How Amazon and Netflix disrupted value investing

New business models have upset a common metric in the quant strategy

The disruption economy is upsetting one of the oldest systematic investment strategies.

Value investors buy unfashionable underpriced stocks and wait for them to come back into vogue with investors. The difficult part is distinguishing those stocks that are cheap for a reason from those that are just cheap. At its core, the strategy relies on frothy markets reverting to the mean.

Digital disrupters have thrown a spanner in those works and are an important part of the reason the strategy has done poorly in recent years. By wrecking old business models, companies like Amazon, Netflix and Uber have created a class of companies that are dying slow deaths and a class of winners that value strategies inadvertently ignore.

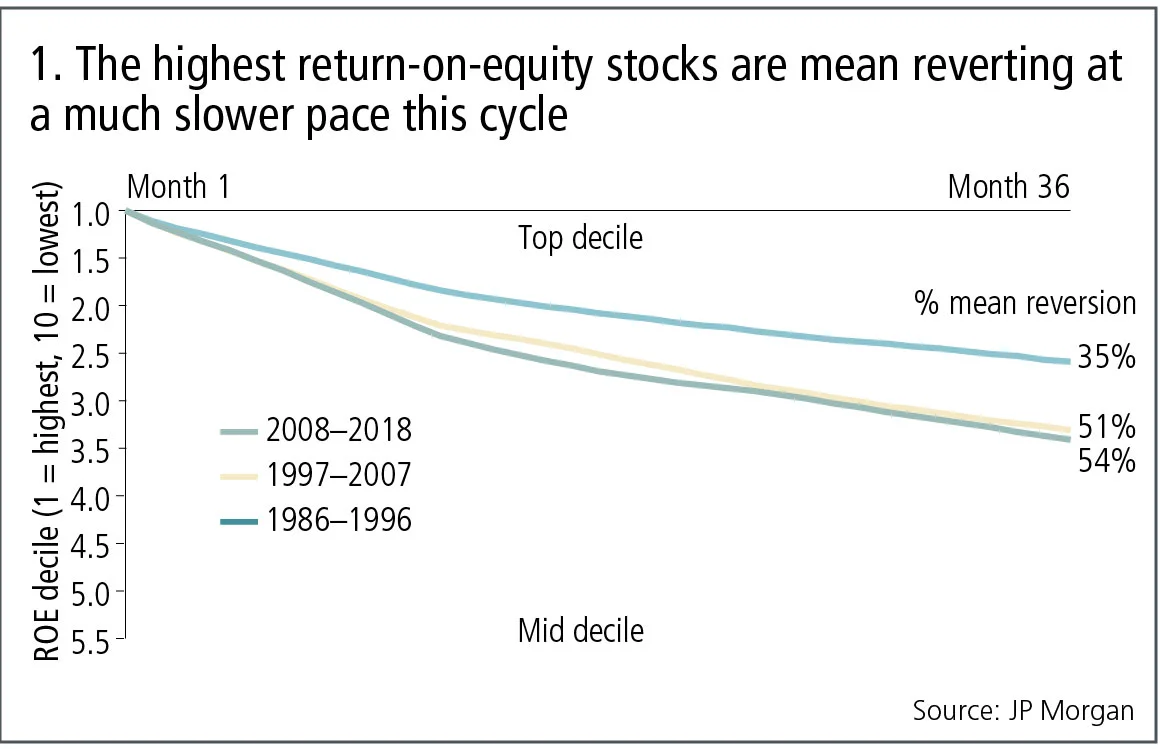

The effect is that mean reversion has slowed. Winning stocks are winning for longer and cheaper stocks are languishing for longer, too, creating a drag on the strategy (see figure 1). Dubravko Lakos-Bujas, JP Morgan’s global head of quantitative research, calls it a “winner takes all” economy. “The mean reversion story that we’ve seen play out in history over and over is still alive, but in this cycle it is taking a lot more time,” he says.

