Swaps data: breaking down CCPs’ $750 billion funding bill

Amir Khwaja of Clarus FT considers how initial margin, variation margin and default fund contributions can quickly add up

Initial margin, variation margin and default resources are three key weapons used by central counterparties (CCPs) to protect against risk. Under the voluntary Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the International Organization of Securities Commissions public quantitative disclosures, over 200 quantitative data fields covering margin, default resources, credit risk, collateral, liquidity risk and more are published each quarter.

The most recent available data is for the quarter ending September 30, 2017, and shows some interesting insights. For instance, across the three metrics, the total funding requirement for all CCPs could be as high as $750 billion. Variation margin calls could be as much as 2.5 times the average, while over half of initial margin is posted as government bonds.

Initial margin required

Initial margin required from participant members is a good measure of the size of risk managed by a CCP and, aggregating this information for a wide selection of major clearing houses, we get a grand total of $500 billion.

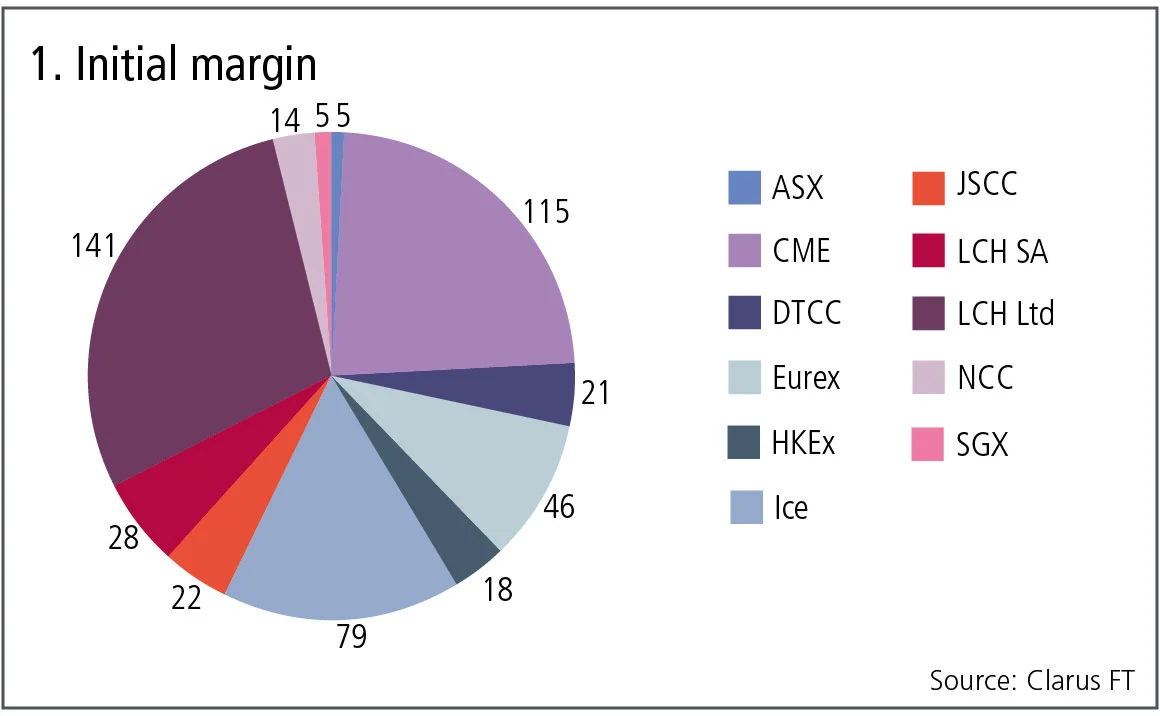

Figure 1 is the breakdown for a clearing house, with the constituent CCPs aggregated in billions of dollars.

Figure 1 shows:

- LCH Ltd with $141 billion of initial margin is the largest, of which SwapClear contributes $121 billion.

- CME is next with $115 billion.

- Ice has $79 billion, aggregating Ice Clear Credit, US futures and options, Ice Clear Europe Credit and its futures and options – no data is available for other Ice-owned CCPs.

- Eurex with $46 billion.

- LCH SA with $28 billion and the Japan Securities Clearing Corporation with $22 billion.

- The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation with $21 billion, of which the government securities division contributes $11.7 billion.

