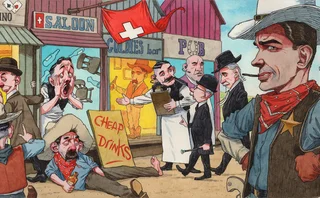

How Credit Suisse fell victim to its own success

The roots of the Archegos loss can be traced to a business strategy the bank embraced back in 2006

When Archegos Capital Management imploded in March, its prime brokers seemed surprised to learn the $10 billion family office had made similar trades with several other banks.

Perhaps they shouldn’t have been – least of all Credit Suisse.

The Swiss bank practically invented the multi-prime model, whereby hedge funds spread their positions among multiple counterparties.

Back in 2006, Credit Suisse worked with technology vendor Paladyne Systems to create an open architecture middle- and back-office system that made it easier for hedge funds to add or switch prime brokers at will. The technology was a critical component of a broader strategy – devised by the bank’s then-head of prime services, Phil Vasan – to peel away customers from the duopoly of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

The bet on multi-priming paid off in spades after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which trapped billions of dollars in hedge fund assets in years of bankruptcy proceedings. As clients of other US broker-dealers, including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, sought safer havens for their assets, Credit Suisse emerged as one of the big winners.

The bank backed up its technology edge with a clever marketing strategy. The prime services desk created a list of prominent hedge funds it wanted to do business with, called the CS400. When a report in The Wall Street Journal revealed the existence of the list, Credit Suisse was flooded with calls from hedge funds asking if they were on the list – and if not, how to get on it.

“Our phone rang off the hook,” says one former Credit Suisse prime brokerage executive. “We got all the business we could handle, and we had to turn people away.”

By 2010, Credit Suisse was ranked by data provider Hedge Fund Intelligence as the world’s second-largest prime broker, behind Goldman Sachs. Its client list included many of the biggest names in the hedge fund industry at the time – among them, Tiger Asia, the former hedge fund of Archegos founder Bill Hwang.

Paladyne was acquired by Broadridge in 2011, and the system it built with Credit Suisse is still widely used by hedge funds to connect to multiple prime brokers.

But the momentum behind Credit Suisse’s prime services business would eventually fade. After leading the division for a decade, Vasan was tapped to run the bank’s US private banking operations in 2013. Three years later, he left to join BlackRock.

Vasan’s departure threw Credit Suisse’s prime services division into a state of flux. Six different heads presided over the unit in the following eight years. The bank slipped in the rankings – in 2020, it was the world’s fifth-largest prime broker by funds serviced, according to an April survey by Preqin – and seemed to lose its technology edge during a period of cost-cutting.

Credit Suisse is understood to have used a static model – a technology that one bank risk manager describes as “very 1980s” – to calculate margin requirements for the Archegos portfolio, which it set at just 10%.

But many of the bank’s problems can be traced back to a lack of visibility into Archegos’s overall portfolio. By trading swaps, which are exempt from disclosure rules that apply to securities holdings, and spreading them around a number of dealers, Archegos was able to keep the true scale of its exposures – said to be in excess of $60 billion – largely hidden from its counterparties, until it was too late.

A decade-and-a-half after pioneering the multi-prime model, which catapulted the bank into the big leagues of prime brokerage, Credit Suisse has now paid a heavy price for the lack of transparency that came with it.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Our take

Hedge funds must race the clock to check their dealer-rule status

Working out whether a firm is caught by SEC registration requirement could take months

Filling gaps in market data with optimal transport

Julius Baer quant proposes novel way to generate accurate prices for illiquid maturities

Why Europe still awaits a private credit CLO

Tricky questions face managers that plan to launch the structure on the continent

The signs of tacit collusion in the dividend play trade

Game theory and real-world data point to a different understanding of how arbitrage in markets works

Decades of history says you can beat high inflation with quality

Factors such as momentum and value generally outperform the market irrespective of inflation, but new research suggests quality stocks are best when prices are rising rapidly

Esma faces tough task in implementing Emir 3.0

EU regulator must contend with tight timeframes and increasing workload without additional resources

Quants are using language models to map what causes what

GPT-4 does a surprisingly good job of separating causation from correlation

China stock sell-off will test securities firms’ risk managers

Regulatory measures to support stock market could add to risks facing securities sector