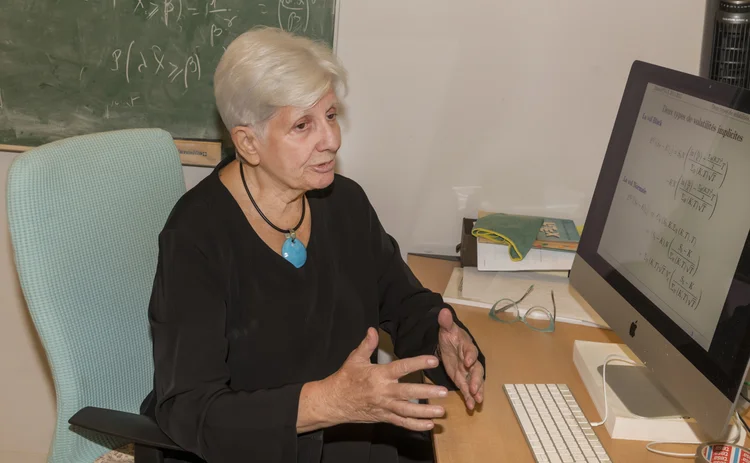

Lifetime achievement award: Nicole El Karoui

Risk Awards 2024: Mathematician had to swim against the tide to create first – and most famous – master’s in quant finance

As summer drew to a close, a flurry of heartfelt posts appeared on LinkedIn from students who had won a place on a particular master’s course. They were variously proud, thrilled, delighted and pleased. They wrote about their journeys, their aspirations. “Hard work leads to everything,” one said. And scores of people in their personal networks wrote back, congratulating them, sharing their joy, and posting bicep-flexing emojis.

The course in question is a special one. It may be the only one of its kind to be widely recognised by a nickname. The students called it the “DEA El Karoui” – the first part being a French acronym for the equivalent of a master’s degree, and the second being the name of one of its co-founders, the mathematician Nicole El Karoui.

Formally known as the master’s in probability and finance, the course is offered by Paris-Sorbonne University in conjunction with the École Polytechnique. It is thought to have been the first master’s degree to allow maths and other technical graduates to specialise in quantitative finance – the first purpose-built bridge from academia to bank trading floors, buy-side front offices, and other roles that require both a knowledge of markets and a deep knowledge of maths. Among the dozens of copycat courses that have sprung up since its launch in 1989, the DEA El Karoui still enjoys a special status and – in a market that has come to be dominated by the big US schools – it remains one of the best.

El Karoui isn’t taking the credit, though.

“It’s not my doing. It’s because we have very good students,” she says, speaking from the office that has been hers for the past two decades, at the Jussieu campus in Paris, home to the Sorbonne’s science faculty.

Then she backtracks a little. “I am a realist. We can say the course did a good job of adapting to the moment. But without excellent students, it would not have the same reputation.”

She transformed me. It was amazing

Samuel Wisnia, deputy CIO at Eisler Capital, and a 1996 graduate of the DEA El Karoui

This is typical of her, according to colleagues, friends and former students. El Karoui is humble, they say – she has never sought the spotlight. As a result, some say she has not enjoyed the wider recognition her achievements deserve.

But those who know, know. Former students, colleagues and friends give El Karoui the credit she declines to take for herself, painting a picture of a uniquely talented mathematician, whose vision and philosophy both inspired and changed them.

“She transformed me. It was amazing,” says Samuel Wisnia, a 1996 graduate of the DEA El Karoui who went on to lead the strats group at Goldman Sachs, before heading up macro trading at Deutsche Bank. In 2018, he became deputy chief investment officer at Eisler Capital, the multi-strategy fund founded by fellow Goldman alum, Ed Eisler.

The transformation was two-fold, Wisnia says. El Karoui encouraged him to ask questions rather than soaking up knowledge, and showed him how to use mathematics to solve problems in finance – the latter may sound like table-stakes for a quant finance course, but many of those who spoke to Risk.net for this article believe formal education often fails to help students apply their skills. (More on this later.)

Amal Moussa also landed at Goldman, after graduating a decade behind Wisnia. She is now a managing director in charge of single-stock exotics in New York, and teaches a course as part of Columbia University’s quant finance master’s degree.

