Strong banks, weak stocks: should regulation share the blame?

Analysts say regulatory risk plays a part in weak bank valuations and wobbly prices

Need to know

- Equity analysts say post-crisis regulation is making it harder to forecast bank earnings, which is translating into depressed valuations for the industry and more volatile share prices.

- This might help explain the savage sell-off banks endured in January and February, when even US banks – on the back of a successful 2015 – saw their shares fall 30% or more.

- "Regulatory uncertainty has robbed investors of any confidence in these stocks," says Simon Samuels, a banking consultant.

- Opinions among regulators vary – at the Deutsche Bundesbank, Andreas Dombret concedes "regulatory uncertainty may contribute" to bank stock volatility. A peer at another European supervisor sees the claim as an extension of the industry's lobbying.

- But policy-makers agree stock prices are an important prudential factor – indicating resilience - and that price falls can result in a wider, self-perpetuating collapse in confidence.

- There are other systemic concerns, says one banker: "There are long-term implications of equity market weakness. Is this an industry that can attract capital, or is this an industry that needs to shrink?"

By some measures, banks are stronger than they have been since the 1930s. At the same time, their stocks seem more fragile.

After racking up record profits in 2015, US banks were caught in an indiscriminate six-week sell-off at the start of this year, wiping roughly a third from the market values of Bank of America, Citi and Morgan Stanley, while also hammering their European rivals. Deutsche Bank's chief executive had to defend its solvency, and fears were raised of a new systemic crisis. It was a rout with no obvious cause and, to some observers, that makes it scarier.

"Nobody cares about the fundamentals. All they care about is the monster under the bed," says Richard Bove, equity research analyst at Rafferty Capital Markets in Florida.

That monster could be years of slow growth and low interest rates that hold down bank revenues, or a coming tsunami of credit and conduct losses that destroy capital - but a common bugbear, when speaking to banks, analysts, and investors, is the uncertainty created by still-accreting layers of post-crisis regulation.

