This article was paid for by a contributing third party.More Information.

The impact of European gas prices on climate goals

As governments increase their focus on climate change following the UN Climate Change Conference, COP26, ZE Power asks whether high gas prices in Europe could derail decarbonisation efforts

Record-high energy prices have taken their toll on industries throughout Europe – especially in the UK, where a raft of smaller power retailers have gone out of business in recent months. The steep increase in gas prices in 2021 has also lessened the incentive for many power plants to move away from coal, threatening Europe’s ability to meet its climate targets.

In this article, ZE Power presents an analysis of the situation, looking at the causes of high gas prices, the outlook for gas, coal and carbon prices, and the impact of the interplay between these on climate goals going forward.

Europe has struggled this year to import enough natural gas to refill its stores and run its power plants amid a global recovery from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Gas prices for next-month delivery at the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF), the regional benchmark, rose to record levels of more than €120 per megawatt hour (MWh) in early October, from €17.90 at the start of 2021, as regional suppliers sought to replenish storages ahead of the coming winter.

Soaring gas prices are also making electricity more expensive, particularly as more and more coal-fired plants are being shut down to help the bloc achieve its climate targets.

German baseload electricity for delivery in 2022 also leaped to more than €180/MWh in early October, after having started the year at €52/MWh. This sudden and steep increase caused mayhem in the market as traders faced huge margin calls on open positions, with many forced to dump their positions to remain solvent.

The rally reached a crescendo in early October, when prices were moving by as much as 30% within a single session, before Russian president Vladimir Putin appeared to trigger a widespread sell-off when he pledged that Russia would help moderate energy prices by raising gas supplies.

How did it start?

An extended winter heating season in 2020–21 left storages in Europe at their lowest end-of-winter levels since 2018, according to data from Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE), and stocks have not been replenished as quickly as normal. In August, gas storages in the European Union were at their lowest level for that time of year since 2013, GIE data shows. Even by early October, storages were still 20% lower than at the same time in 2020 and 2019.

Europe’s shortfall stems from a combination of declining local production, a squeeze on imports from Russia and strong competition for liquefied natural gas (LNG) from other regions.

According to the European Commission (EC), regional LNG production declined 11% to 13.8 billion cubic metres in the first quarter of 2021, compared with a year earlier, as output from Netherlands’ giant Groningen gas field declined ahead of its eventual decommissioning in 2022.

Consumption in Q1 rose 7.6% year-on-year to 141.8 billion cubic metres, while net imports dropped by 3% to 78.5 billion cubic metres. LNG supplies fell by 29% from the same period in 2020, partially offset by a 9% hike in pipeline supplies from Russia and a jump of 141% in flows from Algeria.

Imports drop

The largest single supplier of gas to Europe is Russia, which ships around half the EU’s imports.

While long-term contracted volumes remained broadly stable in the early part of this year, shorter-term spot sales declined sharply, reflecting rising market prices, according to the EC.

“Gazprom preferred to rely on withdrawals from its own storages in EU territories to supply its clients, given the average cost of injected gas was much lower compared to hub prices in Q1 2021,” the EC reported.

Russian gas is shipped to Europe via a network of pipelines across the Baltic Sea, through Belarus, Ukraine, the Black Sea and Turkey. Russian state-owned producer Gazprom is also leading a consortium of companies that recently completed Nord Stream 2 – a second pipeline across the Baltic Sea.

While the new pipeline is now ready, it cannot deliver gas to customers until it has received all relevant approvals and certifications from German, Danish and EU regulators – a process likely to last the rest of the year.

The European market has been closely monitoring the progress of the Nord Stream 2 project, which was originally scheduled to complete in 2020.

The pipeline is intended to boost the EU’s security of supply but has encountered stiff opposition from the US government, as well as Ukrainian interests, who see it as increasing Europe’s reliance on Russia.

Even though Nord Stream 2’s promoters say the project will complement, rather than replace, much of Europe’s existing supplies – including volumes that Russia has sent through Ukraine – the EC reported the volume of Russian gas transshipped through Ukraine plunged by 83% in Q1.

Trading sources reported that Gazprom declined to book additional pipeline capacity beyond its contracted commitments throughout Q2 and Q3, and has yet to agree a new long-term contract with Ukrainian pipeline owner Ukrtransgaz for shipments after 2024.

