Hedge funds, securitisation and leverage change P2P game

Overwhelming institutional demand, hedge funds with a double-digit share of the market’s assets, trendy approaches to underwriting, a nascent securitisation market – these are the forces shaping the peer-to-peer lending business in the US, and some observers are starting to worry. Kris Devasabai reports

For many people, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending probably conjures up images of amateur investors, bright-eyed millennials, and mom-and-pop savers wiring money directly to entrepreneurial individuals and small businesses – a revolution from which banks and other institutions are frozen out.

Many people are wrong. In the US at least, institutional capital is flooding into the P2P market, bringing with it concepts such as securitisation, loan trading, high-speed algorithms and bulk deals, as well as fears that all of this might be happening too quickly for the platforms at its heart.

"Some hedge funds have acquired large portfolios of P2P loans and they're securitising them to obtain leverage, so they can take an 8% unleveraged return and turn it into a 16% or 24% return. That creates some unique misalignments of interest. The originators and servicers – the P2P platforms – don't have much experience across market cycles and they don't have skin in the game. The whole thing has shades of the subprime mortgage crisis," says the head of structured credit at a large bank in New York.

According to regulatory filings, Colchis Capital Management, a hedge fund based in San Francisco, had $663 million of P2P loan investments at the end of June – equivalent to 10% of all loans originated by the sector in the US. Garrison Investment Group, a $3.2 billion credit firm, has also accumulated large amounts of P2P loans, according to industry sources. Colchis declined to comment for this article; Garrison did not respond to requests for comment.

"Peer-to-peer lending has turned into hedge fund-to-consumer lending," says the head of structured credit at a large bank in New York. Some in the business admit P2P is now a misnomer and suggest rebranding it as marketplace lending (see box, High-frequency lending).

It isn't just hedge funds. During the last quarter, almost 60% of the $1.1 billion in loans originated on California-based Lending Club – the largest P2P lender in the US – were snapped up by asset managers, banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, pension funds and other institutions (see box, Reintermediation – banks get in on the P2P boom). At Lending Club's main competitor, Prosper Marketplace, 66% of loans went to these same types of investors.

Originators and servicers – the P2P platforms – don't have much experience across market cycles and they don't have skin in the game. The whole thing has shades of the subprime mortgage crisis

BlackRock, which has equity stakes in Lending Club and Prosper, has bought 20-25% of the loans originated on the latter in recent months, according to market participants. BlackRock declined to comment on its P2P loan investments.

"The demand is insatiable," says Aaron Vermut, chief executive officer of Prosper. "I get calls from investors all the time. Retail wants more, high net worth wants more, institutional wants more – everybody wants more."

So, why are institutions flocking to P2P loans and, more importantly, what are the risk implications? The first question is easy enough to answer. Investors can earn interest of anywhere from 6% to as much as 35% on three- to five-year P2P loans, compared with below 5% on high-yield and other comparable credits.

"Investors have a choice between short-duration single B-rated high-yield paper at 3% or the safest three-year P2P loans at 6–8%. The smart money can see P2P is cheap and they want to buy as much as they can," says Brian Weinstein, a principal at Blue Elephant Capital Management, an asset manager in New York specialising in online lending. He was formerly a managing director of BlackRock's fixed-income group.

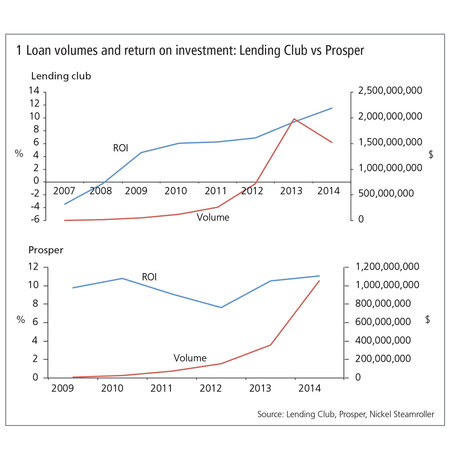

The deluge of institutional money has allowed P2P lending platforms to rapidly scale up their operations, becoming credible competition for credit card companies and traditional bank lenders. Lending Club and Prosper made $2.4 billion in loans in 2013, compared with only $881 million in 2012, and are on course to originate around $6 billion this year.