Lifetime bargains

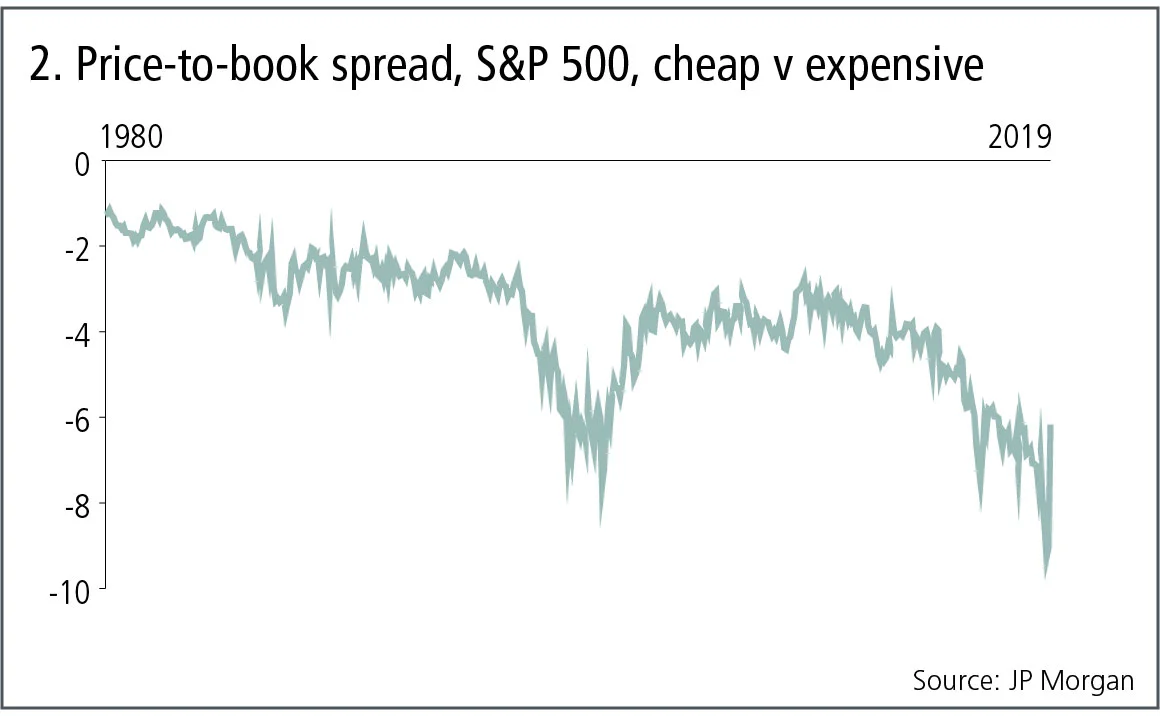

The irony here is that in one sense quant value strategies have seldom looked more attractive. Cheap stocks are close to the cheapest compared with rich stocks they have ever been (see figure 2). But the value trap created by disrupters calls for changes to quant thinking.

Price-to-book – the longest-standing and most common metric used to filter value stocks – “stands out as the big loser”, says Vitali Kalesnik, head of quant equity research at Research Affiliates.

This simple ratio of a company’s stock market valuation to the worth of its assets is more prone to selecting junky companies, ignores intangible assets and is oblivious to the quality of the enterprise. “In the current environment, it’s not a good measure,” as Kalesnik puts it.

An undervalued technology company with few tangible assets other than computers, desks and sharp-minded programmers, for example, scores a high price-to-book ratio. Value filters that rely too far on price-to-book will ignore such companies, along with a host of other key sectors. That is a special problem in the US, where service-based businesses dominate.

Partly, this should be no surprise. Price-to-book was conceived as part of an academic exercise. When Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, the architects of systematic value investing, developed and tested quant value strategies 30 years ago, they didn’t try to create the best approach for all environments and all eventualities.

