risks: Life Risk and Non-life Risk

Investment Risks: Market, Credit and Liquidity Risk

Non-financial Risks: Operational and Business Risk

The Financial Crisis: Consequences for Insurers

Insurance Supervision: From Solvency I to Solvency II

Insurance Supervision Outside the EU

Pillar I of Solvency II

Pillar II of Solvency II

Pillar III of Solvency II

Accounting Regulations

Banking Supervision: From Basel I to III

Management Control

Organising Risk Management

Bringing All the Strands Together

This chapter will discuss investment risks, which are also known as financial risks. These risks mostly arise from the investment process of insurers, but some are also due to underwriting activities. The credit risk of reinsurers is one example. An important risk in insurance is interest rate risk, having an impact on both the liability and asset side of the insurers’ balance sheets. We will see in this chapter how asset and liability management takes place to address this risk. This chapter will also address three main investment risks: market risk, credit risk and liquidity risk, including the main sub-risks. As in the previous chapter, we will start by explaining each risk before going into detail on how to control and measure the risk. For each risk, this chapter will explore the relevant economic capital models. Liquidity risk is a special risk type, as will be seen later in this chapter, because economic capital is a less-suitable method for addressing liquidity risk. We will start, however, with market and credit risk.

WHAT IS MARKET RISK?

An insurer invests its technical provisions and its equity capital as part of its primary function as a financial institution. The investment process is at the service of the core activity as an insurer, ie, providing insurance products. Although investments are generally perceived as “risky”, that is not necessarily the case. One can also invest in government bonds – something that insurers definitely do. At the same time, we have seen in the late 2000s that government bonds are not completely risk-free either during the sovereign bond crisis. Chapter 7 explores the financial crisis in more detail. No insurer invests its total investment portfolio in stocks – traditionally believed to be the most risky asset category. All in all, we can be sure that fluctuations on the financial markets can have consequences for insurers. This phenomenon is called market risk.

Market risk is the risk of decreases in value by changes in market variables, such as the interest rates, equity prices, exchange rates, real estate prices and the like. This also includes ALM.

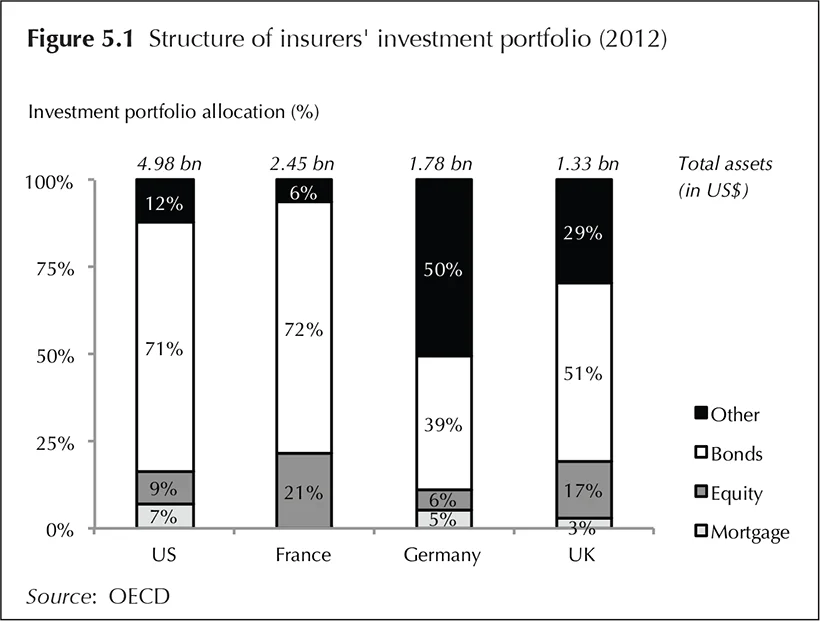

Most of the assets of an insurer consist of bonds and equity (see Figure 5.1). Fixed income investments are assets with a fixed interest rate: government bonds, corporate bonds and mortgages. Other assets such as shares and real estate investments do not have agreed returns in advance, and generally involve more risk than fixed income investments. The expected return on these assets is, however, higher because they include a compensation for that risk. We see that equity investments in both Europe and the US are 10–20% of the portfolio. That has, however, shifted since the financial crisis, bringing down the level of equity investment in Europe due to de-risking. This differs per country, and those countries with large unit-linked portfolios will have a higher share of equity investments, such as the UK. Although differences in market composition might still occur, regulatory differences will decrease after Solvency II (see Chapter 8 and further). Another interesting difference per country is the amount of corporate versus government-related bonds. In the US, almost 55% of the asset portfolio consists of government bonds, with 16% in corporate bonds. In the UK, for instance, government bonds are roughly 20% and corporate bonds are about 31% of the total investment portfolio according to the OECD.

Apart from the above-mentioned asset categories, insurers often have derivatives such as options and swaps in the portfolio to cover risks. This kind of coverage of market risks is called hedging. Although these derivatives are complex products, the ability to introduce these effectively is gradually increasing. Besides, financial market parties are increasingly anticipating the needs of insurers and offering special derivatives. Examples are inflation-linked or mortality bonds.