Lending Club filed for an initial public offering (IPO) in August and the share sale is expected to value the company at more than $4 billion. The company declined to comment for this article, citing the pre-IPO quiet period.

Loan volumes are not growing fast enough to satisfy yield-hungry institutions, however. Peer-to-peer investors could absorb "10 times" the current loan volume on Lending Club and Prosper, according to Peter Renton, co-founder of Lend Academy Investments in Denver, Colorado. "But, originating that many loans would put a tremendous amount of stress on the technology, operations, infrastructure and underwriting capabilities of the online platforms. That's where the constraint is. The investor capital is there," he says.

This is where the risk comes in. Among cynics, the fear is that P2P lenders will ramp up origination before the strengths and weaknesses of their underwriting methods are properly understood, or simply lower underwriting standards, so repeating the mistakes that helped to fuel the subprime mortgage crisis.

The overwhelming demand has already given rise to a number of P2P securitisations; the first in October 2013, when New York-based hedge fund manager Eaglewood Capital closed a $53 million deal in which a large reinsurer was said to have bought all of the senior paper. A number of other private transactions followed, before the first deal to be publicly rated by one of the big three rating agencies – in this case Standard & Poor's (S&P) – in July this year (see box, Securitisation – the deals so far). The lender was online student loan-refinancing specialist SoFi.

Some believe the SoFi deal augurs well for P2P securitisation as it could open up the asset class to banks, insurers and pension funds in a major way. "Closing the first rated securitisation was the biggest challenge. Now we have the first S&P-rated securitisation, it will be smoother and faster to do the next one. I expect to see the first rated securitisation of Lending Club or Prosper loans in the next 18 months, and that will open the floodgates for other securitisations to receive ratings," says Jonathan Barlow, founder and chief executive of Eaglewood Capital Management in New York.

That is if nothing goes wrong in the meantime, of course. Some lenders are already warning investors may have set their return expectations too high. Investors and asset managers often tout 10–12% returns on their P2P loan investments without leverage. This is true for portfolios of loans acquired in the past 18 months, but Alan Schiffres, chief credit officer at Florida-based consumer-lending platform CircleBack Lending, which launched in July 2013, says such high returns are unsustainable in the long term. "The fact is 95% of your profit comes in the first year," he says.

For a diversified portfolio of three-year P2P loans, monthly returns turn negative after 18 to 20 months and completely crater in the final four months, he says. This is because the portfolio tilts towards weaker and delinquent credits over time as stronger borrowers prepay. Schiffres estimates the average return over the life of a portfolio of 36-month loans originated on the main P2P platforms is likely to be around 6–7% – significantly less than the low double-digit gains most investors are shooting for. CircleBack claims it can generate returns of 8–10% with careful loan selection.

This could be a problem for hedge funds that employ leverage and hold the junior tranches of securitisations. Leverage is freely available from institutions such as Capital One, Citi and Jefferies, according to market participants. These credit and warehouse lines come with various covenants related to the average Fico score, debt-to-income ratios and other characteristics of the investor's loan portfolio. A fund that employs leverage needs to continuously reinvest prepayment proceeds and new subscription monies in the best new originations to maintain the quality of the portfolio. But, if performance dips – for instance, if the junior tranches of legacy securitisations start seeing big losses – and investors head for the exits – any prepayment proceeds will be used to pay out redemptions, leaving the fund short of capital to buy new assets and satisfy its covenants.

"That's the risk attached to leverage and warehouse lines, especially in a very illiquid asset class such as this. It can be a recipe for disaster," says a hedge fund manager in New York.