The Goldman job must keep her busy. So, why does she teach?

“I think it comes back to that master’s programme,” says Moussa. “I wanted to bring the practitioner’s view to those quant finance programmes – to bridge the gap between the theoretical, academic topics and the practical needs of the industry. I was inspired by Nicole, because she did exactly that.”

Back on LinkedIn, the DEA El Karoui doesn’t just appear in posts from each year’s new intake. Past graduates often namecheck it on their profile pages – sometimes even in the brief slug of text that is normally reserved for a job title. These former students are now at Amundi, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Citadel, Deutsche Bank, DRW, Pimco, Societe Generale, Standard Chartered, Two Sigma – and more, and more.

The list goes on, the names and faces flick past. At its peak, the programme was accepting around 100 students each year.

“The legacy is enormous,” says Lorenzo Bergomi, a former Risk.net quant of the year, who spent more than two decades at Societe Generale – hiring more than a dozen of El Karoui graduates in the process – and is now with quant investor Squarepoint Capital. “She was instrumental in building that ecosystem between academia and banks, one of the very few people – at least in France – who was able to bridge that gap. And it has a lot to do with her personal qualities. She’s very personable, she maintains good relationships with a lot of people, and that’s how she kept abreast of what was going on. She adjusted, and so did the degree she founded.”

In making those changes – to herself, to her course, ultimately to her students – El Karoui also changed the market.

“Girls can’t do maths”

El Karoui was born in Nancy, in the east of France, in 1944 – part of a large family that stood out for its Protestant beliefs in a largely Catholic city. At the time, the distinction mattered.

“When you passed a church, you were supposed to make the sign of the cross. Since we didn’t – because my family was Protestant – the Catholic community explained to the other children that we were heretics. I remember that very well, because there was a church very close to our elementary school, and it stigmatised us in the eyes of the other children,” she says.

These regular reminders that she was part of a minority were ultimately helpful, El Karoui says – it would not be the last time that she was outnumbered.

“In a certain sense, I found it was good to belong to the minority. It was important in the choices I made afterwards, because while respecting the rules of the majority, you don't feel that it represents you; it forces you to identify what is important for you,” she says.

Like all French children in the 1950s, El Karoui attended a single-sex school, discovering an affinity for languages – particularly Greek – and later opting for an intensive introduction to maths, physics and philosophy. She then entered the classes préparatoires aux grandes écoles – a two-year hothouse that prepares students to apply to one of the elite, specialised universities that hand out higher degrees in France. Her focus switched from the humanities to maths, in the expectation that it would give her more career options.

The other big change was that she was surrounded by boys.

“We moved from a class where there were only girls, to a class of 40 boys and only three girls. It was a little difficult,” she says.

El Karoui and her female classmates encountered sexism on a daily basis – they were told that they didn’t belong, that girls could not be good at maths.

“It was very difficult to overcome these comments – these daily comments – even if our results were good,” she says.

El Karoui’s results weren’t always good. She performed well in written tests, but the constant sniping of the boys made her uncomfortable speaking up in class, and she lacked confidence in oral exams.

Despite the hostile environment, and her initial conviction that maths was less interesting than philosophy, El Karoui came to enjoy the subject.

“It was completely different from the maths we studied in secondary school, where the focus was on calculus and ‘geometric’ maths. Now, we introduced real mathematical models, very abstract, where the structure is very important. For me, it was a revelation,” she says.

Now, we introduced real mathematical models, very abstract, where the structure is very important. For me, it was a revelation

Nicole El Karoui

It was the start of a long journey that would eventually lead her to the financial markets. El Karoui completed her two years of preparation, was accepted to study maths at the École Normale Supérieure de Jeunes Filles – a prestigious single-sex grandes écoles that later became co-ed – and continued to be drawn to the more abstract end of the mathematical spectrum, ultimately choosing to specialise in probability theory for the thesis that would win her a professorship in 1971, at the age of 27.

Her focus was not a fashionable one. El Karoui recalls that probability research had a “very bad reputation” among serious mathematicians at the time. But the thesis was a formative experience for her. Focusing on stochastic processes, and working alongside two men, El Karoui came to realise that diversity is important in mathematical research – the trio of researchers had very different personalities, but worked well together for three years. As a result, she also became more confident that her own views mattered, came to believe that she had her own contribution to make.