According to some analysts, Russia’s domestic stockpiles are also at unseasonably low levels, meaning potential export volumes are being diverted into Russian storages.

Analysts at Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS) estimated that, in April 2021 “[Russian] stocks were just 19% full, rather than the average of 39% as witnessed in the Aprils of 2017–19.”

The EU also imports significant volumes of gas through pipelines from Algeria, but a dispute between Algeria and its neighbour Morocco threatens to reduce supply from the south.

Growing tensions between Algeria and Morocco have led to delays in the two renewing an agreement for Algerian gas to move to Europe through the Gazoduc Maghreb–Europe (GME) pipeline, which runs through Morocco to Spain. GME passed into Moroccan ownership on November 1, and the existing transshipment agreement expired on October 31.

Algeria’s state-owned producer Sonatrach is now working to boost capacity through its own Medgaz pipeline to Europe by 25% before the end of this year. However, experts warn that even this increase will not fully replace the volumes lost through the GME pipeline.

LNG switches to Asia

In addition to pipeline gas, Europe has historically received a considerable volume of LNG from exporters in the US, the Middle East and Africa. However, the fast-growing market for LNG has led to more dynamic pricing, and European buyers now have to compete with Asian consumers for available supply.

Low stocks in Asia after last winter, coupled with rapid increases in demand, have led to spiralling price competition as buyers scour the market for available cargoes. Shipments of LNG from the US Gulf Coast, the closest source of the chilled gas to Europe, have bypassed the EU for much of this year in favour of higher returns in Asian markets.

As a result, Europe faces the coming winter with gas stocks at their lowest for a number of years, while demand has increased as more power is generated with the fuel.

What happens if gas stays tight?

We are already seeing the result of the gas shortage. Utilities are burning as much coal as possible to generate power to divert gas into storage for domestic heating through the winter.

Coal’s renaissance in the latter half of this year has also tightened that market, and prices have begun to jump as European buyers compete with other buyers such as China for available supplies. One German plant even ran out of coal supply and was forced to suspend operations in early October.

However, coal generation is shrinking as EU member states follow through on pledges to phase out use of the polluting fuel. According to the Beyond Coal campaign, at least 13 coal-fired plants were scheduled to close this year, as well as three German units that will shut in December after winning compensation in an April government tender.

Falling coal generation means some natural gas power capacity needs to operate at the margins, and it is these plants that are setting the high prices for natural gas and electricity in Europe at the moment.

The gas crunch couldn’t come at a worse time for the region’s leading economy, as the country also prepares to close three of its six remaining nuclear plants at the end of this year. Previous closures have led to brownouts and high electricity prices.

Poor renewable generation has also added to the problem. Data from the Fraunhofer Institute shows that German wind, solar, hydro and biomass generation in the nine months to September 2021 has fallen by 7% from 2020. Coal output has grown 22% year-on-year, while gas generation is down 8%.

Power and gas traders have all absorbed this and other data; prices for winter energy are at record levels and are likely to remain high through to spring.

Carbon’s role

While gas prices were soaring, EU carbon allowances nearly doubled in 2021, reaching a peak of €65.77 shortly before joining the energy market’s sharp sell-off. As a consequence of energy price moves, gas-fired electricity generation is now less profitable than coal, even after the increase in carbon prices.

Gas typically generates half as much CO2 as coal per unit of power generated so, as the price of natural gas rose far quicker than that of coal this year, the price of carbon kept pace to maintain gas primacy in the generation merit order.

However, this summer it became clear Europe needs more gas in storage rather than burning it for power. To ensure gas flowed to storage rather than power, gas prices had to rise sufficiently so coal became comparatively more profitable as an electricity fuel.