The risk of investors stampeding for the exits is elevated with consumer credit, which tends to be highly auto-correlated. "If you get a negative return one month, you can be sure it will be negative next month," says the hedge fund manager, adding that P2P funds running with leverage should be setting investor gates and lock-ups to avoid any liquidity mismatches.

For their part, the platforms say they are aware of the potential risks. Peer-to-peer hedge funds are running with modest leverage of two or three to one, according to Prosper's Vermut. "It's only a risk if all our investors are getting leverage from the same banks. We monitor the amount of leverage on the platform and work with the leverage providers to control that," he says.

What of the underwriting? To traditionalists, some of it looks quirky at best. Peer-to-peer platforms start with consumer credit risk scores, credit histories and debt-to-income ratios, and augment this – to varying degrees – with other data sources and analytics. In some cases, this comes from online search histories, social media and other web data. The algorithms that determine a borrower's creditworthiness are proprietary and closely guarded by the platforms.

Prosper uses credit scores and other standard consumer risk indicators as its base for determining eligibility and pricing. This is supplemented by a proprietary loss-forecasting model called the Prosper Score, which Vermut refers to as the "family jewel".

The proprietary modelling incorporates factors such as online referral channels. A borrower who arrives at Prosper via a debt education site may qualify for a cheaper rate. "We have data showing people coming from those sites repay loans at a lower loss rate. We use that information in pricing," he says.

Prosper also has a team of data scientists who analyse factors such as credit availability and investor demand to inform pricing, although Vermut stresses the firm is not trying to predict macro factors such as employment and benchmark interest rates when setting loan rates.

Lending Club's approach is more straightforward and focuses on Fico scores, debt-to-income ratios and credit histories to price loans, according to sources.

Other P2P lenders use ‘big data' explicitly to determine the risk of borrowers instead of relying on consumer credit scores. New York-based OnDeck, which specialises in small business loans, uses reviews on Yelp and Google Places as inputs in its underwriting model. One platform claims its machine-learning algorithm analyses 15,000 pieces of social media data to price loans, according to an investor in P2P loans.

Even within the industry, this does not sit well with everyone. "Some people are doing this with a purely computer-driven approach that emphasises machine-learning algorithms and big data over traditional credit underwriting. We think that could be problematic," says Michael Solomon, chief executive of CircleBack Lending. He adds that the company relies on "tried and true" underwriting methodologies. Its chief credit officer, Schiffres, is a veteran of the credit card divisions of Citicorp, Dean Witter and American Express.

Those concerns are shared by some of the bigger investors in P2P loans. "We have almost no transparency into those algorithms. I'm not sure if some of the platforms themselves understand exactly what their machine-learning algorithms are doing," says a source at one firm.

Texas-based Titan Bank has been buying high-quality loans from Lending Club and Prosper for more than a year. Jonathan Morris, president of Titan's holding company, BMC Bancshares, says "many new platforms are playing Wizard of Oz" with their black box underwriting methodologies. "We question how they're using social media data for scoring. There are numerous regulations that restrict the use of this type of data in credit underwriting."

In a note discussing P2P securitisations, S&P also cited "ongoing concerns with the quality and consistency of the loan-underwriting process, as well as with the robustness of the data these systems collect and maintain".

Some P2P platforms have adjusted their underwriting criteria, allowing them to serve riskier borrowers. Lending Club requires people to have Fico credit scores of above 660 to qualify for its loans. However, last year it started catering to subprime borrowers with scores of between 640 and 660, as well as small businesses. While these so-called ‘policy 2' loans are only available to certain investors – essentially institutions and wealthy individuals – they accounted for nearly 30% of Lending Club's originations in the second quarter. Santander Consumer USA is said to be the main purchaser of these loans.

