A catastrophe waiting to happen?

As climate change and geopolitical uncertainty ratchet up the risk of a single, catastrophic event, insurers are turning to catastrophe bonds to offset that risk. Richard Bravo reports

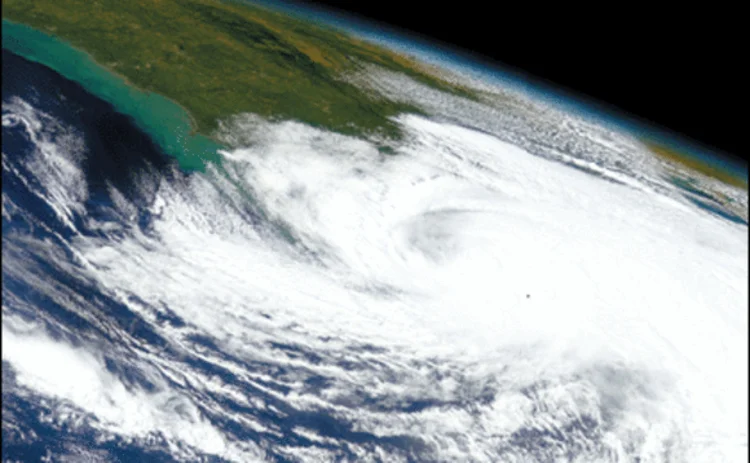

By the end of September, US Congress was contemplating additional funding – a possible $12.2 billion – to help the southeastern states recover from a severe start to the hurricane season. Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan and Jeanne wrought an untold amount of destruction on Florida, initiating the largest recovery effort ever by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The intensity of the weather pattern was something of an anomaly, this being the first time four hurricanes have hit the same state since 1886 when Texas was the unlucky victim. And while the magnitude of the destruction was felt by many throughout Florida and its neighbouring states, a band of speculators, whose investments are correlated to the level of destruction due to weather patterns, was breathing a sigh of relief.

The investment vehicles are called catastrophe bonds, and they have been set up in recent years allowing speculators to bet on disasters, which simultaneously creates a means for reinsurance companies to deflect a huge amount of risk. These risks can relate to terrorist events, wind exposure in Europe, earthquakes in California and, in this particular case, hurricanes on the east coast of the United States.

The birth of cat bonds, as they are known, came about following the huge losses suffered by the insurance industry after the devastation of Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Andrew, a category-four hurricane that hit the Florida coast in mid-August, was the most expensive natural disaster in the history of the United States, causing an estimated $25 billion of damage, according to the National Hurricane Center. However, Standard & Poor’s estimated that if Andrew had made landfall in Miami, the damage could have been between $60 billion and $80 billion.

The insurance industry had to wake up to a new and dangerous reality: insured property loss was increasing at an unmanageable rate. A spike in property values coupled with a population shift to heavily insured areas was making insurance exposure a palpable problem. Insured property losses in the US between 1989 and 1995 were $75 billion, 50% more than in the 40 years preceding that time period, says an S&P report.

“One of the issues here is that [the reinsurance companies] have exposures that put them at low-frequency, high-severity risk,” says James Doona, a director in the insurance capital markets division of Standard & Poor’s. “Sometimes that coverage is difficult to purchase.”

By issuing catastrophe bonds, which tend to be rated in the double-B range, the reinsurance market is passing the risk on to the capital markets, which are more equipped to handle a disaster of an enormous magnitude. As market professionals point out, these structures are intended to provide security for only the most severe catastrophes, the once-in-a-lifetime event.

“The bonds are normally issued to protect from a catastrophe of extreme losses,” says Rodrigo Araya, senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service. “In the last seven years, there’s been no such event that would trigger [a loss of principal]. It would take a repeat of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.”

In a typical cat bond structure, a reinsurance company will create a special-purpose vehicle (SPV). That SPV will issue the actual bonds, which will back a reinsurance agreement with the original company. Assuming all goes well and there is no catastrophe, the investors who purchased the bonds will receive the principal back at the time of maturity, plus the interest, which can be upwards of 5% to 15%. However, a certain event – usually determined by a degree of property damage – could trigger payment of the collateral to the reinsurance company, meaning the investors lose their principal and interest.