The investment process of an insurer is not a stand-alone process. Rather, it is linked to the underwriting process, because the profile of the insurance liabilities is an important driver. An insurer invests in such a way that assets are sufficient to cover the future liabilities. In other words: the assets are chosen in such a way that the cashflows from investments are matched as well as possible to the benefit payments to policyholders, ie, the technical provisions. However, assets are not usually allocated to individual insurance policies on a one-to-one basis. The investment process takes place on an aggregated level, and it is thus possible to benefit from economies of scale.

The value of the investments is subject to the fluctuations of financial markets, despite the fact that the investments are matched to the technical provisions. If the liabilities are perfectly “matched” (Panel 5.1 expands on the term), these fluctuations have no consequences for the insurer as a whole. The decreases (increases) in value of the investments are equal to the decreases (increases) in value of the technical provisions. However, when there is a mismatch, the insurer runs market risks.

Market risk is the risk of decreases in value by changes in the market variables such as interest rates, share prices, exchange rates, real estate prices and the like. This also includes asset and liability management (ALM).

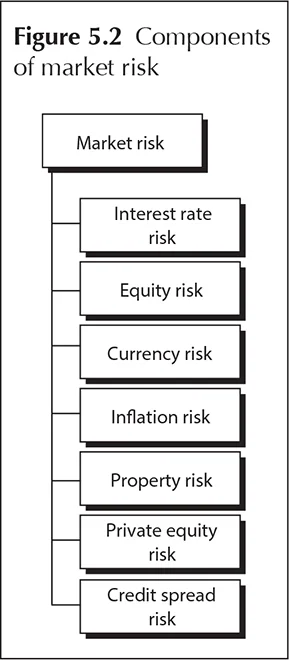

We can divide market risk into several subcategories, parallel to the market variables (interest rates, equity prices, foreign exchange rates, etc). This classification depends on the investment portfolio of the insurer. Below are a few commonly used sub-categories.

Interest rate risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in the interest rates. Matching is of particular importance here, as the interest rate has an effect on the value of both the assets and the liabilities.

Equity risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in the equity prices.

Currency risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in the foreign exchange rates. This is also called foreign exchange (FX) risk.

Inflation risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in the inflation expectations.

Real estate risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in real estate prices. This is also called property risk.

Private equity risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in the private equity markets. Although private equity is, in fact, a component of equity risk, it is considered separately due to its specific character.

Credit spread risk

The risk of decreases in value due to changes in the credit spread. The credit spread is an extra compensation as a part of the interest rates of corporate bonds on top of government bond interest rates. As such, this gives a reflection of the capital market’s general sentiment of corporate bonds. Chapter 7 will highlight that the credit spread played an important role during the financial crisis, both the bond credit spread, but also the credit spread on a number of government bonds (such as Greece). Credit spread risk is sometimes incorrectly seen as a component of the credit risk. However, the credit spread risk is determined by capital market sentiment and not by the situation of one individual counterparty, such as credit risk.

Interest rate risk is an important market risk category because interest rate changes impact both assets and liabilities. Interest rates have impact on the value of bonds and other fixed income securities because they are their major value driver. Also, they have an impact on insurance liabilities as many insurance products include guaranteed returns (ie, a fixed guaranteed interest rate). This effect is easily explained: in the valuation process future policyholder benefits are discounted (NPV) by a discount rate, ie, an interest rate. If interest rates increase, the value of liabilities decreases, which is positive for the insurance company, assuming that assets do not change. As indicated, assets values do change when interest rates fluctuate. If asset values do not change in tandem, the insurance firm as a whole may face a loss (or profit).

Generally, products with a longer duration are affected more by interest rate changes. This holds for both assets and liabilities. For most of the life insurers, the duration of the assets is lower than the duration of liabilities. Hence, an interest rate decrease results in a decrease of total value. In addition to this, many insurance products include all kinds of embedded options and guarantees: for example, settlement options that allow clients to choose between a lump sum benefit or annuity or lapse/surrender options that allow policyholders to cancel the policy in advance of the maturity date. Obviously, the minimum guaranteed rate is itself an important option. These characteristics are extremely sensitive to interest rate changes. As a result, the value of an insurance portfolio does not change proportionally to interest rate changes (this phenomenon is called convexity).

Normally, the interest rate curve has an upward slope: 10-year rates are higher than five-year rates. A parallel shift in the yield curve keeps the slope intact, eg, both 10-year and five-year rates change with 100 basis points. However, in practice yield curves do not always change in a parallel way. In an extreme (but absolutely not theoretical) instance, the yield curve can be flat (equal interest rates for all maturities) or even inverse (higher rates for short maturities). Many of these interest rate changes occurred during the financial turmoil that started in 2008.