Initial margin type

A grand total of $500 billion of initial margin is required, which is a large sum indeed. Remember, this is the amount that members are required to post at the CCP, so it is real money and not a notional number.

Let’s look at data on how these clearing houses hold initial margin funds.

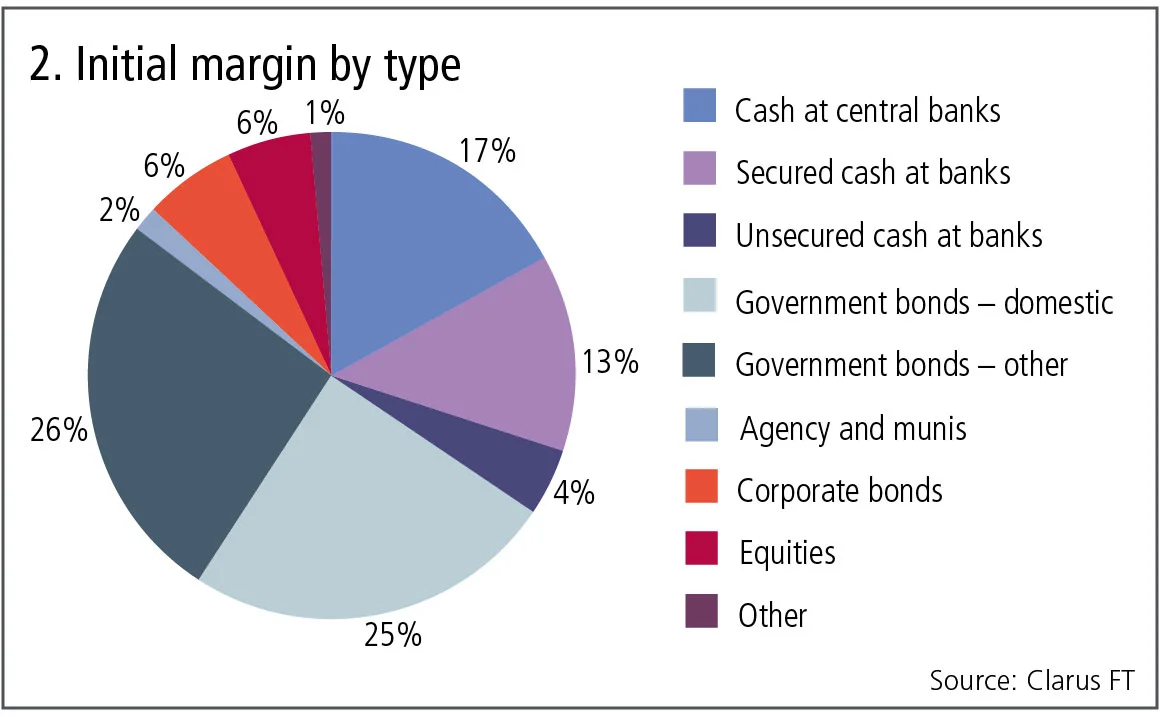

Figure 2 shows:

Government bonds are by far the largest at 51%, made up of almost equal amounts of domestic – meaning the sovereign of the CCP’s location – and other, meaning foreign country sovereigns.

- Cash at central banks is the next largest at 17%.

- Secured cash at commercial banks is 13% and includes reverse repo transactions.

- Corporate bonds and equities are 6% each.

- Unsecured cash at commercial banks is 4%.

Clearing houses will impose larger haircuts on riskier securities, and these figures use pre-haircut amounts, there is additional data on the post-haircut amounts of these types, but this does not materially alter the above percentages.

Total variation margin

CCPs also collect and post daily variation margin to participant members to reflect the daily profit and loss of their positions. Let’s look at the size of these flows.