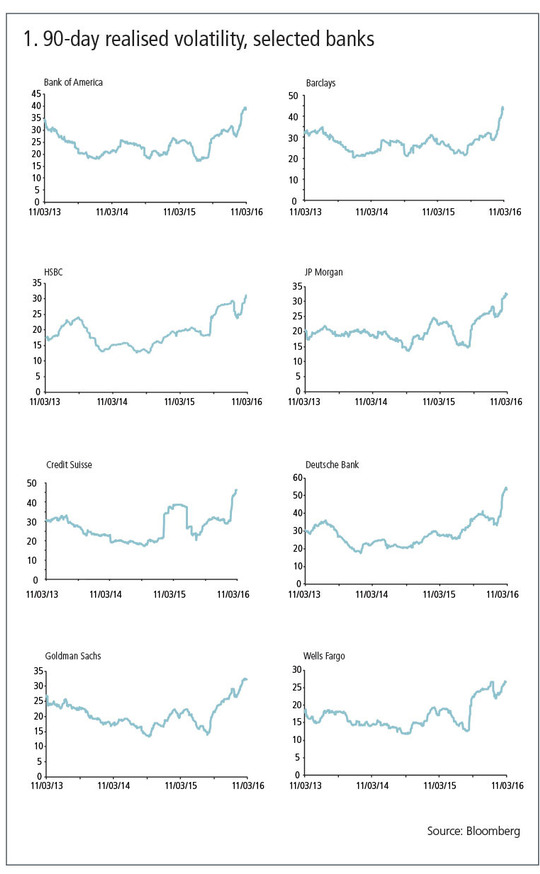

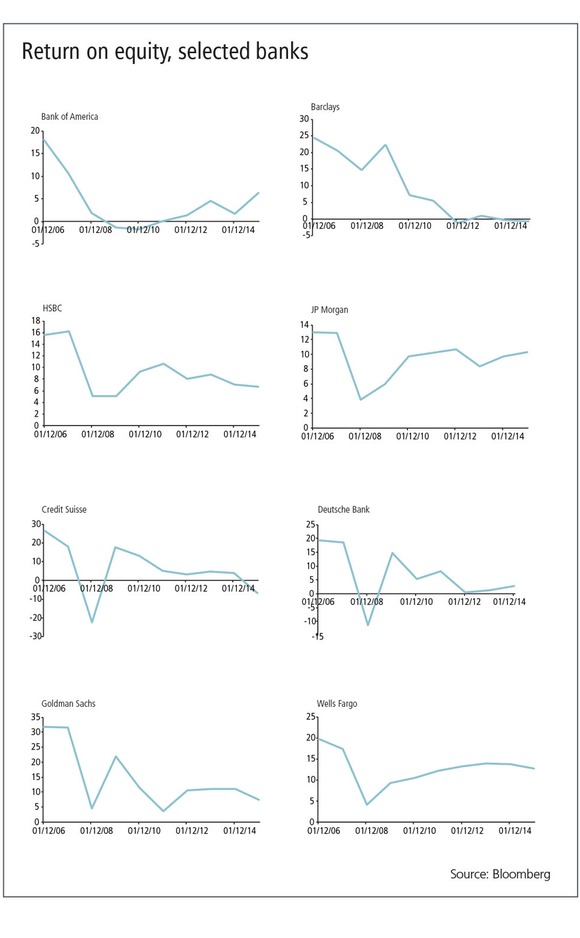

Professional stock-watchers say the new rules are one of the reasons bank valuations are depressed and share prices are more volatile (see figure 1) – reinforcing the impact of the ongoing economic drift. Some investors, meanwhile, have stopped trawling through regulatory footnotes and are looking for the writing on the wall: one hedge fund manager argues regulation has turned banks into "turgid utilities" (see box, The ROE collapse).

"Regulatory uncertainty has robbed investors of any confidence in these stocks," says Simon Samuels, a banking consultant and former equity analyst at Barclays. "There's a chance you're going to wake up tomorrow morning and there will be a new rulebook, which means what previously attracted you to the business is no longer attractive."

Nobody cares about the fundamentals. All they care about is the monster under the bed

Richard Bove, equity research analyst at Rafferty Capital Markets

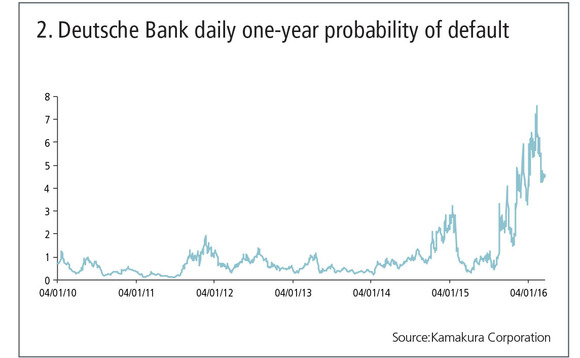

This uncertainty binds banks together as a group – the theory goes – and leaves them all vulnerable to shifts in sentiment, a faultline that radiates from the post-crisis reform project, and might also undermine it. Stock prices are not just a matter for investors, but also for depositors and credit investors: since the days of CreditMetrics and KMV, popular credit models have used stocks as a key input. As Deutsche Bank's stock cratered during the first two months of this year, its one-year probability of default (PD) – calculated by credit spread modelling specialist, Kamakura – hit a peak of 7.6%, its highest level since 2009 (see figure 2).

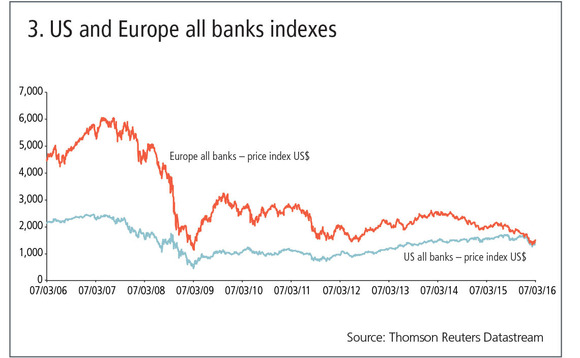

This is just one way in which falling stocks have system-wide implications. And bankers point out that market participants do not need a sophisticated credit-spread model to worry about a tanking stock price (see figure 3).