“It's very important to experience this diversity, because we can all see that maths is very rigid – it has rules that cannot be broken – but that’s not true in research, and when you have different points of view, different reactions, it can be very, very, very efficient,” she says. “It was an exceptional experience. After that I was certain that I would be able to produce good mathematics.”

Of wolves and sheep

In the years that followed, El Karoui got down to work as a researcher and professor. Through the 1970s and 80s, Google Scholar lists 30 papers – mostly co-authored – with a focus on diffusion and Markov processes. It’s hardcore probability theory, with no single focus on where it would be applied.

Then, in 1989, there is a shift. A paper appears on how to price bond options. Shortly after, El Karoui presented work on the Black-Scholes options pricing model; then, the valuation of contingent claims in an incomplete market. A string of papers on interest rate modelling follows.

What happened?

The short answer is that in 1988, El Karoui took a sabbatical and spent it working at Compagnie Bancaire, a consumer lender later acquired by Banque Paribas. Her focus was on credit modelling, but she also heard about derivatives pricing problems during her break from academia and – after a little digging – realised the stochastic mathematics she had spent the past two decades researching was suddenly, urgently relevant in the financial markets.

The wider context is important. The first over-the-counter derivative – the famous cross-currency swap between IBM and the World Bank – had been executed in 1981. The first standard legal documents for OTC trading followed in 1987, as France was launching its futures and options exchanges, Matif and Monep, now part of Euronext.

Even when the master’s was very well-known, I still had to organise everything – the training period, operational issues – without any help from the university, because the opposition was so entrenched

Nicole El Karoui

The first pricing and structuring quants had already made their way onto bank trading floors, but they weren’t trained in financial markets – they were mathematicians, physicists and engineers, who had to find their own way to the industry. In another new development, banks also had access to computers to help run the pricing and valuation models that this first generation of quants was creating.

It was, initially, more artisanal than industrial.

“While I spent this sabbatical semester at the bank, we were using one of the big IBM machines – we had to reserve time to run our calculations,” says El Karoui.

After getting a taste of this three-pronged revolution – in financial instruments, computing power and quant finance – El Karoui returned to her role as a professor at Paris VI University and a researcher at the Laboratory of Probability Theory and Random Models.

“I said to the head of the laboratory that I thought we should develop a programme in this direction – mathematical finance – because it was the first time that stochastic processes were being used directly in the industry, and we were a very big, famous theoretical lab, with a lot of relevant expertise,” says El Karoui.

It didn’t go down well.

Squarepoint’s Bergomi sums up the problem: “In a lot of academic circles people are very, very liberal. In the sense that they hold strong views about – and usually against – markets, capitalism, and associating with banks. At the time, I'm sure she was looked down upon for that. It certainly was not a very comfortable thing to do when you're an academic.”

I said to the head of the laboratory that I thought we should develop a programme in this direction – mathematical finance... The opposition was very strong

Nicole El Karoui

“The opposition was very strong,” El Karoui confirms. “In the maths department, but also in the probability department. People were concerned about the reputational damage. They said we would introduire le loup dans la bergerie.”

Literally translated, the phrase means to put a wolf in the sheep-fold. It gives a better idea of the depth of feeling than its tamer English equivalent, ‘fox in the hen-house’, hinting at the strength and savagery of the banks, the defenceless, ruminative academics, the blood, the baa-ing.

By this point, El Karoui had plenty of experience of being in the minority. She stuck to her guns: “It was a huge opportunity. I was convinced we had to do it.” In the end, the head of the laboratory – the well-known probabilist, Jean Jacod – gave the green light.

That may have been the start of what was to become the DEA El Karoui. It was not the end of the opposition to it. She says it was difficult to persuade some of her colleagues to take on teaching roles for the degree, but eventually she enlisted some business school professors to handle courses on finance and financial markets. Specialist professors took courses on statistics and numerical methods, some of her fellow probabilists taught stochastic calculus and stochastic optimisation (reassured by the notion that they would be focusing on theory), and El Karoui herself led the courses on derivatives pricing and interest rate modelling.

