Filter furore: EU countries set to shield banks from bond volatility

It was the toughest part of Basel III for the US to swallow – a requirement that unrealised gains and losses on some bonds would hit bank capital calculations. In Europe, legislators provided an opt-out – and some countries have already chosen to use it, in breach of the Basel text. Lukas Becker reports

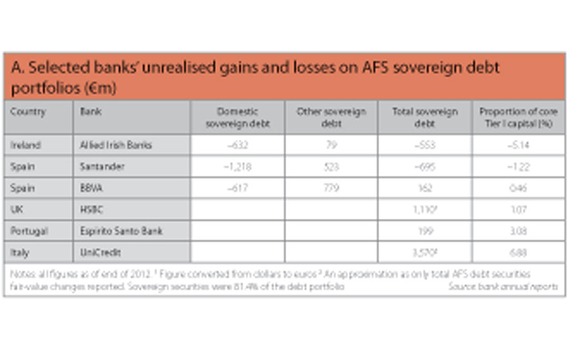

During 2012, Allied Irish Banks (AIB) saw €553 million wiped from the value of government bonds it was holding – a loss equivalent to just more than 5% of its Tier I capital. Happily for the bank, it did not have to take the hit because the bonds were held in its available-for-sale (AFS) portfolio, and Basel II filters AFS volatility out of regulatory capital numbers. Even more happily, while this filter is removed in Basel III, the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) plans to ignore that for the next few years – a discretion granted to national supervisors in June by European Union (EU) legislators – which would insulate the country’s banks from losses that could be unleashed as interest rates rise.

Germany’s Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (Bafin) and supervisors in some peripheral eurozone countries are expected to follow the CBI – a big win for their banks, but a further blow to relations between European authorities and those in the US, which chose to stick to the letter of Basel III and remove the filter for the biggest US banks when they published their own rules in July.

“The reason they did that is that they didn’t want to be accused of creating big exemptions that would give a green light to the Europeans to do the same. And now the Europeans are doing it anyway,” says a former US regulator, who was involved in Basel III discussions.

Tears are unlikely to be shed in the Bundestag, where the German parliament’s influential finance committee is championing the exemption. In a report published in May, the committee urged Bafin to use the discretion contained in the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), which is one half of Europe’s Basel III rules. Under the terms of the CRR, the filter could remain in place until an overhaul of International Accounting Standard (IAS) 39 has been completed, which could see AFS replaced as an accounting category.

“By exercising this discretion, regulators could avoid significant fluctuations of prudential capital for the institutions affected. The coalition parties would assume that Bafin will exercise this discretion granted to them by the CRR, taking into account bank regulatory principles,” the report says.

The reason they did that is that they didn't want to be accused of creating big exemptions that would give a green light to the Europeans to do the same

Ralph Brinkhaus, a member of the German parliament who sits on the committee, reiterates that view. “The finance committee’s report states that it would very much welcome a decision by the German supervisory authority, Bafin, to use this option in order to maintain the status quo until IAS 39 has been replaced by subsequent regulation and in order to avoid fluctuations of regulatory capital in affected banks,” he says in an emailed statement.

But there is no unity on the subject even within Europe. Sweden, for example, has already decided to remove the filter. “It has been agreed in Basel III that the prudential filter has to be taken away, and we think there is no need to subject government exposures to any particular treatment. So we wanted to keep the regulatory framework as conservative as Basel requires,” says Uldis Cerps, executive director for banks at Finansinspektionen, Sweden’s prudential regulator.

The story of what eventually entered into the official journal text of CRR as article 467(2) began in Italy in March 2012, when four Italian members of the European Parliament (MEPs) put forward amendments to the parliament’s version of CRR.

MEPs Alfredo Pallone and Herbert Dorfmann wanted to amend article 30 of the draft text – article 35 in the final journal text – which required the removal of all prudential filters to exempt “unrealised gains or losses on asset items constituting claims on Zone A central governments measured at fair value”. Zone A countries are the 35 full members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Two more Italian MEPs – Leonardo Domenici and Gianni Pittella – wanted to exempt “unrealised gains or losses on EU sovereign debt that are valued at fair value and held in the available-for-sale category”.

Italy had spent the second half of the previous year in the crosshairs of the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, with 10-year domestic government bond yields hitting 7.1% at the end of 2011. This affected Italian banks, too. In its 2011 annual report, UniCredit reported a €1.96 billion unrealised loss on its AFS securities, 70% of which consisted of government bonds.

