EM sell-off a buying opportunity, says Ada

Emerging market investors need to rethink their strategy, says Ada Investments chief Vinay Nair. He sees the recent sell-off as an opportunity for investors to build exposure to these markets

What a difference a decade makes. A savvy investor looking at emerging markets in 2003 noticed several tailwinds: trade integration of China; normalisation of balance sheets after the 1998 crisis; a new bullish cycle in commodity prices and falling real yields in the US.

The next five years saw the MSCI Emerging Markets Index post compound annual returns of 36%. By 2007 investors were rushing to emerging markets.

Then came the global financial crisis, rooted in the developed markets but inevitably affecting the emerging markets. Investors lost more than 25% in the past five years, even while interest and volumes remained high.

Recent market events are shining the spotlight on several risks in emerging markets.

Many investors are watching China with great interest. The emerging markets’ flag-bearer is shifting gears to build a consumption-based economy and rebalancing the economy is the number one priority in its current five-year plan.

This transition may take several years and has meaningful risks. For instance, the economy could experience an undue slowdown if consumption demand does not offset the reduction in investment.

There are several implications from this shift. The slowing of Chinese urbanisation and reduction in infrastructure investments might signal the end of the bullish cycle in commodity prices since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2000. If so the spillover effects will impact many commodity exporters negatively.

Separately, there is the risk that the normalisation of the US economy will increase yields in the US and reduce the attractiveness of emerging markets. A shrinking interest rate differential in 2004 and 2006 had similar effects.

The withdrawal of foreign capital from many of these economies is already revealing the poor condition of their balance sheets and putting pressure on their currencies. In some cases this weakening of the currency is increasing consumer prices and raising inflationary risks. Policy-makers in these regions are faced with the dilemma of raising rates to support the currency and tackle inflation or supporting the slowing growth.

Political risks have also come to the fore. The obvious flaws in the structure of some governments were masked by solid rates of economic growth. This sense of stability is increasingly tenuous as growth slows and politics becomes unpredictable and potentially violent.

It is no wonder then that investors are suddenly fearful of putting money into emerging markets. But reducing allocations to these markets makes little sense in the long term.

A diversified portfolio that aims to benefit from global growth will find it difficult to avoid emerging markets. The region is no longer what it was in the early 1990s when it contributed less than 20% of global growth. Today emerging markets contribute about half of global growth and avoiding them leaves a significant hole in a portfolio.

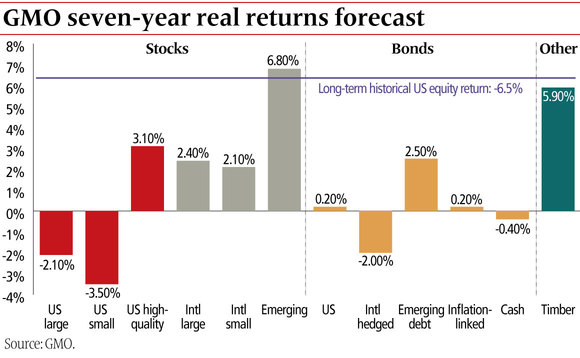

In addition most asset allocation models suggest a reasonable allocation to emerging markets due to the high long-term real return associated with emerging market stocks. The graph shows GMO’s seven-year forecast of real returns across some asset classes in July 2013. For an investor who even directionally believes in these forecasts, an allocation is worth some temporary discomfort in an otherwise low-yield environment.

Emerging markets are not only important for asset allocation but also potentially attractive in the long term. For an investor a healthy diet should include a portion of emerging markets. The widespread negative sentiment around emerging markets can provide a valuable entry point for longer-term investors.

We see three signs that suggest this may be a good time to start building an emerging markets portfolio.

In 2007 emerging markets were trading at a Shiller price to earnings (PE) ratio, which is based on average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years, of almost 37. Investors were pouring in notwithstanding the vast body of evidence that suggests that high Shiller PE ratios are associated with low returns over the next five years.

In comparison the US was trading at a Shiller PE ratio of around 26 in 2007 – a difference of around 11.

Today, emerging markets are trading at a Shiller PE ratio of around 12 while US stocks are at 24. The difference in valuations is at the other end of the spectrum. Yet again, notwithstanding the evidence that low Shiller PE ratios are associated with high future returns, the average investor is leaving emerging markets.