These interest rate changes can have real impact on insurance companies, depending on the mismatch position. A prominent example of interest rate risk is the failure of the Japanese company Nissan Mutual Life in 1997. At that time, the company had 1.2 million policyholders and roughly US$17 billion of assets. Nissan Mutual Life had sold guaranteed annuities of up to 5.5% without hedging the interest rate risk. During the low interest rate period in the 1990s, the company faced enormous difficulties in honouring the guaranteed rates. Finally, the Minister of Finance had to close the company, resulting in the first insurance company bankruptcy in five decades. Total losses amounted to US$2.5 billion. Other examples exist as well, since many insurers faced high losses due to the low interest rate environment after 2008, when investment strategies were unable to meet the guarantees issued at policyholders. Chapter 7 will explore the impact of the financial crisis on insurers in more detail. However, it has already been mentioned that many insurers faced extreme losses due to the turmoil in the global financial markets. This is called market risk.

CONTROLLING MARKET RISK

The most important instrument for controlling market risk is creating a good investment plan, in line with the analyses of the ALM department. Often there are several investment plans. The strategic investment plan indicates how much market risk the company wants to take, what the allocation (in terms of percentage) to the different asset categories is (fixed income, equity), what the maximum mismatch can be, etc. In the tactical investment plan, different sectors are chosen: geographical, business sectors and so on. Similarly, the actual investments are indicated in the operational investment plan: individual bonds and shares.

ALM contains two components. First, ALM stems from an analysis of the profile of insurance liabilities. The ALM department derives the cashflow pattern of the insurance portfolio from the production systems, the emphasis thereby being on outgoing cashflows and benefit payments to clients. Second, ALM works out a strategic investment mix that meets the preconditions such as a maximum mismatch, a minimum solvency to be maintained and a maximum risk exposure (in terms of economic capital). Another term for ALM is ALM study, a periodical investigation of these two components.

We have already indicated in Chapter 4 that profit sharing is an important instrument for controlling risks. While initially developed as a commercial tool to attract more customers by providing additional return on top of the guaranteed rate, participating contracts are also a useful instrument for mitigating part of the market risks to clients.

Although a mismatch can be undesirable, insurers often deliberately choose to create one in order to generate additional return. That this also involves an additional risk needs no further explanation, and controlling this risk is the key duty of the investment department.

In practice, most insurers outsource the day-to-day management of the investment policy to (internal) asset managers. These parties then receive a mandate that gives them the freedom to operate with the aim of maximising the investment return. Naturally, the ALM insights (strategic investment mix, based on the ALM studies) constitute the preconditions of the mandate. There are also limits for certain asset categories, as stipulated in the investment plan.

PANEL 5.1 TWO MATCHING PRINCIPLES

Matching is the process of aligning the asset portfolio to the profile of the insurance liabilities, ie, technical provisions. This is to ensure that the insurer can have at its disposal the cashflows from the asset portfolio when cashflows are needed for the underwriting and claim processes. By doing so, the objective is also to align asset returns and client return requirements, including the risk sensitivities of the two. There are basically two principles for matching investments and liabilities. In cashflow matching, assets are chosen for which the cashflows exactly follow the cashflows of the insurance liabilities. A 10-year annuity is matched to a bond with a 10-year maturity. Cashflow matching is generally considered the “safest” strategy, but it is not possible for all products. Guaranteed returns or profit-sharing are, for instance, difficult to match using the cashflow matching principle. A major obstacle to cashflow matching is the uncertainty in liabilities due to underwriting risks. Also, in cases where cashflow matching is possible, it might not be desirable. Cashflow matching reduces financial flexibility for the insurer to pursue potential investment opportunities that arise – for instance, because the company has certain interest rate expectations.

Duration matching is more value-based, rather than focusing on each of the individual cashflows. In duration matching, investments are found where the interest rate sensitivity of investments and insurance liabilities is identical. When the interest rates change, investments and liabilities experience the same effects and the consequence for the insurer is nil on balance. Therefore, this strategy is also called immunisation. The central risk measure is the modified duration, which indicates to what extent an instrument decreases in value if the interest rate increases by 1%. A bond with a modified duration of 5 decreases by 5% in market value when the interest rate increases by 1%. However, this measure only holds for smaller interest rate changes.

In the investment mandate, certain “benchmarks” are often referred to. For each investment portfolio, it is indicated which benchmark needs to be followed, for instance, the FTSE index or MSCI index. There are many composed indexes that can serve as a benchmark for the asset manager. The “tracking error” indicates to what extent the investor deviates from their benchmark. As the asset manager specialises in investment, they also dispose of a detailed risk management system. The establishment and monitoring of limits and tracking errors are also included in the systems. This means that the investment manager has to rebalance the portfolio as soon as the difference between the actual portfolio and the benchmark breaches a certain threshold, the maximum tracking error. In some cases, rebalancing is done relatively quick and simple, whereas in other cases it may be impossible (whenever the market does not allow to sell or buy at a certain cost). Also, it may be undesirable to rebalance directly, for instance, when there is an intentional strategy to deviate temporarily from the general market. Economic capital plays a similar role in the entire investment system of the asset manager, since it can also serve as a general limit to the risk portfolio.