A spokesperson for Dorfmann says the CRR amendment was made with this volatility in mind. “The intention was to exclude unrealised gains and losses of sovereign bonds from bank capital. Phases of high volatility in the sovereign bond market might lead to unjustified volatility of own-capital numbers and can distort regulatory ratios,” he says.

It’s not hard to see why politicians – particularly Italian ones – would be worried, but the argument is not necessarily self-serving. Banks tend to use AFS to park their liquidity buffers, specifically because it allows them to hold a big book of assets – as a hedge for deposits and other liabilities, for example – without having to worry about the volatility. The accounting quid pro quo is that banks should not buy and sell assets in an AFS portfolio frequently. As such, advocates of the filter argue it is inappropriate for volatility in these assets to show up in capital.

That proved to be a winning argument among Dorfmann and Pallone’s colleagues. The European Parliament’s Economic and Financial Affairs Committee (Econ) adopted their amendment, adding that the European Banking Authority should draft standards specifying how the rules will work until International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9 – the replacement for IAS 39 – was introduced in Europe.

The amendment quickly became a bone of contention in three-way talks between the parliament, European Commission (EC) and Council of the European Union. A January 7, 2012 version of the so-called trialogue text for the CRR, obtained by Risk, sees the EC describing the amendment as “imprudent”. The council, headed by Ireland at the time, had not proposed a similar amendment, suggesting the odds were stacked against the parliament.

A source close to the Econ committee says the EC’s primary objection was to the open-ended nature of the amendment, so a compromise was hammered out in which the adoption of IFRS 9 in Europe – scheduled for 2015 – would force member states to remove the filter, if they had not already done so.

As a result, the amendment moved out of what would become article 35 and was added to article 467, which details how unrealised gains and losses on non-government securities will be phased in between 2014 and 2017 – starting with recognition of at least 20% of losses in 2014 and increasing annually thereafter. At the same time, the decision about whether to retain the filter was placed in the hands of national regulators, and the text was clarified to state that the exemption applied to “exposures to central governments classified in the available for sale category” of IAS 39.

Tanya Foxe, financial services attaché at the permanent representation of Ireland to the EU in Brussels, who worked on the CRR for the council during the Irish presidency, declines to disclose the council’s position on the issue at the time, but says it was not a controversial topic and all sides were happy with the final wording.

The EC, meanwhile, plays down the significance of the opt-out. Mario Nava, director of the financial institutions directorate at the commission, says the time limit, and the fact that unrealised gains and losses are set to be introduced gradually between 2014 and 2017, negates its impact. “This is not a deviation, but an option, available only temporarily and linked to IFRS 9 endorsement. This option is likely to have basically no impact given the phasing of Basel III and the envisaged endorsement of IFRS 9 by 2015,” says Nava.

That changes if the IFRS 9 timetable slips, of course, and a senior accounting source at one UK bank says he is not expecting it to come into force until 2017. If that proves to be the case, banks benefiting from the exemption will have enjoyed at least three years of immunity to sovereign bond volatility – during a period when interest rates are expected to rise – while their competitors will be recognising a minimum of 80% of the price moves in AFS assets.

In some cases, it could be worse. The UK’s consultation paper on CRR implementation – published in August – proposes no phasing-in of losses, and no carve-out for sovereign bonds, so the full volatility of those portfolios looks set to hit capital from January 2014. It could mean Barclays, for example, finds itself grappling with big AFS swings for the next three years, while Deutsche Bank is shielded from the impact.

Fear of that impact dominated the comment period for the US version of Basel III, first published in June 2012. A survey of 14 large banks conducted by industry group The Clearing House concluded a 3% rise in rates would lead to a collective $44.6 billion fall in the value of banks’ AFS portfolios. In total, regulators received more than 1,200 comment letters, with a large number citing concerns about the removal of the filter (Risk March 2013, pages 32–36).

The authorities were under pressure behind the scenes as well, says the former US regulator. The US position initially was that unrealised AFS losses should continue to be excluded from capital numbers, he claims. Foreign supervisors dug their heels in and insisted the US should stick to the letter of Basel III.

“We were overruled by our foreign bank regulatory colleagues, who said this wouldn’t be a big deal. It turned out to be a very big deal,” says the former US regulator.

