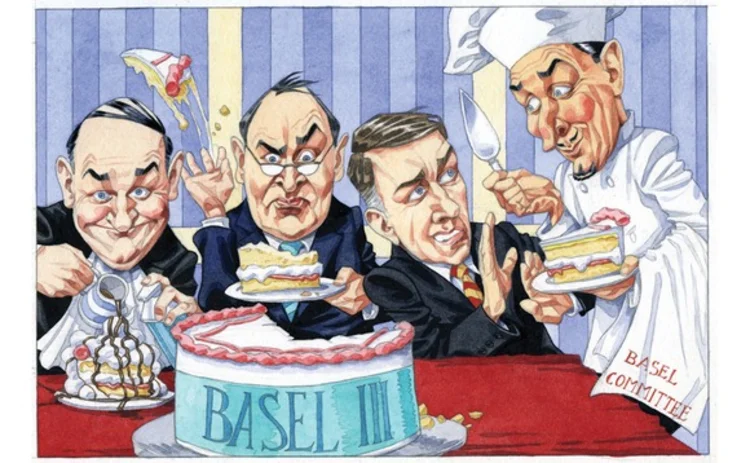

Different preferences create divided implementation of Basel III

Regulators are pinning their hopes on peer pressure to ensure consistent implementation of Basel III, but some of the new standards are still to be finalised, and the whole project could be blown off course by poor economic growth. By Michael Watt

The publication of Basel III in December 2010 may have marked the end of an intense one-year period of consultations and rule-writing by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, but it was just the start of a much longer process of implementation. For individual regulators, it meant working to transpose the regulation into national law – a process that is under way in Europe, for instance, through the drafting of the fourth Capital Requirements Directive.

The publication of Basel III in December 2010 may have marked the end of an intense one-year period of consultations and rule-writing by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, but it was just the start of a much longer process of implementation. For individual regulators, it meant working to transpose the regulation into national law – a process that is under way in Europe, for instance, through the drafting of the fourth Capital Requirements Directive.

The problem – at least as far as global banks are concerned – is that a number of differences are emerging across individual jurisdictions. In certain cases, national regulators are erring on the side of caution and adding to the minimum requirements; in others, they are playing around with the timings. A few countries, meanwhile, have made little progress at all in terms of implementation.

This is bad news for internationally active banks that may need to meet multiple local requirements – something the Basel Committee has recognised. In October, it published its first-ever progress report on Basel III implementation, the start of an ongoing programme of monitoring to ensure member countries are meeting the agreed timelines and complying with the letter of the rules. This was followed up by a second report in April. The question is whether this strategy of peer pressure will make any differences. The Basel Committee thinks it will.

“We want to ensure there is consistent application of the standards and a level playing field,” says Mitsutoshi Adachi, a director in the examination planning division at the Bank of Japan in Tokyo and a member of the Basel Committee’s standards implementation group (SIG), which is responsible for overseeing the global implementation process. “It is true we are not policemen – we do not have the power to enforce it. But the level of Basel III monitoring is unprecedented. The committee hasn’t done such rigorous peer reviews in the past. By doing serious peer reviews, any jurisdiction or region that is not compliant will come under peer pressure, and there will be regular publication of a progress report on Basel III. Any jurisdiction that is non-compliant will be publicly exposed.”

Other market participants are not so sure this will work. They claim the sluggish global economy is dampening the enthusiasm of some politicians to force their own banks to implement the framework. Any further evidence of a slowdown could blow the project off course in some jurisdictions, they argue.

It is absolutely vital for RWA calculations to be as transparent as possible, and for there to be proper oversight of the process so investors can make informed decisions

“There are already concerns at a very high political level that the reforms are placing too great a strain on the banking system. A fresh recession or an escalation of the eurozone crisis could throw the project off completely, and there is little the peer pressure approach could do to prevent this. Even a modest downturn could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” says one Scandinavian regulator.

Others make a similar point. “The economic recovery isn’t assured. You can make a strong case for saying that current and prospective regulatory reforms are playing a role in delaying the recovery. Requiring banks to raise more capital and more long-term funding in the current difficult circumstances is probably contributing to the de-leveraging, and that is hurting several of the mature economies. There is a recognition of the need to grasp the nettle when momentum for reform is high. But regulators need to recognise that elements of the reform programme may be placing such a strain on the banking system that it is actually contributing to economic weakness. It’s hard for banks to provide the credit needed to sustain a recovery under these circumstances,” says Paul Wright, a senior director at the Institute of International Finance (IIF) and a former regulator at the UK Financial Services Authority.

Even without the economy weighing on the process, a number of regulators have decided to go their own way. In some cases, authorities are keen to apply the minimum capital requirements set out in Basel III earlier than the officially mandated deadline. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, for instance, proposed in September 2011 that banks should meet the revised minimum capital ratios in full from January 1, 2013, and be fully compliant with the capital conservation buffer from January 1, 2016 – a timeline it reaffirmed in draft prudential standards released on March 30. In contrast, Basel III requires banks to meet a higher minimum common equity Tier I to risk-weighted asset (RWA) ratio of 4.5% by January 2015, and meet the 2.5% capital conservation buffer in full from January 2019.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Basel Committee

FRTB implementation: key insights and learnings

Duncan Cryle and Jeff Aziz of SS&C Algorithmics discuss strategic questions and key decisions facing banks as they approach FRTB implementation

Basel concession strengthens US opposition to NSFR

Lobbyists say change to gross derivatives liabilities measure shows the whole ratio is flawed

Basel’s Tsuiki: review of bank rules no free-for-all

Evaluation of new framework by Basel Committee will not be excuse for tweaking pre-agreed rules

Pulling it all together: Challenges and opportunities for banks preparing for FRTB regulation

Content provided by IBM

EU lawmakers consider extending FRTB deadline

European Commission policy expert says current deadline is too ambitious

Custodians could face higher Basel G-Sib surcharges

Data shows removal of cap on substitutability in revised methodology would hit four banks

MEP: Basel too slow to deal with clearing capital clash

Isda AGM: Swinburne criticises Basel’s lethargy on clash between leverage and clearing rules

Fears of fragmentation over Basel shadow banking rules

Step-in risk guidelines could be taken more seriously in the EU than in the US