There were around five graduates in the first year of the DEA, El-Karoui recalls, with numbers growing rapidly thereafter. In 2010, the programme minted its thousandth grad, after two decades in which around 50 students were graduating each year.

“It was a remarkable success,” says El Karoui. “But even when the master’s was very well-known, I still had to organise everything – the training period, operational issues – without any help from the university, because the opposition was so entrenched.”

Put the hammer down

There is a big element of right-time-right-place about the success of El Karoui’s degree. With demand for derivatives growing fast, and transistors shrinking fast, human resources became the key constraint. Banks needed a conveyor belt of quants, trained in the relevant maths techniques and an understanding of how to apply them in financial markets.

It wasn’t just timing, though. El Karoui’s course was also well-designed and delivered – and that had a lot to do with her vision and beliefs.

Like most students in the DEA, Eisler Capital’s Wisnia had come through one of the grandes écoles and had memorised a vast amount of maths in order to do so.

“To get in, I had to learn a large number of mathematical concepts and methods that help you solve exercises like ‘prove that orthogonal matrices are a compact space using Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem’. They are great schools but the focus of training is very much around knowledge accumulation,” he says.

El Karoui’s students quickly discovered that she had very different expectations.

When Wisnia was facing his first exam, he asked El Karoui whether she could give him any past papers, to help him prepare.

“She said, ‘If you really want to become good at this game, Sam, don’t look at past papers and instead just focus – for hour after hour – on understanding very deeply the fundamental sense of the theories I’ve been teaching you.’ And that was really her way of teaching. Nicole was focused on students gaining a deep understanding of the essence of probability theory, the fundamental concepts underpinning derivatives pricing – like self-financing replicating portfolios – and the relationships between those two fields,” he says.

The latter point is crucial. El Karoui was not pushing her students to understand maths for the sake of maths – it wasn’t about formal perfection – it was about equipping them to select the best tool for whatever practical problems they would encounter in the market. And those problems were always the starting point.

Mathematicians – and their teachers – often get it the wrong way round, says Bruno Dupire, head of quantitative research at Bloomberg. He uses Maslow’s hammer to illustrate – the metaphor in which the hammer is a method or principle, and the nail is a problem or question.

“Very often, mathematicians have a hammer, or they find a hammer independently of the nail, and they desperately try to justify using that tool by inventing problems that are usually not very relevant. But I deeply believe that it's very important to start from the nail and then to find the proper hammer – to know what tools exist that could be useful, and if the right tool doesn’t exist, then to create it yourself. To do that, you need people like Nicole, who have this ability to understand real problems and the theoretical capacity to identify the solution,” he says.

At the time, bank trading floors were in dire need of more people like that, and the DEA El Karoui was the first programme to recognise it.

“Banks couldn’t find those people elsewhere. Today, stochastic calculus is mainstream, but it’s mainstream because of finance. There are very few other areas of industry where you need it,” says Bergomi at Squarepoint Capital. “Back then, banks could have hired some engineers, people that were mathematically well-rounded, but certainly, with no specific focus on stochastic calculus, Monte Carlo simulations, and all those probabilistic tools that are very specific to derivatives. They were really after those skills.”

Bergomi would know – he was one of the guys who was trying to hire. As the head of quant research for equity derivatives at Societe Generale, Bergomi typically had room for one or two interns each year. But other teams across the bank were also in the market, as were other banks, of course.

The DEA El Karoui quickly became the main source of quant talent for French banks in particular – helping establish them as financial engineering powerhouses in the decades that followed. Bergomi estimates that, if 80 students graduated from the programme in a year, around a quarter of the class would end up at SG. For his own team specifically, he says somewhere north of 90% of the master’s grads he hired during his two decades at SG were from El Karoui’s course.

“Competition was fierce. Even for internships it was very fierce. Basically, in Paris, in London, we all wanted the same type of animal – someone from that particular master’s degree, and ideally someone who had gone through the École Polytechnique before that. In a class of 80, there might be 15 with that profile – and we all wanted those 15 people,” he says.

To get first dibs on El Karoui’s candidates, banks and other firms would vie for a coveted speaking slot in the weekly practitioner-led seminars that were compulsory for students to attend. They still do today.