In the end, the US rule removed the filter only for the country’s largest banks – those with more than $250 billion in total assets – but that may not be the end of the story. A senior regulatory source at one large US bank says the Federal Reserve Board has spoken to the Basel Committee about revisiting the policy and potentially reinstating the filter for high-quality securities such as US Treasury and agency bonds.

The former US regulator says widespread use of the European opt-out could create a backlash in the US – and in other countries that have followed the text faithfully – potentially forcing the Basel Committee’s hand. If the committee doesn’t budge, he says it’s possible the US agencies could provide an exemption of their own for selected securities.

“If Germany is joined by a couple of other countries, I’m sure the big US banks will be pushing the regulators, saying: ‘You never believed in this, and the reason for doing it – namely, that if you don’t do it the others will create exceptions – is no longer valid’,” he adds. The Federal Reserve declined to comment.

So, the question is: which European regulators will allow their banks to put the filter back in for government exposures?

The CBI was first to announce its intentions, stating in its September 2013 consultation paper on the CRR that it would allow its banks to continue applying the AFS filter for unrealised gains and losses on government securities.

Then there is Germany. Unsurprisingly, the country’s federal banking association – the Bundesverband deutscher Banken (BdB) – agrees with the Bundestag finance committee that Bafin should keep the filter in place for government bonds. The BdB is not content with a temporary exemption, though. Anticipating a post-IFRS 9 landscape in which the AFS category is replaced with something similar – current proposals dub it fair value through other comprehensive income (FVOCI) – the association wants to see the filter reinstated for good.

“We need the filter until IFRS 9, but we need it after IFRS 9 as well because of the change of the concept of IFRS. The great fluctuations in capital expected to stem from changes in interest rates will be the same with IFRS 9, as the assumption is that a lot of securities – not just government bonds – will be put in the FVOCI category,” says Dirk Jäger, a banking supervision and accounting specialist at the BdB.

In the UK, the Prudential Regulation Authority’s (PRA) August consultation on CRR does not mention article 467(2). In fact, it heads in the opposite direction, proposing that UK banks should recognise 100% of their unrealised losses in capital from January 1, 2014, which implies a reprieve for government bonds is unlikely. A spokesman for the PRA does not exclude use of the opt-out, saying the regulator will consider reactions to the consultation paper and set out its response in a December policy statement.

The reactions to-date have been fairly glum. In its comment letter, the British Bankers’ Association (BBA) says it is surprised and disappointed the filter is not being reinstated for government bonds. “We were under the impression that the PRA would utilise these discretions. This will result in our members having to reconsider their capital plans, which is not a light undertaking, and is far from ideal,” said the BBA.

To the surprise of many, Greece decided not to allow its banks to replace the filter. Amalia Gida, a capital and accounting specialist with the Bank of Greece, says all filters were removed on March 31, with no exception made for government exposures. She offers no further explanation, but the 2012 restructuring of Greek debt has left domestic banks with greatly reduced exposures to their own country’s sovereign bonds when compared with banks in other periphery countries.

Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain are all currently undecided about whether to use the opt-out. Market participants, though, expect Italy, Portugal and Spain to do so, given their banks’ large holdings of potentially volatile domestic government bonds (see table A). Spain’s Santander, for example, held €29.3 billion of Spanish government debt in the AFS category at the end of 2012, equal to just over half net Tier I capital of €56.8 billion. The bank saw a €1.22 billion unrealised loss on this position for the year.

A senior executive at one of the big Spanish banks says he expects Banco de España to use the opt-out in order to underpin forthcoming Spanish auctions. “I know for a fact there is pressure on banks to take big chunks of home-country sovereign debt on their books. I do not know the Spanish regulator will allow it for sure, but I would not be surprised,” says the source.

Other countries may well come to the same conclusion, says Kevin Petrasic, partner in the global banking and payment systems practice at law firm Paul Hastings in Washington, DC. Without the filter in place, banks are likely to shorten the duration of their government exposures to ensure their portfolios are less correlated to interest rates when they start to normalise (see box).

“I think the countries are doing this more for them than for the banks. As far as the countries are concerned, shorter-term securities issued by the various governments will probably be fine but anything of a longer duration is going to have an impact – it’s going to be hard for institutions to carry them. They will inevitably move to shorter-term bonds, and that will kick up the borrowing costs for any longer-term debt,” says Petrasic.

