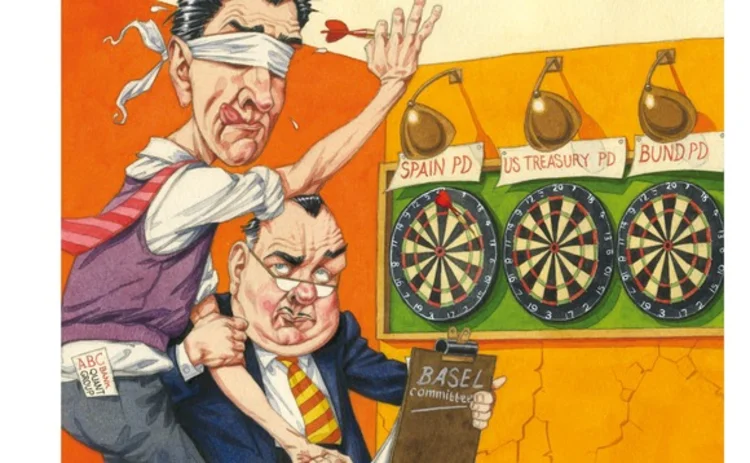

Basel 2.5 meets the Sarkozy trade: new rules could hit bond demand

Regulators want banks to hold more capital against government bond positions, but the regime is being changed at a time when the industry is the main source of demand for big eurozone issuers such as Italy and Spain. In addition, banks fear modelling difficulties could make the numbers meaningless. By Laurie Carver

It's known as the Sarkozy trade – using the cheap three-year loans doled out by the European Central Bank (ECB) in December and February to buy government bonds, particularly those issued by a bank’s own sovereign. According to ECB data released at the end of April, Italian banks added €67.5 billion to their holdings of eurozone government debt in the four months from the start of December to the

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Market risk

Repo and FX markets buck year-end crunch fears

Price spike concerns ease as September’s surprise SOFR jump led to early preparations for bank window dressing

Market risk solutions 2023: market and vendor landscape

A Chartis Research report that examines the structural shifts in enterprise risk systems and the impact of regulations, as well as the available technology.

The new rules of market risk management

Amid 2020’s Covid-19-related market turmoil – with volatility and value-at-risk (VAR) measures soaring – some of the world’s largest investment banks took advantage of the extraordinary conditions to notch up record trading revenues. In a recent Risk.net…

ETF strategies to manage market volatility

Money managers and institutional investors are re-evaluating investment strategies in the face of rapidly shifting market conditions. Consequently, selective genres of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are seeing robust growth in assets. Hong Kong Exchanges…

FRTB spurs data mining push at StanChart

Bank building “single golden source” of trade data in a bid to lower NMRF burden

Asian privacy laws obstruct FRTB data pooling efforts

Bank scepticism and regulatory hurdles likely to inhibit cross-border information sharing

Seizing the opportunity of transformational change

Sponsored Q&A: CompatibL, Murex and Numerix

Doubts grow over US FRTB implementation

Fragmented roll-out would price European banks “out of the market”