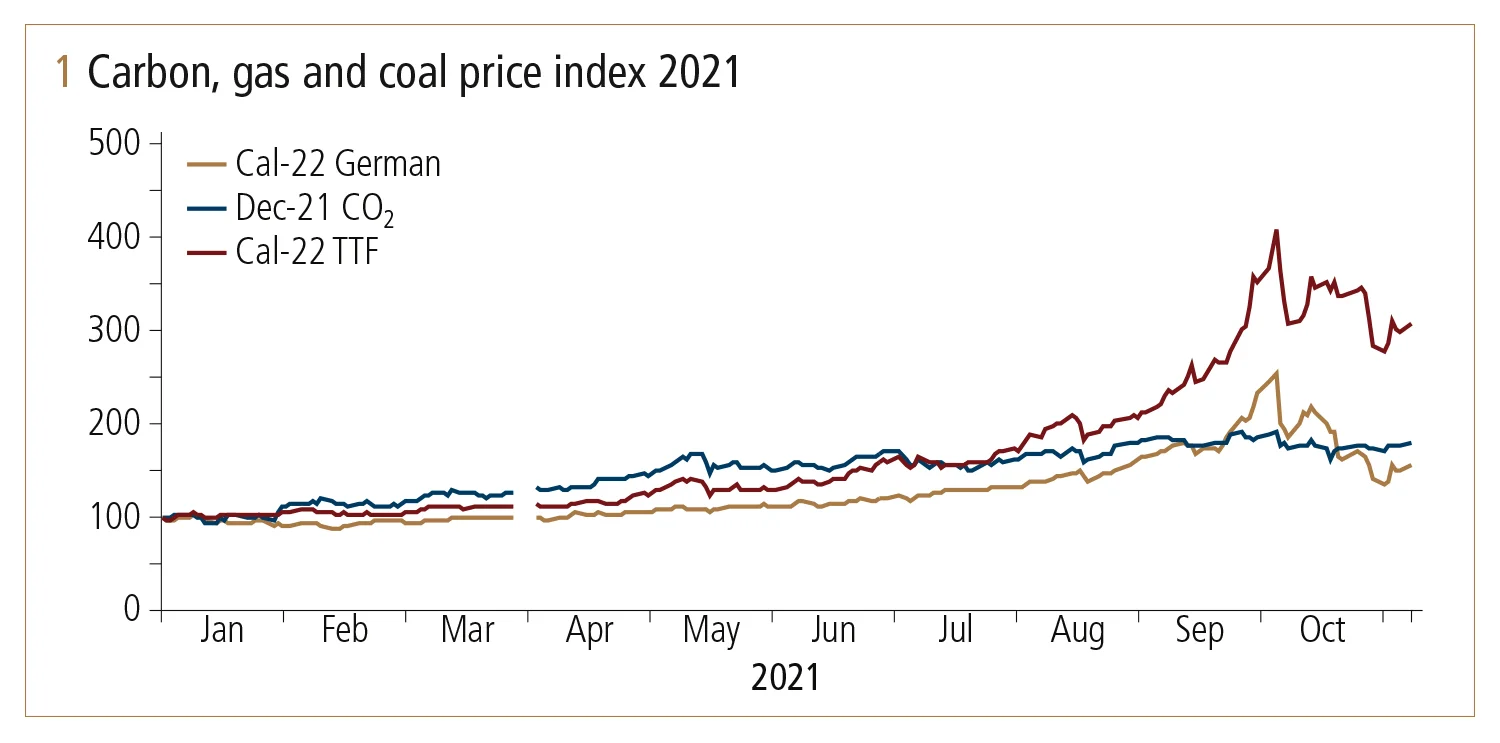

Indexing the market prices shows that carbon and gas prices began to diverge in July, as Dutch hub TTF prices began to rise very quickly and carbon rallied more moderately. In contrast, coal prices only began outstripping carbon towards the end of September (see figure 1).