Azad Ali, a counsel in the global financial institutions advisory and financial regulatory group at law firm Shearman & Sterling in London, says it’s a simple case of self-preservation. “Because of the parlous state of their state obligations, the peripheral countries are not out of the woods yet. There’s no point making something worse by removing the prudential filter. It sounds to me like they’ll apply a prudential filter until they’re on firmer ground and then resort to the Basel III standard,” says Ali.

How to control the capital impact

While European supervisors work out whether to apply their opt-out, some banks are preparing for a world in which gains and losses on available-for-sale (AFS) securities – which appear in financial statements under other comprehensive income (OCI) – begin flowing through to Tier I capital.

“OCI is the relevant number from a regulatory capital perspective, and you need to take into account not only the existing volatility but also the future volatility, which means the risk measurement process needs to be a lot more sophisticated than before,” says Andreas Bohn, head of asset-liability management and funds transfer pricing at Barclays in London.

The extent of the volatility depends on the mix of securities – some are more sensitive to interest rate moves than others – and on how they are being used. Generally, assets held in AFS will be there to act as a liquidity buffer and to provide big, structural hedges. As an example, a bank may use fixed-rate government bonds to hedge the interest rate risk on fixed-rate liabilities. If rates rise, the liabilities would gain in value, while the bonds would suffer – but while the latter effects would flow through to capital in the new regime, the liabilities are likely to be held at amortised cost, meaning no offset to the bond volatility.

One way of side-stepping this would be to use interest rate swaps rather than bonds. The bank could hedge a fixed-rate liability with an interest rate swap in which it is the fixed-rate receiver. If it is allowed to designate this as a fair-value hedge, changes in the two positions would offset each other. Ineffectiveness would be reported in the profit-and-loss account – affecting capital, but to a lesser extent than a cash position.

Another way of mitigating AFS volatility is for the bank to shorten the maturity of the debt it holds, reducing its sensitivity to – and correlation with – interest rate movements. Barclays’ Bohn says he would not want to hold durations of longer than two years, with five years and beyond replaced with interest rate swaps and put into hedge accounting.

But Rik Janssen, group treasurer at KBC in Brussels, notes that moving to shorter durations also reduces the yield a bank would receive – so any changes need to make sense within the broader context of the bank’s asset-liability management strategy.

For AFS debt securities that face credit risk as well as interest rate risk – for example, volatile eurozone periphery bonds – banks say they will either cut their holdings, or move them into the held-to-maturity accounting category. While this keeps unrealised gains and losses out of capital, it also places restrictions on a bank’s ability to sell the securities – a headache that could be lifted with the introduction of International Financial Reporting Standard 9, which replaces held-to-maturity with a new amortised cost category, which is likely to have fewer restrictions.

But the bottom line for many European banks is that they cannot decide how to manage their sovereign bond positions until they know whether they will continue to benefit from the AFS filter.

“Some of the actions we are considering would be meaningful in one state of the world but not in the other state. If sovereigns are taken out, then it doesn’t make any sense to put them in held-to-maturity as it reduces our flexibility but makes no difference regarding the volatility of the capital ratio. It has a huge impact on the way we manage these things,” says Janssen.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Risk management

Revealed: the three EU banks applying for IMA approval

BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and Intesa Sanpaolo ask ECB to use internal models for FRTB

FICC takes flak over Treasury clearing proposal

Latest plans would still allow members to bundle clearing and execution – and would fail to boost clearing capacity, critics say

Buy side would welcome more guidance on managing margin calls

FSB report calls for regulators to review existing standards for non-bank liquidity management

Japanese megabanks shun internal models as FRTB bites

Isda AGM: All in-scope banks opt for standardised approach to market risk; Nomura eyes IMA in 2025

Benchmark switch leaves hedging headache for Philippine banks

If interest rates are cut before new benchmark docs are ready, banks face possible NII squeeze

Op risk data: Tech glitch gives customers unlimited funds

Also: Payback for slow Paycheck Protection payouts; SEC hits out at AI washing. Data by ORX News

The American way: a stress-test substitute for Basel’s IRRBB?

Bankers divided over new CCAR scenario designed to bridge supervisory gap exposed by SVB failure

Industry warns CFTC against rushing to regulate AI for trading

Vote on workplan pulled amid calls to avoid duplicating rules from other regulatory agencies