Nine years later, RMBS woes still haunt banks

Megan van Ooyen from SAS rounds up the top five operational risk losses for April 2016

Megan van Ooyen is a senior associate business operations specialist in the OpRisk Global Data group at SAS in North Carolina

In the early and mid-2000s, the US housing market was booming. Mortgage lenders scrambled to respond to eager homebuyers and handed out mortgage loans like candy. If you had a pulse and a dollar in 2005, banks stamped 'approved' on your loan application before you could blink.

Unfortunately, a dollar doesn't go very far when the monthly mortgage payment is due, and homeowners found themselves unable to afford their overpriced homes. By 2007, foreclosure rates were skyrocketing and subprime lenders were declaring bankruptcy. And, as thousands of investors soon discovered, subprime mortgages were about to gut their portfolios.

For years, banks had securitised loans from subprime lenders, repackaged them, and sold them to investors as residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBSs). Sellers touted the securities as safe, conservative investments, but the values of RMBSs were highly dependent on the strength of the US housing market. When that market collapsed, it dragged RMBSs down with it, and investors lost billions.

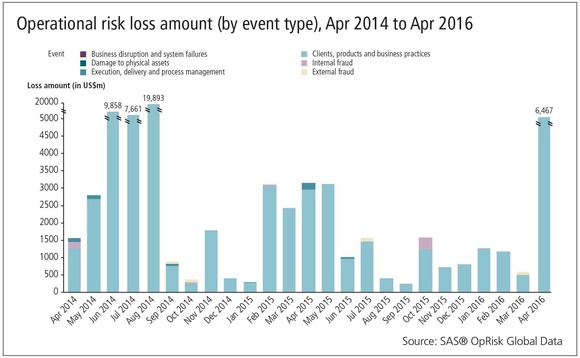

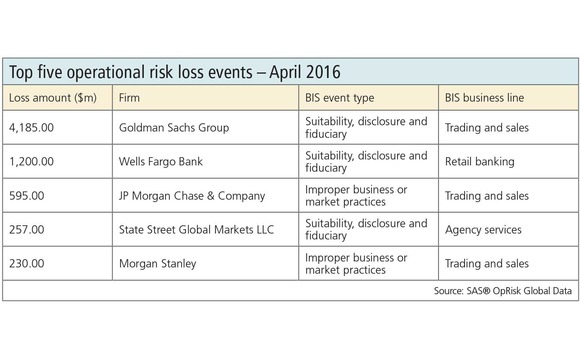

Even though the RMBS bubble burst almost a decade ago, the financial services industry continues to suffer the consequences. In the nine years since the housing crisis began, there have been 67 loss events in which financial institutions lost at least $1 billion. About a third of those multi-billion-dollar incidents involved the underwriting, securitisation and sale of RMBSs. Two of the top five loss events in April 2016 involved either the sale of RMBSs or the lax underwriting standards that made the products so risky.

First, Goldman Sachs became the fifth bank to settle with the US Department of Justice and several other government entities over the sale of questionable RMBSs. From 2005 to 2007, the bank admitted it securitised loans that didn't meet accepted underwriting standards. It even ignored its own internal controls when its due diligence process flagged defective loans. The majority of the $4.19 billion loss will go towards civil penalties and consumer relief. The remaining $875 million will settle pending lawsuits filed by the US National Credit Union Administration, Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago, Federal Home Loan Bank of Seattle, and the states of California, Illinois and New York.

Second, Wells Fargo came under fire for poor underwriting before the crisis. In 1934, the US government created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to support the housing market during the Great Depression. The FHA insures lenders against the default of borrowers, giving banks the confidence to issue mortgage loans to higher-risk customers. In order to streamline the process, the administration authorised lenders such as Wells Fargo to originate, underwrite, and endorse mortgages for FHA insurance.

But during the peak of the housing boom, the bank put its underwriters under enormous pressure to offer loans regardless of borrowers' qualifications. Consequently, more than half of the loans Wells Fargo endorsed for FHA insurance between May 2001 and October 2005 did not meet FHA quality standards.

To make matters worse, the bank identified more than 6,500 defective mortgage loans it had certified for FHA coverage and neglected to inform the administration. The loans inevitably defaulted, and the FHA reimbursed the bank, even though Wells Fargo should not have endorsed the loans in the first place. The bank vehemently denied shirking its responsibilities, yet offered a $1.2 billion olive branch to avoid a potentially more costly trial.

RMBSs are not the only credit instrument that caused op risk losses in April. In recent years, banks have been accused of manipulating the foreign exchange market and Libor, and now credit default swaps (CDSs) are also in the spotlight. In 2008 and early 2009, two US-based central counterparties – CMDX and Ice Clear Credit – were vying to clear CDS trades. CMDX was a joint venture between exchange CME Group and hedge fund Citadel, both based in Chicago, while Ice Clear Credit was backed by a consortium of major banks.

Twelve banks are accused of conspiring to block CMDX from the market, including by pressuring London-based data vendor Markit and the International Swaps and Derivatives Association to deny the new platform a licence to use their indexes. When CMDX eventually received its licence, the terms required the banks to be involved in every CDS transaction.

The banks' actions are alleged to have kept CDS prices artificially high, when increasing liquidity should have dropped prices. US investors filed lawsuits after newspaper reports and rumours of regulatory investigations revealed secret meetings among the banks and their affiliates. In April, the 12 banks reached a $1.87 billion settlement with investors that traded CDSs between 2008 and 2013. At the time, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley held the largest shares of the CDS market – and their settlements of $595 million and $230 million, respectively, were large enough to make the top-five list.

This first investor settlement may only be the beginning for those involved in the CDS market. Judging by similar anti-trust claims in the past, the banks likely face regulatory penalties in the US and elsewhere. In an era of splashy settlements, those penalties could be substantial.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Risk management

Japanese megabanks shun internal models as FRTB bites

Isda AGM: All in-scope banks opt for standardised approach to market risk; Nomura eyes IMA in 2025

Benchmark switch leaves hedging headache for Philippine banks

If interest rates are cut before new benchmark docs are ready, banks face possible NII squeeze

Op risk data: Tech glitch gives customers unlimited funds

Also: Payback for slow Paycheck Protection payouts; SEC hits out at AI washing. Data by ORX News

The American way: a stress-test substitute for Basel’s IRRBB?

Bankers divided over new CCAR scenario designed to bridge supervisory gap exposed by SVB failure

Industry warns CFTC against rushing to regulate AI for trading

Vote on workplan pulled amid calls to avoid duplicating rules from other regulatory agencies

Top 10 op risks: Change brings challenges as banks splash the cash

Higher interest margins and a trend toward insourcing drive major tech projects

Top 10 op risks: deepfakes drive rise in fraud fears

External fraud re-enters top 10 as artificial intelligence provides new tools for criminals

Should the ECB stress-test counterparty default risks?

The US Fed already does, but it is notable that EU banks were less exposed to Archegos

Most read

- Top 10 operational risks for 2024

- The American way: a stress-test substitute for Basel’s IRRBB?

- Filling gaps in market data with optimal transport