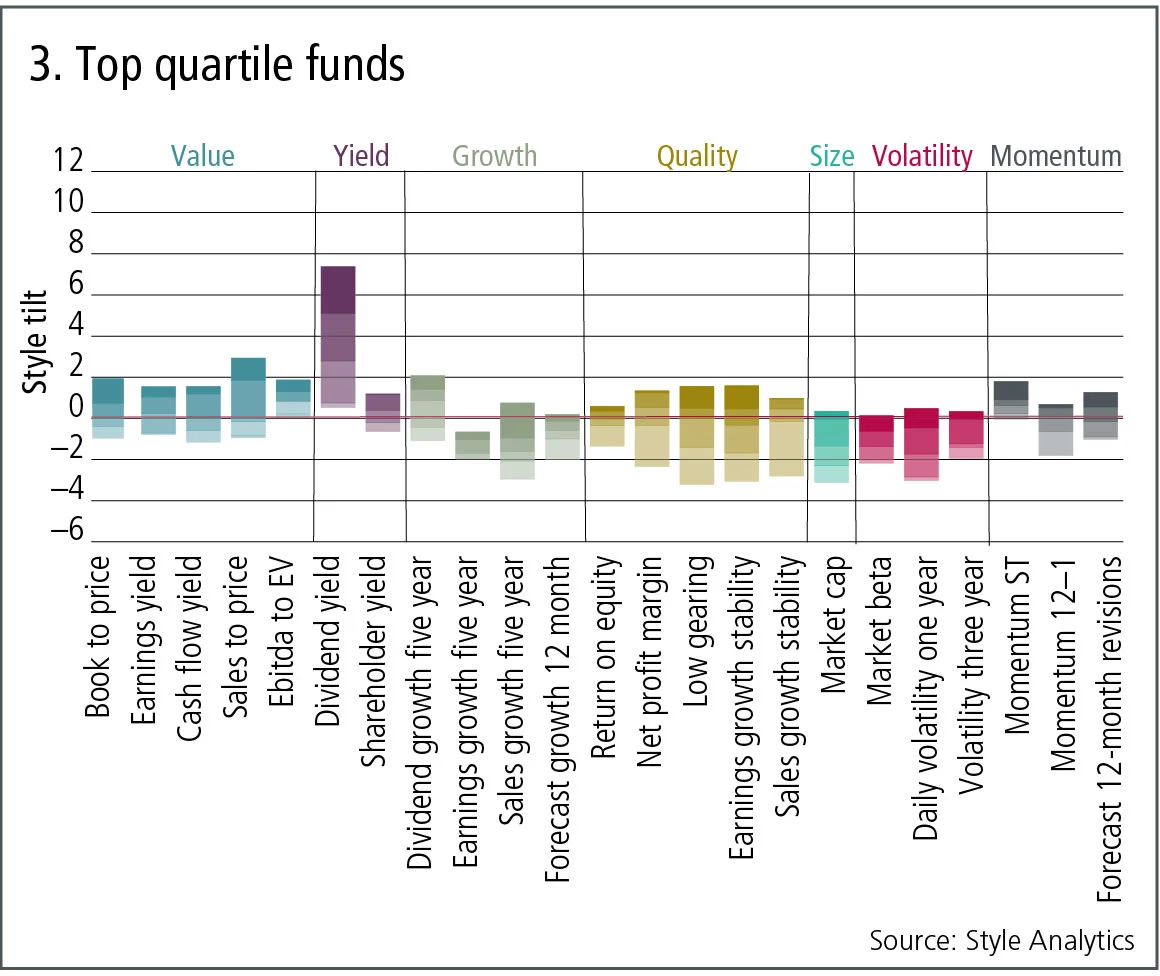

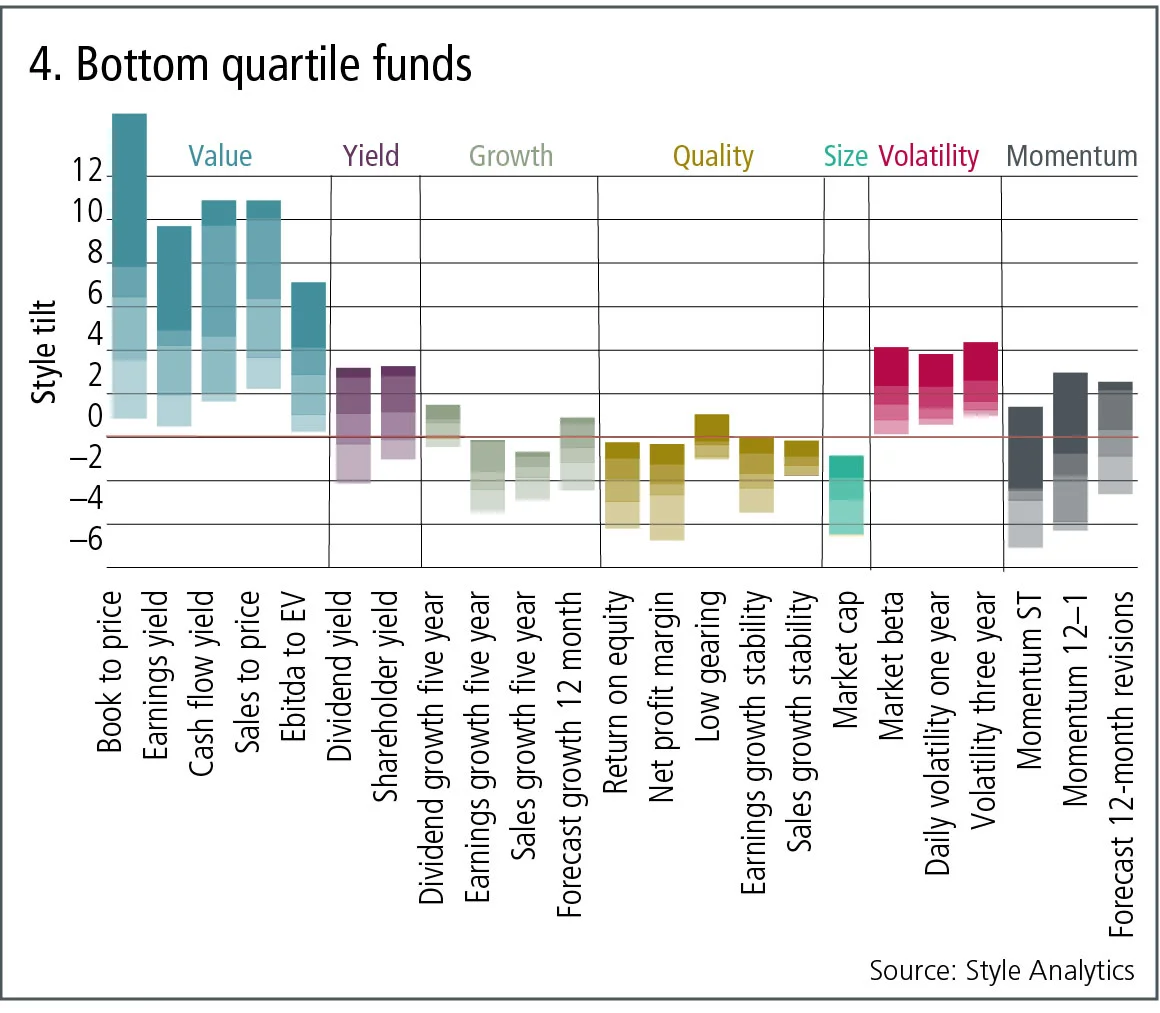

US value funds with an outsized tilt to price-to-book did especially badly in the last quarter of 2018 and first quarter of this year (see figures 3 and 4), according to Style Analytics, a provider of factor analytics. Funds that fared better tended to favour an alternative metric – high dividends.

That’s not to say quants should simply ditch price-to-book. For a start, it still works in some regions. In Europe, for example, where the manufacturing base is proportionally bigger, price-to-book remains more useful.

And other indicators have flaws, too. Dividend yield – the standout metric in the Style Analytics analysis – generally works well in Europe, but less well in the US where share buybacks are a popular way to return cash to investors.

One solution is to tailor the metrics to the markets and sectors where they are applied. Kalesnik advocates adding to quant models measures such as price-to-cashflow, -sales and -dividends over five-year averages. Doing so is a way to capture “quality companies that are also cheap”, he says.

Many quants see good prospects for a revival in value strategies, despite the drudgery of recent years. But the influence of Amazon and the like means quants must be careful about how they measure what they manage.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Our take

Fannie, Freddie mortgage buying unlikely to drive rates

Adding $200 billion of MBSs in a $9 trillion market won’t revive old hedging footprint

Degree of Influence 2025: Derivatives pricing dominates; quants don’t follow the AI herd

Rates and volatility modelling, as well as trade execution, top quants’ priorities

There’s a punt factor in stocks that investors might be missing

Speculative trading creates linkages between crypto and equities that vary depending on the stocks in question

Passive investing and Big Tech: an ill-fated match

Tracker funds are choking out active managers, leading to hyped valuations for a dangerously small number of equities

Sticky fears about sticky inflation

Risk.net survey finds investors are not yet ready to declare victory on inflation – with good reason

Why a Trumpian world could be good for trend

Trump’s U-turns have hit returns, but the forces that put him in office could revive the investment strategy

Roll over, SRTs: Regulators fret over capital relief trades

Banks will have to balance the appeal of capital relief against the risk of a market shutdown

Thrown under the Omnibus: will GAR survive EU’s green rollback?

Green finance metric in limbo after suspension sees 90% of top EU banks forgo reporting