PANEL 5.2 INSURERS AND OPTIONS

Options are a very important component of ALM. Not so much because insurers invest a lot in options, but because (mainly, but not only, life) insurance products include many option-like constructions: embedded options. These include interest rate guarantees, repayment options and unconditional profit sharing and bonuses. At the time of issuing an insurance product, options may seem worthless. However, during the often long term, options can definitely reach high values. The interest rate sensitivity (duration) of these embedded options is often high, and therefore they deserve special attention from the ALM department. Only since the early 2000s, options have received attention, both from a practical as well as an academic perspective. Before that, awareness that guarantees included risks was relatively low. Also, the guarantees were badly recorded in the underwriting systems and databases. Therefore, insurers were unaware that options actually existed, let alone that they might/should be attached values before the time of claim payments. The fact that life insurance products (and hence the guarantees) have a long time to maturity makes an option even more costly in terms of risk and capital. We will see in the remainder of this book that Solvency II also pays explicit attention to embedded options.

MEASURING MARKET RISK

In the past, the tracking error was the central risk measure, and the difference between the actual investment portfolio and the benchmark was specifically observed. Nowadays, there is more emphasis on the mismatch between investments and insurance liabilities. The total (fair value) balance sheet of the insurer is central to measuring the mismatch of assets and liabilities valued using market-consistent methods (ie, fair value). For insurance liabilities in particular, the calculation of the market-consistent value is complex, because the accounting system is not based on fair value. Embedded options are also explicitly identified and separately valued in the risk management system.

In the market-value balance sheet, capital is the closing gap between insurance liabilities (ie, technical provisions) and assets. Simple scenarios for interest rates, equity prices, foreign exchange rates or other variables can be created with special software. Two types of scenarios are involved: historical and simulation scenarios. Historical scenarios, which are developments that actually took place, display the possible consequences for the present balance sheet: eg, what would happen if the stock market crisis of 1998 took place again? And what would the balance sheet look like in such a situation? A similar exercise is running imaginary scenarios: a set of events that are likely to occur but not identical to something that happened in the past. Before the 2000s, it was considered to be unlikely that interest rates would be low in periods in which assets returns were also low (classical economic theory). This could be an imaginary scenario. Also, a 10-year period of extremely low interest rates and market illiquidity is an example of this. Again, the insurer identifies the effect on current and future balance sheets and the potential risk measures to take. In scenarios based on simulations, statistical models are used to estimate, eg, the future interest developments based on current knowledge of the interest rate structure. From the recent history, a probability distribution for the entire future yield curve and other risk parameters is extracted. The simulation works similarly to the simulation described in the previous chapter: from the probability distribution, the model draws 100,000 observations (eg, 100,000 times a potential yield curve) with which the balance sheet is recalculated. Using this outcome, the simulation basically generates 100,000 potential future balance sheets. This is really a new probability distribution of the balance sheet from which conclusions can be drawn regarding risk vulnerability and sensitivity.

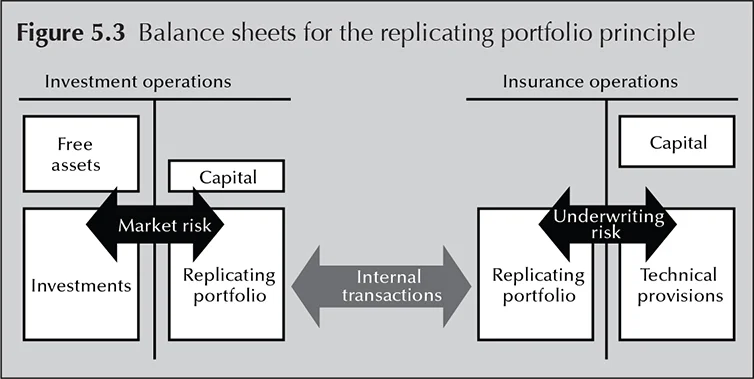

PANEL 5.3 REPLICATING PORTFOLIO

A specific technique is the principle of replicating portfolio. In this principle, an imaginary investment portfolio is created that is identical to the insurance liabilities (ie, the technical provisions), without taking the underwriting risks into consideration. The technical provisions are actually replicated with an imaginary asset portfolio, specifically consisting of bonds and options. The market risk is measured by the effects of interest rates, equity or other scenarios applied to both investment portfolios: the actual asset portfolio and the replicating portfolio. As both portfolios consist of known investment instruments, there are standard methods available to value them. When, in a certain scenario – for instance, an interest rate scenario – the two portfolios equally increase or decrease in value, there is no market risk for that market variable. When the portfolios do not increase or decrease identically, there is a market risk.

ECONOMIC CAPITAL FOR MARKET RISK

In order to establish the economic capital for market risk, the replicating portfolio and statistical simulations methods are used. In the replicating portfolio method, the risk manager creates an imaginary investment portfolio generating exactly the same cashflows as the insurance liabilities. Underwriting risks are not taken into account, and the calculation starts from the expected mortality rates and the claim amounts. In this way, the risk manager separates the underwriting risk from the market risks.

The next step in the calculation is generating scenarios. There is a separate scenario for each risk component, such as interest rate risk, equity risk, etc. Statistical models are developed to generate scenarios. In the field of interest risk especially, there are widely accepted statistical models where the risk manager only needs to estimate the parameters on the basis of historical interest rates. These statistical risk models can simply extrapolate a possible future interest rate curve multiple times from the present interest rate curve – for instance, 100,000 times. For each risk component there is a separate model, which in turn generates scenarios. Some software packages even perform combined analyses.