Of course, there is the concern that PE ratios in emerging markets do not reveal the complete picture since in many cases earnings never get to shareholders due to poor corporate governance.

This concern is not without merit and such valuation metrics should be viewed cautiously. So let us take a more direct and conservative measure that delivers cash to investors and also has significant predictability for future long-term returns: dividend yields.

The yield difference of emerging market stocks relative to US stocks is strongly correlated with future return differentials over the next five years. When emerging markets have larger dividend yields than the US, they tend to outperform in the next five years. The highest yield differential was in 1998.

Conversely, the yield differential was negative in 2007.

Today emerging market equities provide a dividend yield of around about 35% higher than the S&P 500’s yield of 2.1%. Based on today’s yield differential, one would expect a higher return in emerging markets over the next five years.

While other valuation metrics, such as price to book or price to earnings suggest a bigger gulf between US and the emerging markets, the current yield premium is not unusually high: it is roughly in the middle of the distribution of yield premium since 1990.

Looking a little deeper within emerging markets, an interesting feature of today’s markets is that higher-quality companies – those with low volatility, low leverage and high profitability – are trading at high multiples and do not appear cheap while lower-quality companies are trading at basement bargain prices. For example, high-quality companies are trading at a price to book multiple that is almost four times higher than the price to book of the lower-quality companies.

This quality premium is at a level not seen for at least a decade. Such a premium for high-quality companies is often a feature of markets that place an unwarranted premium on safety and are overly pessimistic. For example, in the US the peaks of the quality premium coincided with market sell-offs during the dotcom bubble and the 2008 crisis.

While it runs contrary to human instincts, all the evidence suggests that being a seller at these prices is not an attractive proposition.

Emerging markets are an important component of a portfolio and returns are likely to be attractive but there are still significant portfolio construction challenges. High volatility and gut-wrenching drawdowns often cause investors to liquidate their positions at the worst possible times and in ways that are damaging for maximising long-term wealth (high volatility magnifies behavioural biases). At best it hurts the process of compounding, the central tenet of which is to avoid dramatic drawdowns.

In all likelihood the macroeconomic environment suggests emerging market volatility and uncertainty will be a feature for the foreseeable period. In addition there are several region-specific features that further increase the volatility. For example, most of the emerging markets have the presence of a common and significant family owner across different companies and industries. This can pose a risk for investors. Earlier this year an unexpected tax audit of a Koc family company in Turkey led to declines in all enterprises in which the family had significant ownership.

Currency risks add to the challenge facing institutional investors, as exemplified by significant volatility in emerging market currencies over the past five years as well as a high cost of hedging these currencies. In addition to its direct perverse effect on risk, currency volatility also has indirect effects. In particular certain industries (such as export-oriented) do better with currency depreciation whereas others deteriorate.

There are some components of an emerging market strategy we believe can guide an investor entering these markets.

First we advocate using a basket of countries. Unlike between 2003 and 2007 when almost all emerging markets were lifted by a common tide, different regions now appear to have exposure to different sources of risks. In an environment with a greater likelihood of idiosyncratic political risks, a basket of countries provides investors the needed safety.

In constructing such a basket two features merit comment. First, countries with an attractive demographic (population, age, potential productivity increases) should be preferred. International investors seeking exposure to different engines of global growth will be best served by investing in a basket of domestic consumption-driven economies.

Second, the basket of countries should ideally diversify across commodity exposures. The commodity cycle and the potential risks due to the shift in China’s economy make a compelling case for such diversification. For example, a country such as Brazil (commodity exporter) provides a fruitful counterpoint to a country such as India (commodity importer).

Short-selling should be an important component of an emerging market strategy. Emerging equity markets are nascent and more inefficient than the equity markets in US or Europe. The inefficiencies present significant return generating opportunities for sophisticated investors. Some of these are opportunities require shorting.

The returns also tend to be higher on the short side in most regions, as these trades are less crowded.

An additional benefit of incorporating shorting is that it results in portfolios with lower volatility. The returns extracted from the inefficiencies are more stable and not subject to overall market movements. By combining the returns from inefficiencies with the returns from some market exposure and using a long-biased long/short approach may allow investors an exposure to this market with limited volatility and additional returns.