Prosper has offered loans to borrowers with Fico scores above 640 from the outset, but Vermut says the firm is committed to maintaining high underwriting standards. "The risk modelling is the most important thing we do here – the credit underwriting, pricing and net-loss forecasting. You can't go from a standing start to originating tens of billions of dollars a year. You have to collect the data and build the capacity to verify and underwrite the loans. That's what we're doing. We are growing fast, but we're growing responsibly and making sure these loans perform the way our investors expect them to," he says.

Lend Academy Investments' Renton sees no evidence of underwriting standards on the main platforms slipping over the past 18 months. "The Fico scores, default rates and returns have remained fairly consistent over this period of rapid growth," he says.

Still, he concedes most investors have little idea of what will happen if credit conditions deteriorate. "This is still a relatively new industry. These companies were in their infancy in the crisis and we haven't gone through a full cycle, so the truth is we don't know what would happen in a downturn. But I personally believe the underwriting is robust and that P2P loans will perform better than other investments if we have another financial crisis," says Renton.

Leverage and securitisation undoubtedly have a role to play in P2P lending, as they do in almost all segments of the credit markets. "The fact is most investors are not interested in an 8% return. You need securitisation to reach a diverse investor group," says a senior executive at one online lending platform.

At the same time, most platforms are wary of putting their fate in the hands of leveraged hedge funds with an eye on securitisation. Prosper aims to cultivate an investor base that is equally split across three constituencies: retail investors; wealth managers or investment advisers; and institutions.

"We want lender diversity," says Vermut. To that end, Prosper is working on launching new tools and index products that will make it easier for retail investors to acquire its loans. "We are in this for the long run, so we are very concerned about lender diversity, correlation of investors and leverage. Those are issues we will continue to focus on as we grow the business," he adds.

As competition for peer-to-peer loans (P2P) has grown, some investors have turned to technology to help them fill their portfolios, using algorithms that scour platforms and automatically bid on loans that meet the right criteria. This has given rise to concerns that retail investors are not getting a fair crack of the whip.

"Peer-to-peer investing has developed into a quantitative, programmatic and automated field," says Angela Ceresnie, co-founder and chief financial officer at New York-based Orchard Platform, which provides connectivity and back-office services to P2P originators and investors. She says institutional investors are buying too many P2P loans – which have an average size of $15,000 – to be able to select each one manually, while alpha-seeking asset managers see speed as a way to differentiate themselves on loan selection.

The P2P lending platforms have pushed back against some of this. Prosper Marketplace allocates a "demonstrably random selection of loans" to its fractional pool for retail investors and a whole loan programme for institutions to ensure bigger players are not cherry-picking the best borrowers. Investors are also limited to buying 10% of the fractional loans, so it is difficult for big firms to dominate that platform.

Prosper also applies a "speed limit" for its market, capping the number of times an investor can ping its platform each second. "We didn't want a high-frequency trading problem, so we nipped it in the bud," says Aaron Vermut, the platform's chief executive.

Lending Club and other P2P platforms catering for retail investors have instituted similar measures.

Reintermediation – banks get in on the P2P boom

In the simplest version of the peer-to-peer (P2P) lending story, banks are the losers, cut out of business that could have been theirs, with the internet providing a more efficient distribution mechanism than traditional lenders are able to offer. But that implies banks are simply sitting on the sidelines.

In fact, Lending Club has struck deals with regional and community banks such as Congressional Bank in Maryland, Titan Bank in Texas and Union Bank in California to purchase its loans and even refer customers. Union Bank is the 23rd-largest bank in the US.

Titan Bank has been purchasing the highest-quality loans on Lending Club and Prosper for a little over a year. "This was a great way for us to get exposure to consumer loans that weren't walking in through the branch network in a low-cost manner," says Jonathan Morris, president of BMC Bancshares, the holding company of Titan. Loan performance to date has been in line with the firm's internal projections, he adds.

Last March, Santander Consumer USA, the subprime auto-lending arm of the Spanish banking giant, cut a deal to acquire up to 25% of the loans originating on Lending Club.