The total model determines the value per scenario of the replicating portfolio (for instance, 100,000 times per risk component) and the value of the actual investment portfolio. The difference is the value of the equity capital, projected one year ahead. With all these possible future values of capital, the insurer can make a statistical probability distribution again. It is most probable that capital will increase in value in one year’s time, but there is a small probability of the capital of the insurer dramatically decreasing in value.

In this probability distribution, the desired confidence interval and, hence, the worst-case value can easily be read off. For instance, a desired rating of A+ equals 99.95%. With 100,000 observations, the 99.95% confidence interval is the 50th observation if they are ranged in ascending order. The expected value (best estimate) is the middle observation. The economic capital is then calculated from the difference between the expected (best estimate) value and the worst-case value (see Figure 5.4).

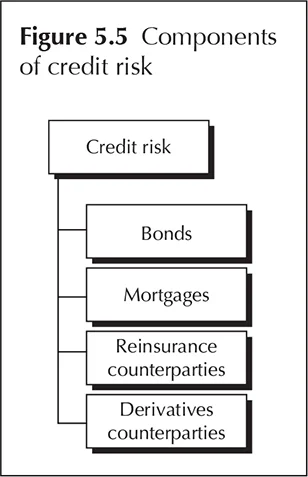

WHAT IS CREDIT RISK?

Apart from fluctuations in financial markets as a whole (market risk), the investment portfolio is obviously also sensitive to the state of individual assets. When one certain investment is not repaid, the insurer suffers a loss immediately. This is most obvious for bonds, which make up a significant part of the asset portfolio. When a bond issuer does not repay the bond at maturity, a direct loss arises. However, bond values also change when the issuer is downgraded due to changes in the ability to repay the loan. Other credit risk exposures in the investment portfolio arise with derivatives, because the counterparty in the derivative transaction also needs to honour the obligation when due. This is called credit risk.

Credit risk is the risk of decreases in value when counterparties are not capable of fulfilling their obligations or when there are changes in the credit standing of counterparties.

The investment portfolio of insurers consists largely of bonds. Should they be only government bonds, the insurer would run no credit risk: it is certain that the bonds will be repaid at the end of the maturity. Most western governments are considered very solvent, and hence perceived risk-free. The governments of emerging markets are, however, less solvent. For instance, during the 2002 crisis in Argentina, the government defaulted on its interest payments and repayment of the government bonds. Another example is the government bond crisis, where the market had serious doubts that a number of European governments would be able to repay the bonds due to high budgetary deficits (see Chapter 7). Greek government bonds were especially under stress, with discussions about either a full default or partial restructuring. In both cases, investors would lose. In the end, the Greek government decided in 2012 on partial restructuring, only granting partial repayment and extended maturity to all bondholders while at the same time restructuring the Greek economy.

However, in order to obtain a higher return, insurers also invest in corporate bonds that involve more credit risks: a corporate could fail to pay its interest payments or repayments or even both, which would saddle the investor. To compensate for such risks, the interest on corporate bonds is higher than on government bonds. Corporate bonds mostly account for the largest part of the total credit risk of the insurer, even though the balance sheet consists of only a smaller part of corporate bonds.

A further source of credit risk is the mortgage portfolio, another important component in the investment portfolio. In the life insurance industry in particular, mortgages are often granted in conjunction with life insurance. A mortgage is a loan where real estate property is taken as collateral. It often involves individuals, with a house as the pledge, but it can also involve commercial real estate, such as offices and shopping areas. As the collateral has sufficient value, the credit risk is restricted. If the mortgager (ie, the client) is unable to repay, the mortgagee (the insurer) has the right to sell the house. At times of high increases in the property market, such as during the late 1990s and early 2000s, the credit risk on mortgages was considered almost nil. In the late 2000s, credit risk on mortgages increased in some markets; contributing to this was the decrease in housing prices, and as a consequence house owners could not repay their mortgages.

However, when property prices decrease, as could occur as a correction to a real estate bubble, credit losses can take place in the mortgage portfolio. For instance, after a period of growth US housing prices decreased during the late 1990s and then exploded again in the early 2000s. Another example of real estate price corrections was in the Japanese market, where just before the turn of the century about US$20 trillion of property value was erased in Japan: some private property prices decreased by 90% after a couple of years and some commercial real estate property top locations even decreased by 99% in value. Also in Europe, housing prices decreased as a result of the financial crisis, but the impact differed per country and region. While German housing prices only dropped a couple of percentages in 2012, Spanish housing prices dropped consistently after 2007, with percentages well over 10% per year, and UK prices dropped in 2009 by over 20% on average.

Reinsurance can also be a source of credit risk. It could be that a counterparty in a reinsurance contract cannot fulfil its obligations at the moment when the money is actually needed – for instance, after a catastrophe. The loss from a catastrophe can be enormous, as can the credit risk. In addition, insurers are more often using derivatives to cover and hedge risk positions. It is important to guarantee that the counterparty in the derivative contract will pay up when necessary. The insurer also runs a credit risk here, meaning the risk that the counterparty may not comply with its obligations.