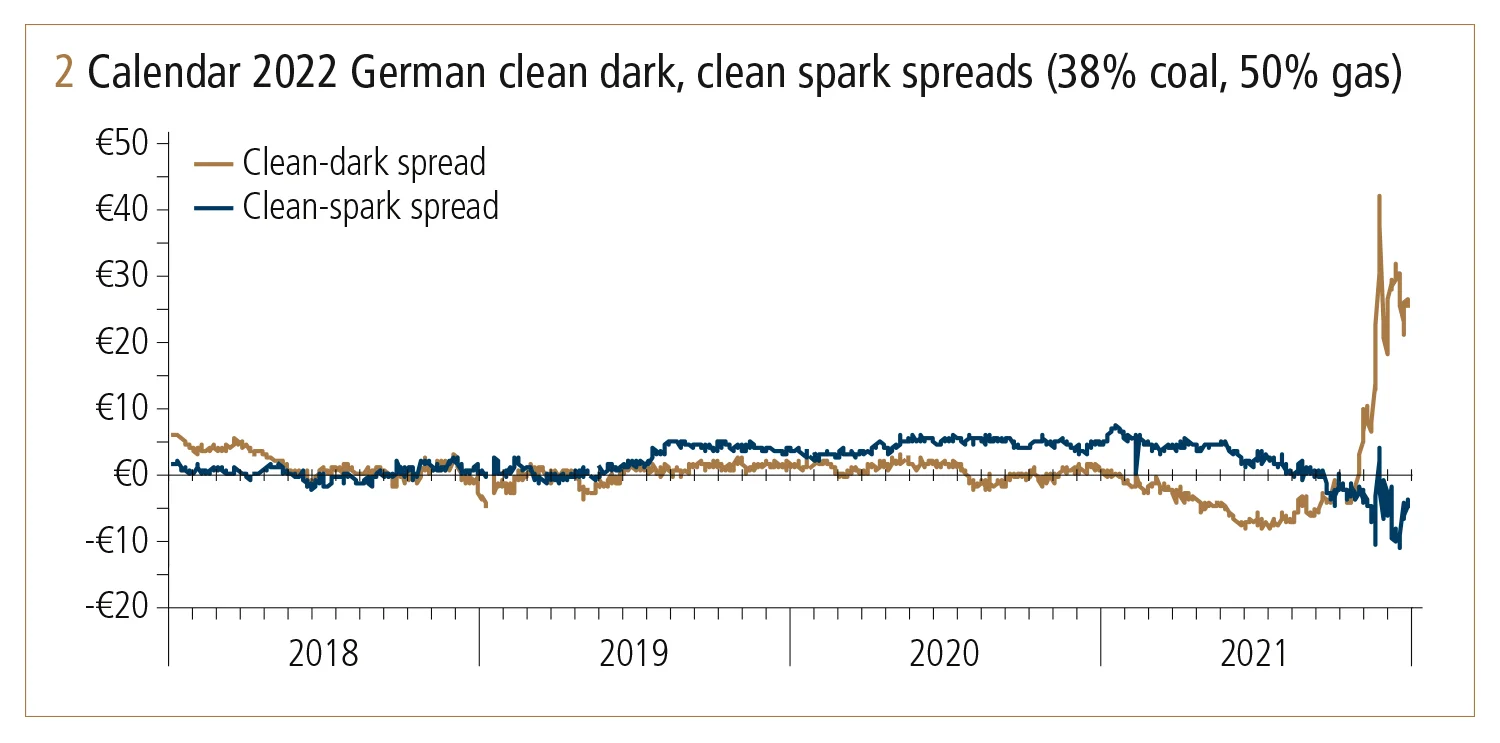

The price moves meant, for power generated next year, coal became more profitable than gas at the end of September – since then the so-called clean dark spread has jumped to as much as €42/MWh, while the gas margin, known as the clean spark spread, has fallen into negative territory (see figure 2).

What can the gas market do?

In the short term, the lack of supply may only be alleviated when Russian shipments increase, either by higher transshipments through Ukraine and other interconnectors, or when the Nord Stream 2 pipeline begins operation. Additional supply could come in the form of LNG, but this would require European prices to match or exceed those of Asia, which is currently receiving the lion’s share of available cargoes.

And the long-term balance is likely to remain tight as consumption in Europe is expected to continue to rise. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted 2021 demand would increase by 3%. However, the rapid growth of renewables is set to eat into gas’ growth potential, it adds.

“European gas demand is expected to remain stable through the period [2021–25],” the IEA said in a separate report. “The gradual phase-out of over 50 gigawatts of nuclear-, coal- and lignite-fired power generation capacity creates additional market space for gas-fired power plants.”

But gas’ growth “is limited by the rapid expansion of renewable power generation, set to increase by almost 30% over the medium term”.

And it won’t be just renewables that limit gas’ growth. Some analysts are predicting carbon permit prices in Europe to exceed €90 by the end of the decade, as the bloc tightens the limit on greenhouse gas emissions as part of its goal to cut CO2 by 55% from 1990 levels by 2030.

Higher CO2 prices will bring yet more low- or zero-carbon alternatives into play at the expense of gas, experts say, including hydrogen as a process fuel for steel-, cement-making and petrochemicals.

Long-range projections envisage a European economy in which natural gas has only a marginal role, but the experience of the past few months suggests that there are many more twists and turns before we get there.

Climate risk – Special report 2021

Read more

Sponsored content

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net