In a differentleague

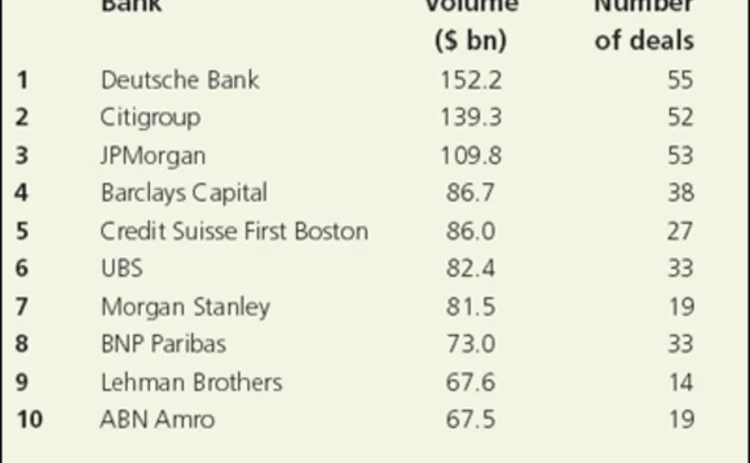

The issue of bookrunner league tables is one of the corporate bond market’s perennialbugbears. In an effort to unearth a metholodogy that accurately reflects more than justvolume of deals, Credit has come up with a few variations on a theme

Last month Credit asked whether a new issue league table could be produced that gave more insightful information than merely which bank has brought most bonds to market. While such information is interesting in an academic sense, Credit argued it is not really useful in any practical sense to any of the interested parties. Rather, the present league tables disrupt the market, banks waste money

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Rankings

TP ICAP: leveraging a unique vantage point

Market intelligence is key as energy traders focus on short-term trading amid uncertainty

GEN-I: a journey of ongoing growth

GEN-I has been expanding across Europe since 2005 and is preparing to expand its presence globally

Bridging the risk appetite gap

Axpo bridges time and risk appetite gaps between producers and consumers

Axpo outperforms in the Commodity Rankings 2024

Energy market participants give recognition to the Swiss utility as it brings competitive pricing and liquidity to embattled gas and power markets

Hitachi Energy supports clients with broad offering

Hitachi Energy’s wide portfolio spans support for planning, building and operating assets. Energy Risk speaks to the vendor about how this has contributed to its strong Software Rankings performance in 2024

Market disruptions cause energy firms to seek advanced analytics, modelling and risk management capabilities

Geopolitical unrest and global economic uncertainty have caused multiple disruptions to energy markets in recent years, creating havoc for traders and other companies sourcing, supplying and moving commodities around the world

ENGIE empowers clients globally to decarbonise and address the energy transition

In recent months, energy market participants have faced extreme volatility, soaring energy prices and supply disruptions following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, they have needed to identify and mitigate the longer-term risks of the…

Beacon’s unique open architecture underlies its strong performance

Recent turmoil in energy markets, coupled with the longer-term structural changes of the energy transition, has created a raft of new challenges for market participants