Credit risk is sometimes also related to the insurer’s risk of clients who do not pay their premium. Strictly, clients are not insured when they do not pay any premium and the insurer does not have to pay compensation when there is a claim. There is no credit risk either. In practice, insurers are fair when defaulting clients are involved; therefore, the debtor administration keeps close track of the payment delays. As the individual amounts are often much smaller than the credit risk in the bond portfolio, mostly no economic capital is calculated for this risk. Another type of credit risk occurs in the case of brokers, agents and other intermediaries that need to transfer premiums received from clients to the central bank accounts of the insurer.

The components of credit risk that were discussed here are represented in Figure 5.5.

CONTROLLING CREDIT RISK

As with all risks, spreading is the key to credit risk control – and it applies to all components of credit risk. The bond portfolio is a widely diversified portfolio. There are limits for individual counterparties, geographical regions, rating categories, business sectors, etc. These are stipulated in the investment mandates and also thoroughly controlled by the asset manager. As such, a concentration of the credit risk is prevented.

The same applies to the reinsurance policy. For instance, it will state limits for spreading by the reinsurers involved and the maximum coverage per reinsurer. For that purpose, credit rating is often used. In addition, the reinsurer is thoroughly analysed before doing business. Collateral is the instrument that is used to control the credit risk on mortgages; it is an extremely efficient instrument, as losses on mortgages are almost nil. Collateral is also used in certain reinsurance contracts.

MEASURING CREDIT RISK

The set of instruments for measuring credit risk is highly developed within the banking industry. This is necessary, as banks grant private credits that cannot simply be traded. This is very different for insurers, who have predominantly liquid marketable bonds and mortgages in the portfolio. This means that insurers, more than banks, will be subject to small changes in the financial position of the counterparty. An insurer will then sell the bond, whereas a bank does not have that possibility for private loans.

The credit rating is central to measuring credit risk. A selected number of major international agencies judge the financial solidity of market parties and publish their judgement through a type of report called a rating. These rating agencies base their judgement on a variety of information on the company: financial ratios, profitability, solvency and liquidity, as well as more qualitative aspects such as market position, client groups and management quality. The most well-known ratings are provided by the rating agencies Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) (see Figure 5.6). Other rating agencies are Fitch Ratings, AM Best, Dun and Bradstreet and Dominion. The rating agencies publish different kinds of ratings. A difference is made between a rating for the enterprise as a whole (issuer rating) and the rating of an individual debt (debt rating). In the last category, a difference is again made between short-term and long-term debt.

The good thing about rating is that rating agencies review their ratings regularly, mostly every year. An insurer does not constantly have to keep an eye on the bond portfolio itself to see if it is still solvent. Rating agencies assess the credit quality of each individual bond in the portfolio. That does not prevent the insurer from using its common sense in investment decisions and during portfolio monitoring. During the financial crisis (see Chapter 7), but also before the importance and power of the rating agencies in the entire financial system became more visible, this was recognised as a problem. After all, financial participants structure their financial market products in such a way that it could qualify for a certain rating. Also, the rating is a trigger that determines the value of financial instruments to a large extent. Rating agencies received massive criticism during the crisis, when many financial instruments were downgraded. A delicate fact is, of course, that the companies that issue the investment pay the rating agencies to grant a rating, potentially creating conflicts of interests. In supervisory systems, the rating could determine the solvency requirement that an insurer (or bank) should set aside, both in Solvency II and Basel III (see later in this book). This urges that insurers should have their own separate view on the credit risk of counterparties, including a detailed credit analysis. That this could be translated into a rating only has advantages, since it provides a common language for market participants.

The credit rating is also translated into the probability of a counterparty defaulting within one year, called the probability of default (PD). An A+ rating is equal to a PD of 0.05%. Table 5.1 shows how ratings and PD are related.

| Agency | Ratings | ||||||

| Moody’s | Aaa | Aa | A | Baa | Ba | B | Caa |

| S&P | AAA | AA | A | BBB | BB | B | CCC |

| PD (in %) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 1.10 | 3.50 | 16.00 |

In the banking sector, three parameters are often used to measure the credit risk. For each parameter, statistical risk models are available, depending on the specific counterparty or loan.

Probability of default

Probability that the counterparty cannot fulfil its financial obligations, expressed as a probability percentage.

Loss given default (LGD)

The loss when the counterparty is defaulting, expressed as a percentage of the outstanding amount. If there is collateral, the LGD decreases.

Exposure at default (EAD)

The outstanding amount at the time of default of a counterparty, expressed as a currency. The EAD is usually the total notional of the loan, but not necessarily; eg, additional credit lines, current accounts, etc.

These parameters are central to credit risk models. Insurers would rather focus on the external ratings than on internally calculated PD, LGD and EAD. Internal parameters are also less important for the bond portfolio. However, for private loans, these parameters are relevant.

ECONOMIC CAPITAL FOR CREDIT RISK

There are two main methods available to determine the economic capital for credit risk. The first method is in line with the banking instruments, and calculates the “worst case” and the expected credit loss on the basis of the three parameters (PD, LGD and EAD) mentioned above. The advantage of this method is the concordance with the banking principles, which are well developed and widely accepted.