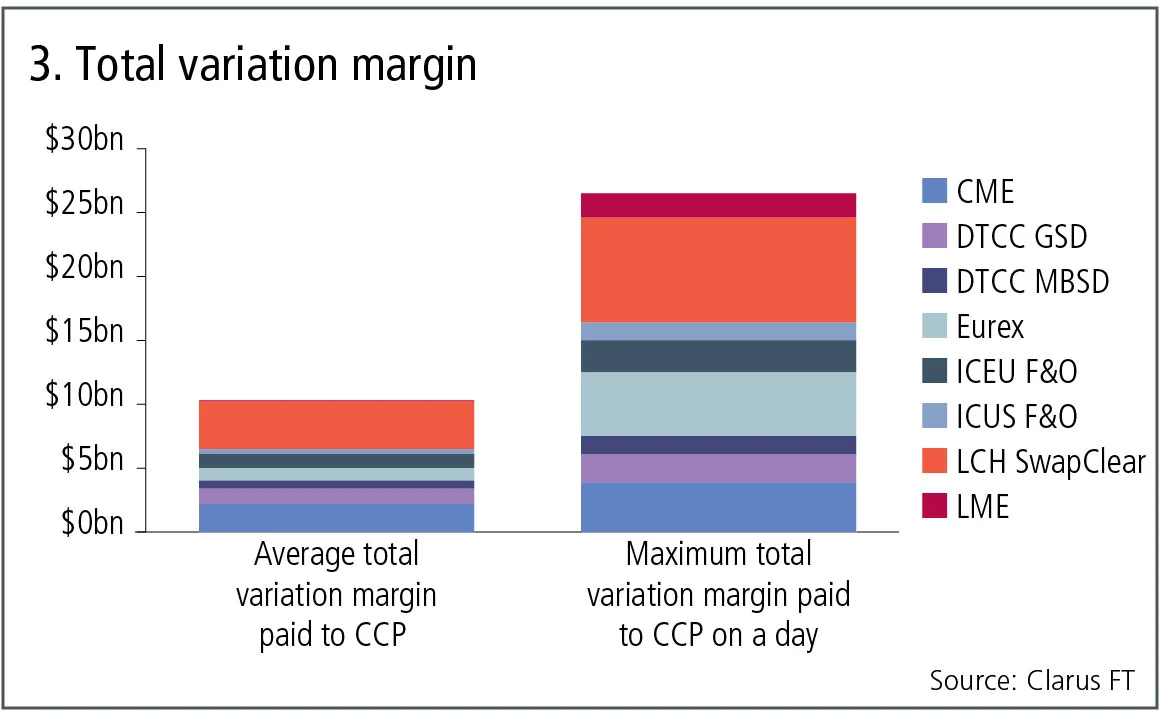

Figure 3 shows:

- Average total variation margin paid to a CCP and the maximum total variation margin paid to a CCP on a day in the quarter ending September 30, 2017, for selected CCPs with large variation flows.

- The grand total for these eight CCPs is $10 billion, meaning on average this amount is being collected by CCPs from members and the same amount posted to other members.

- LCH SwapClear at $3.7 billion and CME at $2.2 billion are the largest two contributors.

- The total of maximum total variation in a day in the quarter is $26 billion, so two and a half times as large as the average.

- LCH SwapClear at $8.2 billion and Eurex at $5 billion are the largest two contributors.