Indemnity-based triggers, with payouts related to the size of issuers’ actual losses, however, have proven unpopular with investors because of the onerous task of understanding issuers’ portfolios of risk. Other issues incorporate index-linked triggers, which can be based on industry loss indices, or even external events such as a specific Richter scale or wind speed measurement. Many investors prefer index-linked triggers because they are measured by a third party and are very simple to understand – and thus difficult to dispute.

Pulling the trigger

One cat bond that has caused a degree of consternation during this hurricane season is Residential Re 2003, in which aggregate losses during the entire season can cause the bonds to trigger. However, there is still an exceedingly high bar to be met.

Residential Re 2003, a reinsurance subsidiary of United Services Auto Association (USAA), only takes into account the losses in around 20 covered states, with USAA retaining the first $150 million, and excluding allocated loss adjustment expenses (ALAE), auto losses, mobile home losses and boat losses, explains S&P’s Doona. Additionally, there is a 10% coinsurance retention applied before the trigger calculation, and ALAE and auto losses normally amount to about 15% of the loss estimate, so 25% is a conservative haircut.

In order to reach Residential Re’s trigger of $612 million, the loss estimate would have to gross up for the 10% coinsurance, the more than 15% exclusions and the initial retention, so the rough estimate of gross losses in the covered states might have to reach about $966 million to trigger attachment of the reinsurance, says Doona. The gross amount that experts speculate has been lost to date is $620 million.

Despite the inherent danger of cat bonds, these securities continue to increase in popularity. In 2003, $1.73 billion in catastrophe bonds were issued, according to reinsurance advisory firm Guy Carpenter & Company, a 42% increase year-over-year from 2002’s $1.22 billion of issuance. Although risk-takers stand to lose their entire investments, investors are drawn by the fact that these bonds are uncorrelated to anything else they have in their portfolios. And it can’t hurt that nobody has ever lost their principal in these instruments yet.

Betting on mortality Late last year, Swiss Re Capital Markets Corporation privately placed $400 million of principal at-risk variable-rate notes through its special-purpose vehicle, Vita Capital. Oddly enough, the notes were linked to catastrophic mortality. Vita Capital (ironically, vita means life in Latin) is structured such that the triggering event is determined by a increase in mortality rates in any of several countries, according to a Moody’s report. The countries are the US, the UK, France, Switzerland and Italy. In its essence, investors are betting on the fact that a catastrophic event will not happen during the maturity period of the bonds, which would cause a substantial rise in the mortality rates of the five countries named. |

Readers can also access free, the Credit Forum on credit index trading,which is particularly relevant to investors now that the tradable CDSindices Dow Jones iTraxx and CDX have established near-universal marketacceptance. Several bankers give their views on this new phenomenon.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Credit markets

Liquidnet sees electronic future for grey bond trading

TP Icap’s grey market bond trading unit has more than doubled transactions in the first quarter of 2024

Single-name CDS trading bounces back

Volumes are up as Covid-driven support fuels opportunity for traders and investors

Podcast: Richard Martin on improving credit migration models

Star quant proposes a new model for predicting changes in bond ratings

CME to pass on Ice CDS administration charges

Clearing house to hike CDS index trade fees from July after Ice’s determinations committee takeover

Buy side fuels boom in single-name CDS clearing

Ice single-name CDS volumes double year on year following switch to semi-annual rolls

Ice to clear single-name bank CDSs from April 10

US participants will be able to start clearing CDSs referencing Ice clearing members

iHeart CDS saga sparks debate over credit rules

Trigger decision highlights product's weaknesses, warns Milbank’s Williams

TLAC-driven CDS index change tipped for September

UK and Swiss bank Holdco CDSs likely inclusions in next iTraxx index roll, say strategists