The expected credit loss is calculated by multiplying the three parameters by each other. The worst-case credit loss is determined by a square-root formula. In line with the definition, economic capital for an individual bond is the difference between the expected and the worst-case credit loss11 In the banking sector, this is called unexpected loss (UL). (see formula below). When establishing the economic capital for a bond portfolio, diversification is taken into account. The calculation of economic capital for reinsurance credit risk is specific. It is complex because the PD can be determined beforehand. However, the exact amount that is owed to a reinsurer is unknown: the amount of the claim due to the catastrophe is not yet clear. Hence, the EAD is often set at the total cover of the contract. LGD is related to collateral arrangements, just as in the banking example above.

The second method uses a simulation. The insurer creates risk models to determine the value of the bond portfolio and the three risk parameters (PD, LGD and EAD) are input. Additionally, the phenomenon called rating migration is taken into account. This is where the rating of counterparties can change from year to year. Through simulation, the model calculates the value of the bond portfolio in a large number of scenarios. On this basis, a probability distribution is derived (as also described in the section on market risk). The economic capital is then determined analogously: the difference between the worst-case value and the expected value.

WHAT IS LIQUIDITY RISK?

An insurer needs liquid assets (cash) to pay out the policyholder benefits. Simultaneously, it also receives liquid assets in the form of premiums. These two cashflows are mostly unequal. As liquid assets produce less return than investments in bonds, for instance, an insurer strives to have sufficient liquid assets available – not too many, but definitely not too little!

When an insurer suddenly or unexpectedly has to pay more benefits than expected, there could be insufficient liquid assets – for instance, after a heavy storm or the unexpected first snowfall of the year. The claims need to be paid as soon as possible, so the insurer must free up liquid assets by selling part of its assets, possibly at an unfavourable moment. This can lead to financial losses. Whenever the market is low at the time the insurer needs to sell assets, it will face a loss. But what if there is actually no demand at all for this type of asset at that time? The insurer may decrease its price even further, but that is completely ineffective: there are no buyers. This situation occurred in a number of ways during the financial crisis, as will be seen in Chapter 7.

The insurer naturally aims to prevent defaulting on its clients as much as possible. If the client does not receive the expected compensation because the insurer has liquidity problems, confidence in the insurance company could be in danger, even if it is solvent.22 A company is solvent if there is sufficient capital (ie, assets exceed policyholder liabilities) and is liquid if it can honour the claimable payments requested. Not all clients can distinguish this, which is understandable. If confidence is endangered, several clients could cancel their insurance, with disastrous consequences. Life insurance would have to be repaid immediately and, for non-life insurance, clients would demand part of their premiums. These consequences justify prevention of liquidity problems.

Liquidity issues in the financial markets usually happen when there are large financial market disruptions, such as natural disasters causing big insurance claims, downgrading of large companies and major unexpected regulatory changes. These may be based on facts, but also on rumours – financial markets are sensitive to new information and speculation. These could potentially create market disruptions and cash in- or outflows.

Another source of liquidity risk for insurers is policyholder surrenders (also called lapse). When many clients cancel their life policy, the insurer is obliged to pay the surrender value, as specified by the policy conditions. However, the funds were invested in long-term assets. Liquidation of those assets will be costly, especially if the surrender occurs in larger volumes. This is why product design has clear liquidity consequences, and vice versa.

Finally, liquidity risk occurs when mass claims arise out of a large-scale event, often weather-related such as floods, hailstorms or windstorms. The direct insurer wants to pay the clients directly. However, the settlement of the claim with the reinsurer might take a longer time. This could involve liquidity issues for the direct insurer.

In addition to equity capital, a number of large insurers issued subordinated bonds to serve as a buffer to absorb losses. These bonds have a certain maturity and, for shorter maturities, the insurer may assume that they are rolled over quite simply: a bond at maturity is repaid with the proceedings from a new bond. This happens not only with regular subordinated bonds, but also in complex securitisation transactions. What would happen if there is no appetite for the new issued bond in the market? The insurer will need to repay the first bond, without having the new bond available. In other words: the insurer will need to have liquid assets at hand to withstand this.

This has highlighted a number of important issues:

-

- liquidity and solvency are not identical – a perfectly solvent insurance company may have large liquidity problems;

-

- timing of payments is paramount for facing liquidity risk;

-

- market sentiment plays a big role in liquidity risk; and

-

- liquidity risk not only impacts assets, but also liabilities.

We define liquidity risk as follows.

Liquidity risk is the risk of unexpected or unexpectedly high payments, where complying with the liabilities involves a loss.

For a bank, the liquidity risk is much more dominant than it is for insurers. Bank deposits are claimable33 Additionally, the banking system includes a “lender of last resort” (often the central bank), from which banks can immediately borrow liquid assets under conditions in case of a liquidity crisis. on demand for a large part, as opposed to the technical provisions of the life insurer. The insurance liabilities of non-life insurers could suddenly have to be paid. For insurers, being less strongly intertwined than banks, there is less probability of the problems of one insurer having spill-over effects to another insurer.