"Liquidity problems come from a crisis in confidence," says Peter Franklin, senior vice president and director of asset and liability management at Sun Trust. "They are self-fulfilling prophecies. Why did the stock decline? If people feel an institution is insolvent, it becomes ostracised by the financial community, loses access to the markets and will eventually die."

Regulators are not convinced. Andreas Dombret, a member of the executive board at Deutsche Bundesbank, who is responsible for banking and financial supervision, concedes "regulatory uncertainty may contribute" to bank stock volatility, but says it is just one of many factors.

These other factors are a better explanation of the sector's first-quarter woes, he says: "The recent market turbulence was truly global. It was partly driven by revised growth forecasts – especially in emerging economies and China – as well as oil price developments and the interest rate decision by the US Federal Reserve. These developments were accompanied by a downward revision of medium-term inflation expectations, which created a background of uncertainty that enabled small items of news to trigger strong reactions in a particular sector or instrument."

Likewise, Paul Tucker, chair of the Systemic Risk Council and former deputy governor at the Bank of England, identifies three possible causes for the volatility - but in none of these cases "would the regulation of the sector be the cause. Indeed, a more resilient system would be proof against risk" (see box, "We shouldn't care about stocks themselves ..."). And a senior European prudential regulator warns darkly against what he sees as just another lobbying push: "Banks are using this rhetoric now and trying to influence the remaining regulation, and trying to scare regulators and politicians that what they're doing is dangerous for the economy as a whole. That in itself is dangerous."

Bank analysts aren't lobbyists, though – or, at least, they shouldn't be. Their claim is not that banks can't make money, more that the slowly unfurling regulatory bloom makes it difficult to estimate how much money they will make. "It's difficult, and certainly analysts that work out a way of really doing it on a systematic basis will absolutely clean up. There's no publicly available data you can go through to get some things right," says Daniel Davies, managing director of equity at independent research firm Frontline Analysts.

One London-based equity analyst agrees: "I'd love to say it's not challenging to keep on top of this. But banking is a heavily regulated industry, and the uncertainty involved in regulatory developments means we have to be on top of it. Often regulations are written in a way that is quite difficult to penetrate. Reading everything that comes out is a challenge."

In-flight regulations illustrate the point. An international overhaul of trading book capital requirements was published in January, presaging a 40% weighted-average increase in capital for individual banks, according to regulators' best estimates. But the impact depends to a great extent on what method banks use to work out their capital – the more-punitive standardised approach, or the internal models approach, for which regulatory approval is needed at the level of each individual trading desk. As things stand, banks claim the new tests that act as a gateway to the internal model approach will be impossible to pass, and claim capital would jump as much as sixfold if certain businesses had to use the standardised approach.

Or there are the recent proposals that would restrict the use of internal models for loan portfolios – again, banks fear capital will jump significantly for certain types of exposure, from unrated emerging market customers to bog-standard mortgage lending.

Bank disclosures offer some insight into the anticipated impact, but not enough, according to Rafferty's Bove, and the sheer volume of the information contained in quarterly and annual bank disclosures in the US – known as 10K and 10Q reports – makes it hard to digest.

How am I supposed to say that because there's a household credit demand of 8%, it means that for macro-prudential reasons they will increase the floor to 25%? It's impossible for me or any analyst to quantitatively make that kind of assessment

London-based equity analyst

"In general, it is now impossible to understand a bank balance sheet due to regulations. The 10Ks – which 40 years ago would be very small documents, less than 30 pages – now can easily run to over 300. I follow 36 stocks, of which 20 are banks. Assume the average 10Q runs to 150 pages and the average 10K is 250 pages; I would have to read 3,000 pages for three quarters and 5,000 at year-end, not including press releases, conference call reports and other special notifications like lawsuit transcripts. The math does not work," he says.