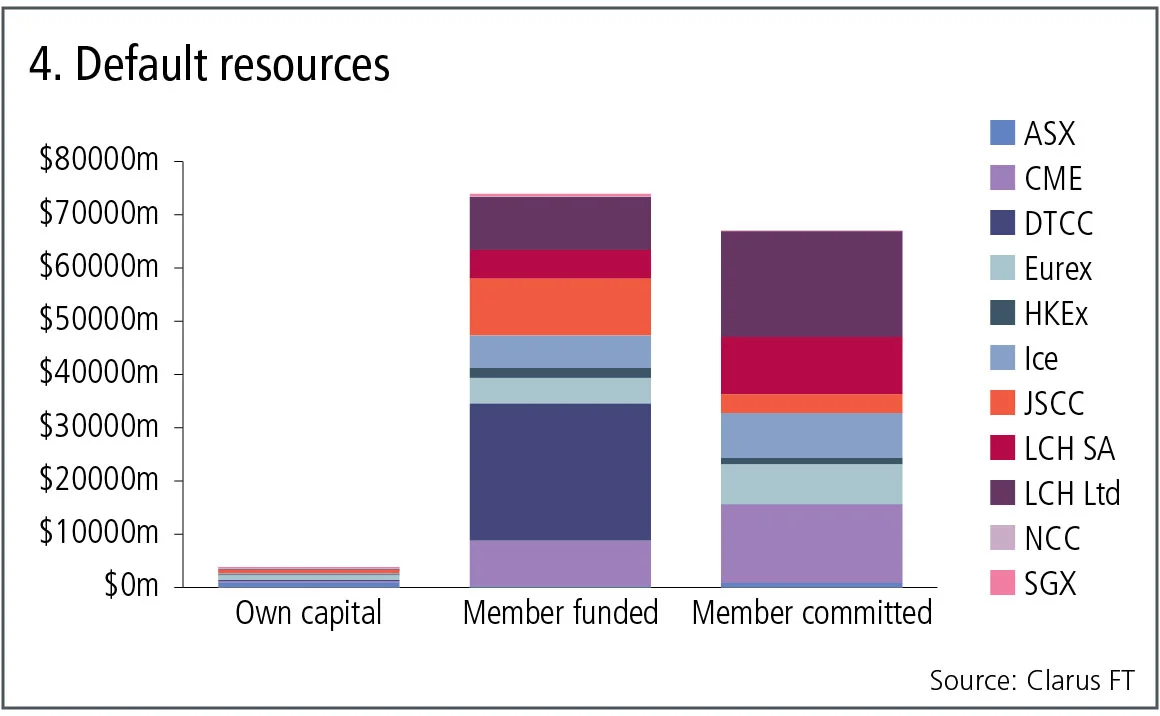

Default resources

Besides initial margin and variation margin, the other important measure of a CCP’s significance is the default fund or guarantee fund. These are the resources that will be called into action should a defaulting member’s variation margin, initial margin and pre-funded default fund contribution not be sufficient to close out their positions. As such it provides the backstop that gives a high level of confidence to the safety and risk management provided by a CCP.

Let’s look at these default resources for the same clearing houses that we aggregated initial margin by their constituent CCPs.

Figure 4 shows:

- Three columns: the clearing houses’ own capital; member-funded contributions, so already held by the CCP; and member-committed contributions that would be available in the event of a default, should they be needed.

- Clearing houses’ own capital of $3.8 billion is the smallest of these figures and there has been much comment over recent years on “skin in the game” and whether CCPs should be required to have more of their own capital. However, there has been no movement by the regulators who authorise, monitor and stress test CCP models and resources, which by implication means they are satisfied by the amount of this capital.

- Member-funded contributions are very significant at $74 billion – this is cash or securities provided by members to CCPs.

- DTCC has the largest amount of member-funded contributions at $26 billion, followed by LCH Ltd at $10 billion.

- Member-committed contributions are next at $67 billion.

- LCH Ltd has the largest share at $20 billion, followed by CME at $15 billion.

Initial margin, variation margin, default resources

In the preceding section we have looked at the three key numbers, initial margin, variation margin and default resources and shown that for selected major CCPs, these amount to:

- $500 billion of initial margin.

- $10–26 billion of variation margin.

- $78–145 billion of default resources.

- A grand total of $670 billion.

A big number, but one that is likely to be higher if more CCPs are included, for example B3 in Brazil or Shanghai Clearing in China, perhaps by $30 billion to $80 billion.

Irrespective of whether the number is $670 billion or $750 billion, the size of these numbers shows the systemic importance of CCPs as a major part of financial market infrastructure.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Comment

Markets never forget: the lasting impression of square-root impact

Jean-Philippe Bouchaud argues trade flows have a large and long-term effect on asset prices

Podcast: Pietro Rossi on credit ratings and volatility models

Stochastic approaches and calibration speed improve established models in credit and equity

Op risk data: Kaiser will helm half-billion-dollar payout for faking illness

Also: Loan collusion clobbers South Korean banks; AML fails at Saxo Bank and Santander. Data by ORX News

Beyond the hype, tokenisation can fix the pipework

Blockchain tech offers slicker and cheaper ops for illiquid assets, explains digital expert

Rethinking model validation for GenAI governance

A US model risk leader outlines how banks can recalibrate existing supervisory standards

Malkiel’s monkeys: a better benchmark for manager skill

A well-known experiment points to an alternative way to assess stock-picker performance, say iM Global Partner’s Luc Dumontier and Joan Serfaty

The state of IMA: great expectations meet reality

Latest trading book rules overhaul internal models approach, but most banks are opting out. Two risk experts explore why

How geopolitical risk turned into a systemic stress test

Conflict over resources is reshaping markets in a way that goes beyond occasional risk premia