Funding Circle, an online market for small business loans, has an agreement with Santander in the UK to refer customers the bank cannot fund because they do not fit its underwriting model. "We believe Funding Circle and banks are complementary sources of finance. The partnerships we're seeing between online lenders and traditional financial firms are a validation of this model," says Albert Periu, director of capital markets in the US division of Funding Circle.

In the boldest move to date, SunTrust Banks, the seventeenth-largest bank in the US, has launched its own P2P lending platform, called LightStream. The loans are funded by SunTrust, rather than investors. The bank declined to comment on the venture.

P2P securitisation – the deals so far

Eaglewood Capital, a New York-based hedge fund manager, completed a $53 million securitisation of Lending Club loans in October 2013 in a first-of-its-kind transaction. A large global reinsurance company bought all the senior tranches. The deal was upsized to $100 million in May this year.

Garrison Investment Group, a middle-market credit and asset-based investor, sold a $150 million securitisation of Prosper Marketplace loans in July this year, with JP Morgan's wealth-management arm rumoured to be the sole investor in the senior tranches.

OnDeck, which lends to small firms, completed the first securitisation of online-originated small business loans in April. The $175 million deal was snapped up by insurance companies and asset managers.

In another first, SoFi, an online lender specialising in refinancing student debt, closed the first P2P securitisation to receive a rating from one of the big three credit-rating agencies. Standard & Poor's (S&P) gave the senior tranches of the $251 million deal an A rating. SoFi previously closed a $152 million securitisation rated by DBRS in December 2013.

There is more to come. Jefferies, the middle-market investment bank, has a deal with CircleBack Lending, an online consumer-lending platform aimed at institutional investors, to acquire up to $500 million of its loans. The bank is expected to securitise the loans, and sell them to big insurers and asset managers.

Several hedge funds are also gearing up to securitise their P2P loan portfolios, following in the footsteps of Eaglewood and Garrison.

Much depends on the co-operation of the big three credit-rating agencies. So far, they have been cautious about rating any deals issued by hedge funds. S&P published a note in April highlighting various hurdles to be cleared, including the need for data on P2P loan performance over a full economic cycle, concerns over the quality and consistency of the underwriting process, and regulatory risks.

S&P's decision to rate the SoFi securitisation led to speculation the rating agency had softened its stance. However, it says the SoFi deal had some unique characteristics to differentiate it from run-of-the-mill P2P securitisations, such as the credit quality of the loans, sponsorship from the originator and the involvement of experienced servicers.

In its ratings report, S&P also notes that "while SoFi's original business model relied on accredited alumni and other individual investors to fund its loan originations (a P2P platform), SoFi is now primarily funding itself with customary institutional and bank financing". According to the report, SoFi had $230 million of forward loan participation commitments from depository institutions and $241 million of borrowing capacity with four warehouse lenders.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Risk management

Bank ALM tech still dominated by manual workflows

Batch processing and Excel files still pervade, with only one in four lenders planning tech upgrades

Many banks ignore spectre of SVB in liquidity stress tests

In ALM Benchmarking exercise, majority of banks have no internal tests focusing on stress horizons of less than 30 days

Quant Finance Master’s Guide 2026

Risk.net’s guide to the world’s leading quant master’s programmes, with the top 25 schools ranked

ALM Benchmarking: explore the data

View interactive charts from Risk.net’s 46-bank study, covering ALM governance, balance-sheet strategy, stress-testing, technology and regulation

Staff, survival days, models – where banks split on ALM

Liquidity and rate risks are as old as banking; but the 46 banks in our benchmarking study have different ways to manage them

CME faces battle for clients after Treasuries clearing approval

Some members not ready to commit to 2026 start date; rival FICC enhances services

AI and the next era of Apac compliance

How Apac compliance leaders are preparing for the next era of AI-driven oversight

Responsible AI is about payoffs as much as principles

How one firm cut loan processing times and improved fraud detection without compromising on governance