In addition, national supervisors have become understandably more willing to take matters into their own hands. This can be hard to foresee, and the impact hard to forecast. As an example, the London-based equity analyst points to the August 2014 decision by Sweden's bank supervisor to hike the risk-weight floor for mortgage exposures from 15% to 25%. Official nervousness about mortgage lending had been well flagged, and the floor itself was first imposed in 2013, but the London-based equity analyst says it was impossible to know from the state of the mortgage market what the precise regulatory response would be.

"The Swedish regulator relatively arbitrarily increased the mortgage risk-weight floor. It was just to cool off the property market, but there was no technical explanation for that increase to 25%. How am I supposed to say that because there's a household credit demand of 8%, it means that for macro-prudential reasons they will increase the floor to 25%? It's impossible for me or any analyst to quantitatively make that kind of assessment," he says.

In a similar vein, four analysts complain about the US Federal Reserve's annual stress-testing regime for large banks – the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) – which penalises banks with a restriction on dividend payments if their stressed capital ratio falls below a certain threshold, but also if the supervisor sees weaknesses in risk management or modelling.

In 2014, when Citi failed this qualitative test, the Fed pointed to deficiencies in its "ability to project revenue and losses under a stressful scenario for material parts of the firm's global operations, and its ability to develop scenarios for its internal stress testing that adequately reflect and stress its full range of business activities and exposures." These kinds of failings are tricky for an outsider to spot, analysts say – and if analysts are struggling, then it seems fair to assume investors are, too.

Some support for that assumption can be found in bank valuations - a point not lost on bankers themselves. After listing a host of regulatory pressures and their uncertain aggregate impact, JP Morgan chief executive Jamie Dimon concluded in his 2014 letter to shareholders: "Given that much uncertainty, which is greater for JPMorgan Chase than for most other banks, it is understandable that people would pay less for our earnings than they otherwise might pay."

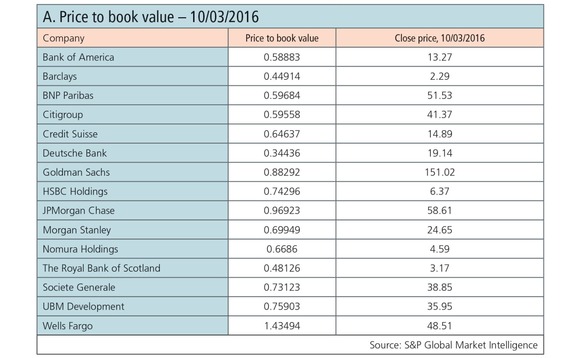

Price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples are depressed across the industry, indicating a lack of confidence in the growth of bank profits. A different - and potentially more worrying – message comes across in price-to-book ratios (see table A). As of early March only Wells Fargo, among 15 large banks, had a ratio above 1: Deutsche Bank was the lowest at 0.34, with JP Morgan second highest at 0.97.

"A discount to book value might imply the market believes the sector faces massive, impending losses. Those losses might come through in the lending book, in credit losses, or via litigation and redress costs. There is a concern that litigation may drive banks to make substantial losses, which erodes the book value," says Samuels, the banking consultant.

Analysts see a direct link between this kind of uncertainty and bank stock fragility: "I think the volatility has a lot to do with regulatory risk," says Davies of Frontline Analysts. Samuels says regulation has been "the single biggest driver of share prices in the sector" for nearly 10 years.

For those who buy this line of thinking – and not everybody does – the next question is whether it matters. Does anyone need to care?

The answer depends how far you take the argument: depressed valuations seem like a matter for shareholders only. But if bank stocks are also more prone to savage sell-offs, then it opens the door to twin systemic concerns – that the cost of equity and debt capital will increase for the industry, with knock-on cost increases for all users of bank financing and intermediation; and that a short-term lack of confidence in one or more banks could, with a push from elsewhere, turn into panic and collapse.