We can distinguish market liquidity risk and funding liquidity risk. Market liquidity risk is the phenomenon that less liquidity is available in the market. This could be because there is no appetite to buy or sell assets. As a consequence, the insurer needs to find access to different funds to honour payments in order to prevent default on these payments. Often it relates to different assets. Funding liquidity risk is the phenomenon that an insurer cannot roll-over its assets or liabilities (mostly liabilities). Consequentially, assets need to be freed up to fill the gaps or other liabilities need to be defaulted on. Ultimately, the liability holders are at risk here. Often, market liquidity problems exacerbate funding liquidity problems. Conceptually, there is no difference between the payment of a claim to policyholders when due and an interest/principal payment to investors. However, the impact of harming policyholders is mostly considered to be greater than for investors. Besides, contracts with investors could potentially have clauses regarding subordination.

How is liquidity risk managed within the insurance company? The treasury department monitors cashflows on a day-to-day basis, and uses liquid assets as efficiently as possible in the form of short-term and liquid investments. The treasury department identifies the liquidity of each balance-sheet item, both now and on future dates (eg, 12 or 24 months ahead). For each balance-sheet item, it is assessed how liquid it is by the capital markets and whether or not (un)expected payments could arise. This is not only done per balance-sheet item, but also per so-called time bucket. Time buckets are separate time intervals, such as one month, 2–3 months, 3–6 months and so forth. The more time buckets are used, the more precise the predictions and analyses, but also the more complex the methodology gets. The entire analysis includes claim behaviour, but also lapses and prepayments. It is also important whether future cashflows can be expected to arise from current contracts. Also, payments due to operational costs (salaries, office rents) are taken into account. Financial contracts, such as derivatives, securitisations or special funding structures, could include so-called triggers that cause additional payments. A simple example is a derivative transaction where more collateral is required. Naturally, this process results in a large liquidity buffer to pay out unexpected non-life claims. In general, there are liquidity limits to the asset portfolio.

Of course, a way of addressing liquidity risk is holding a liquidity buffer as part of the assets. In times of stress, however, this might not be sufficient. Another potential means of generating liquidity in times of stress is through contingent liquidity – either contingent capital or loans. This is a very important tool to manage liquidity risk. Contingent liquidity is a financial contract that enables a company to access financial resources in times of crisis. An example is a contract where a third party supplies additional capital or a subordinated loan after the solvency ratio drops below a certain level. A banking credit line is another simple example. It is critical to arrange these contracts in non-crisis situations, because during a crisis investors are normally less prepared to provide funds. This was also seen during the financial crisis that started in 2008 (see Chapter 7), when companies in financial problems could not access the capital markets for funding or capital. Governments finally had to bail out a number of institutions, including the world’s largest insurer at that time, AIG.

Measuring liquidity risk is not that simple. In the insurance industry, there are no standard measurements for liquidity risk. Nor is economic capital calculated for liquidity risk. The reason is that economic capital is focused on the solvency position. Previously, it was remarked that a perfectly solvent institution can also have liquidity problems. Some experts even stated that liquidity risk is much more dangerous than solvency risk (ie, all other risks). In other words: liquidity risk is either totally in control or totally out of control and life threatening. The underlying message is that liquidity risk can manifest itself via the joint occurrence of all other risks.

The well-known liquidity ratio from management accounting is defined as the ratio between liquid assets and liquid liabilities. For a healthy liquidity position, this ratio should be at least 100%, but preferably above that level. This simple liquidity ratio can be used in the insurance industry as well. However, more advanced liquidity analyses use the liquidity ratio per time bucket or time horizon. This makes the analysis forward-looking in order to prevent future problems. A variant of this applies weights to all items of the balance sheet in accordance to their liquidity. For instance, cash would receive a 100% weighting, as would liquid bonds, but mortgages would receive a lower weighting (50% for instance) to reflect their lower liquidity in case of problems. The same process should be done for liabilities. The liquidity risk indicator is the ratio of weighted assets over the weighted liabilities. The target is to have a minimum 100% ratio, but preferably with a little safety margin. This liquidity weighting process is also the basis for some rating agencies.

The size of the liquidity buffer is an important measure of liquidity risk, but more interesting is to run scenarios to assess the liquidity profile of the company under stress. This is similar to historical and imaginary market risk scenarios, except for the fact that the focus is on liquidity rather than solvency. Often during market crises, a shock in (market) liquidity arises. To that end, many potential liquidity scenarios are available to companies. It should also be noted that liquidity risk is closely related to other risks. Good management of other risks can prevent liquidity problems. This alone is not sufficient, however. Specific attention to liquidity risk is required, including a detailed liquidity analysis.

CONCLUSION

This chapter described the risks relating to the activities of insurers on financial markets. In market risk, the sensitivity to interest rates and equity prices is generally dominant whereas, in credit risk, the bond portfolio is the most important point of attention for many insurers. The chapter examined the origin of risks, and how they can be managed and measured. In the calculation of economic capital, a structure of simulation models was described. It concluded with a discussion of how liquidity risk differs from the other investment risks and how insurers address this. Chapter 7 will later describe how many of the issues discussed in this chapter manifested themselves during the financial crisis.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net