Investors should also be prepared to vary their long bias over time. This approach is also attractive because there are structural aspects of these markets that can guide the extent of the long bias. In most of these markets international capital flows are an important factor. These capital flows exhibit momentum.

Additionally, many of these markets have lower liquidity than in developed markets making prices sticky. Both these aspects together create greater predictability in market returns over time, making it possible, albeit with lower confidence than we would ideally like, to adjust market exposures over time.

Varying the long bias also has a bigger impact in emerging markets since extreme bearishness and bullishness occur more often in emerging than in developed markets. The once-in-a-generation seesaw markets investors witnessed in the US in 2008 and 2009 happen more frequently in many emerging markets.

The current environment is also helpful for this exercise. This is because the two big groups of investors – international and domestic – have significantly different costs of capital today. When prices rise due to international inflows, many domestic investors that have access to attractive fixed income choices start moving away from equity markets. This is because future returns now no longer justify holding stocks and they become net sellers.

This trend continues until there is a shock that increases the risk aversion of the international investor and causes them to liquidate their ‘risky’ emerging market positions. Such a risk-driven liquidation, such as being witnessed now, drives prices to levels that become attractive for the domestic investors.

Smart domestic investors build their positions and sell into the next international investor-driven rally. This game of passing hot potatoes between domestic investors and international investors has largely characterised emerging equity markets over the past five years. The gap between the costs of capital can reduce due to changes in monetary policies but they can also be bridged due to increased currency volatility.

Next, currency insurance can be extremely valuable in emerging markets. While emerging markets have come a long way from the 1980s and many currencies are now market based many risks still remain.

Considering the costs of hedging as well as the central thesis and timing of entering these markets, we advocate holding some of this currency risk while purchasing insurance against extreme moves such as those witnessed in a currency crisis or a run. One mechanism to hold insurance is through deep out-of-the-money put options on the local currency.

The cost of such an option is significantly lower than a complete hedge and also allows an investor to participate in some of the upside. Unless one is a macro investor with expertise in knowing when to buy or sell the currency, this is one way to achieve an intermediate solution between complete hedging and a naked exposure.

Finally, timing can be everything in emerging markets. For example, an emerging markets investor in 2007 had a different experience compared to 2003. We believe an investor today is likely to have a very different experience from the one in 2007.

Other interesting periods of entry have been 1998 (post-Asian crisis) and 2004. All this goes to show that building a portfolio in these markets needs patience as well as decisive action when markets suggest an entry point. There is of course a risk of making a mistake.

We believe any emerging markets portfolio should be built in stages over periods when the general sentiment is unclear or negative. Staging the investments is one of the most effective forms of risk mitigation in these markets.

While advocating a closer look into emerging markets and being excited about the future return prospects in the current environment, we acknowledge that the negative sentiment today could get worse. We believe the cost of capital in these markets is beginning to reflect the expected normalisation of rates in the developed world but there have been no signs of a normalisation of cashflows and growth in these markets.

Whether the catalyst for the normalisation of cashflows is spillover of earnings from the developed markets, or greater political will or some other event is unclear. However, that uncertainty is exactly what we believe is creating the current environment and a generational opportunity to allocate capital in these markets, much like the US equity markets in 2008-09.

Taking advantage of this opportunity will, however, need a deeper understanding of portfolio construction in the context of emerging markets.

Vinay Nair is managing partner and CEO of Ada Investments.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Strategy

CTAs beat hedge fund rivals in 2014

Investors hope that CTAs’ fortunes have changed for good

Multi-strategy hedge fund assets surpass $400 billion

Investors flock back to strategy after years of trickling inflows

Hedge funds cautious on Argentina

How might hedge funds take advantage of opportunities in Argentina?

Hedge funds face growing risk, technology and data challenges

Sponsored feature: Broadridge Financial Solutions

A promising future

Sponsored statement: NYSE Liffe

Government bond traders see difficult markets heading into 2014

Your word is my bond

Hedge funds increase Asia quant investing risk capital by 50%

An improved Japan economy is ramping up quant investor activity across Asia

CTA trend followers suffer in market dominated by intervention

Return to normality

Most read

- Top 10 operational risks for 2024

- Top 10 op risks: third parties stoke cyber risk

- Japanese megabanks shun internal models as FRTB bites