"There is a connection between the equity markets and the credit markets, and the sell-off in bank stocks at the start of the year also produced a huge discount in the credit instruments of several investment banks. That, of course, impacts their ability to fund themselves, which could become a liquidity problem. And then it's an immediate, tangible problem for the bank," says the London-based equity analyst.

A prudential regulator makes the same point: "To an extent, this is what we saw at the start of the year, when there were concerns – valid or not – about one big continental bank, and the stock market response prompted people to think: ‘Oh my God, maybe there's a bigger problem than we thought.' The danger is that it becomes self-perpetuating."

Not enough

In theory, tougher regulation heads off that danger – banks are less risky, and are more able to deal with both capital losses and liquidity pressure, so a death spiral should not have the chance to gather momentum. In practice, tougher regulation may not be enough. Investors are unlikely ever to believe banks are bulletproof, so another line of defence is needed as well – banks have to be successful.

Writing in Risk.net in March, Paul Fisher, an executive director with the Bank of England, made the point that: "Regulators need firms to be profitable. As a prudential supervisor, perhaps the worst situation is when your firm isn't making any money."

A bank that is both strong and profitable can endure periods of doubt – and panic should never have a chance to set in. It also has the ability to bolster its defences, when needed, whether that is a consequence of growth or of deteriorating economic conditions.

"If you ever want the bank to raise capital, you want it to be in a situation where there's some demand for those shares. One of the things that scared regulators the most over the past 10 years was when UniCredit had to get a rights issue away in 2012, and for about a week or so there was a real question as to whether the stock market was going to provide that money on any terms at all," says another London-based analyst.

The New York-based policy expert at one international bank makes a similar point: "There are long-term implications of equity market weakness. Is this an industry that can attract capital, or is it one that needs to shrink? When your stock trades at a significant discount, there is significant pressure to shrink your footprint and try to relieve some of the pressure."

This is where charges about regulatory risk and its impact on bank stocks are hardest to bat away: somewhere, tangled up with fears about China, monetary policy, interest rates and growth, there may be persistent questions about the impact of regulation. The hope has to be that those questions will fade with time.

"We shouldn't care about stocks themselves ..."

Risk asked current and former regulators whether they agreed that post-crisis regulation is making bank stocks weaker – and whether stock volatility is a prudential consideration. The responses were varied.

Andreas Dombret, a member of the executive board of the Deutsche Bundesbank: "Overall, I would assign greater importance for bank stocks' volatility to macro or firm-specific developments. But regulatory uncertainty may contribute to it. I believe there is still potential to harmonise regulation and its application in the supervisory process in order to ensure equal treatment and thus clarify investors' expectations."

One senior European prudential regulator: "I think we shouldn't care about stocks themselves, because that's the problem of shareholders, but it's a relevant indicator of a bank's underlying resilience – one of the indicators – and markets seem to be efficient in discerning a difference between institutions. They're not all the same – it seems like those banks with low risk-weighted capital and leverage ratios were hit hardest at the start of the year."

My view is you can't attribute the volatility to regulatory uncertainty, though, because this regulatory process has been going on for at least six years now. And all of a sudden this is the scapegoat for everything that might go wrong with the market and with banks' performance. It doesn't seem convincing to me. We're seeing an overall downturn for banks, and the macro outlook has been dampened."

Paul Tucker, chair of the Systemic Risk Council and former deputy governor at the Bank of England: "The volatility might reflect concerns that parts of the European banking system are vulnerable to the global economic environment, or uncertainty about business models if past results simply reflected excessive leverage and so elastic balance sheets. In neither case would the regulation of the sector be the cause. Indeed, a more resilient system would be proof against risk. If the new resolution regimes are credible, which they definitely can be, the cost of debt issuance might rise, because the government subsidy should have gone. That in a way was one goal of the reforms."

The argument that greater regulation makes banks unprofitable – it's hard to see how it works. They would just pass it on to the economy. At most, it would make banks low risk and therefore their return on equity would be lower, but their cost of capital would be lower as well because people would need compensating for less risk."

The ROE collapse

Banks are important, and lots of people and businesses rely on them, and they need to be tightly regulated. The same is true of utilities. So, does that mean banks and utilities should generate the same kind of returns?

The comparison has been drawn many times during the post-crisis reform push, but it currently has added bite because return on equity (ROE) at the largest banks has collapsed in the past decade. Taking Morgan Stanley as an example, 2006 saw the firm post a 23.5% ROE, which fell to 9.7% in the first year of the crisis - since then, it has not once been in double-digits, according to data from Bloomberg.

Bank chief executives continue to aspire to ROEs of 12% and more, but investors are split on whether that is possible – in part, because there is a perception that the new prudential framework is designed to prevent it.

The chief executive at one New York-based hedge fund that used to trade the sector now describes banks as "turgid utilities" and says long-run ROEs are likely to be in the 6%–8% range (see charts below).

"I think there are some regulators that would like banks to be utilities, because that certainly makes their life simpler," says a policy expert at an international bank. "A regulator doesn't get blamed so much if the economy's slow, but will get 100% of the heat if a bank on their watch fails. Regulators really want a quieter life, and in some ways I can't blame them. But trying to drain all the risk out of the financial sector also means you're draining a lot of the risk capital out of the financial system. If you want to have economies grow, you're going to need people who take some risks. Maybe utility banks are safer - but they will also be less useful for the rest of the economy."

Ian Tabberer, an investment manager in the global equities team at Henderson, says some investors will be put off by utility-style banks: "The problem is that if regulators incentivise management teams to become utility-like, then they won't take risk in lending. We need banks to take risk in lending to support economic growth. So I'm not sure that's a great business model or one that's all that attractive to investors," he says. "Banking is a risk business - without risk, there is unlikely to be sufficient reward to provide a commensurate return on equity for long-term investors,"

A senior official at one European supervisor says regulations were not designed to turn banks into utilities - but believes that has been the outcome.

"I don't think it was the intention, but I would say it's an unavoidable consequence. If you want to reduce risk, then of course bank stocks probably would be less exciting," he says. "Only stable banks, boring banks, can fulfil their systemically important functions. If boring is a more efficient, more stable, long-term orientated system, then definitely that's how banks should be."

Paul Tucker, senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, contests the banks' claims: "Of course banks whose past profitability was an illusion created by a leveraged credit boom might now charge more for credit or pay less on deposits; that is, a higher return on assets and from their core business. Suggestions that the post-reform banks are utilities are misleading. The authorities did not go for ‘narrow banking', with all assets risk-free."

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Regulation

Hopes rise for cross-product netting under SA-CCR

Banks want rule change in Basel III endgame to lower capital costs of clearing UST repos

Long way round: EU banks lament credit spread saga

EBA ditches some of banks’ preferred qualitative reasonings – and shortcuts – for CSRBB exclusion

Iosco chief sees no need for CCPs to hold more capital

CCPs have shown resilience in volatile times without extra skin-in-the-game, says Buenaventura

Banks urge EBA to delay risk benchmarking amid Iran conflict

Risk managers say hypothetical portfolio exercise clashes with severe market turbulence

EU officials tamp down hopes for bank capital relief

Capital cuts are not a done deal in EC’s review of competitiveness, despite US deregulation

EU regulators clash over ceding supervision to Esma

Belgian and Spanish regulators differ on drive for centralised oversight of cross-border firms

Why Trump’s latest Truth should make TradFi twitchy

Wall Street is becoming the villain in US president’s crypto movie

EBA guidance prompts banks to rethink CSRBB perimeters

Banks will likely have to expand their credit spread risk coverage following recommendations