Bergomi joined one on October 4, for Squarepoint. Eisler Capital was represented on November 17. By the time their first term ends in December, this year’s students will also have met representatives from Bank of America, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Man AHL, Morgan Stanley and Natixis, among others.

Eisler Capital employs around 80 quants, out of a total workforce of roughly 300, says Wisnia. At least a dozen of the firm’s current crop of quants graduated from El Karoui’s programme.

“Nicole’s teaching became the bedrock of the entire engineering of the sell-side derivatives industry,” he says. “As of today, it’s still an incredibly relevant course. The hires we’ve made have been very successful and acclimate well.”

Lifting the mental load

One reason for the success of El Karoui’s teaching methods was that they came naturally – she was drawing on her own experience and convictions about how to be a researcher. One particular example is the 1998 paper, The Robustness of Black-Scholes, co-authored with Monique Jeanblanc‐Picquè and Steven Shreve, and cited more than 500 times in the years since. The paper explores why the famous pricing approach generally works well as the basis for hedging, despite its widely recognised flaws: in short, a convex position will be hedged correctly as long as the volatility is somewhat overestimated.

“I teach it every year in my course and I think every course in option pricing should teach it," says Rama Cont, professor of mathematics at the University of Oxford – and another graduate of El Karoui’s programme.

The paper may demonstrate a truth that practitioners already knew – that hedges based on Black-Scholes generally worked – but El Karoui and her colleagues were able to explain why, and go beyond that to describe the mathematical foundation for other key options trading practices.

I teach The Robustness of Black-Scholes every year in my course and I think every course in option pricing should teach it

Rama Cont, University of Oxford

Cont adds: “It means hedging is really not about having a precise statistical model. If you use Black-Scholes for hedging, then the only thing you need to estimate is an upper bound for the volatility. They also gave a formula to measure how much a strategy will lose if volatility is under- or overestimated: the leakage is proportional to the gamma of the position and justifies the whole idea of gamma hedging.”

Eisler’s Wisnia calls it “one of the best papers ever written”.

Her other most-cited works were all produced in the years immediately before the Black-Scholes paper. From 1995 to 1997, El Karoui and a variety of co-authors published papers on backward stochastic differential equations – one of these has been cited more than 3,000 times – on changes of numeraire and probability measures in option pricing, and on the pricing of contingent claims in incomplete markets.

One reason for the disproportionate popularity of those early papers is that there were still big gaps in the theoretical underpinning of derivatives markets – quants were racing to lay down track while the trains were already rolling. It was easier to establish new ideas, and for markets to adopt them.

“In that first period, the market was in start-up mode – new activity, new IT tools, new organisation – but after 2000 it became an industry,” says El Karoui. “When you have that big, industrial structure, it is more difficult to introduce new ideas – and new behaviour – because it has to be understood and adopted by a lot of people. It is easier to make incremental changes, which are closer to the existing standard.”

That doesn’t mean there are no gaps, of course – or that all existing standards are flawless. El Karoui has continued to be a prolific researcher, covering an expanding range of topics – a more recent interest is mortality and longevity problems in life insurance, and she sees plenty of opportunity in finance for young quants.

But the topic she speaks most passionately about is the need to bring more women into science generally – and mathematical finance specifically.

I think now is the time for women to take responsibility, to take the initiative, and try to explain where the difficulties are in daily life

Nicole El Karoui

After she became a professor, El Karoui experienced less of the crass sexism that had been her lot in the classes préparatoires, but she continued to face obstacles that most men in the field did not. As well as being a renowned mathematician, El Karoui is the mother to five children, born between 1970 and 1987.

While her children were young, she sought to rigidly separate the two spheres of her existence. When she was at home with the children, then she was with the children; when she was working – often while the rest of the household slept – then she was working. (She worries that the rise of flexible working, and widespread access to phones and communication platforms might make this separation more difficult for working mothers today.) And as the children grew older, they also became better-able to look after each other.

But it remains the case, she argues, that parenting duties and responsibilities generally fall more heavily on women. She’s not just referring to physical activities like feeding, playing and cleaning, but also the mental load that goes with parenting – scheduling, organising, fretting. While the physical tasks can be boxed away into discrete blocks of time, it’s much harder to do the same with that mental load.

The invisible burden has a visible effect. El Karoui takes aim at the popular wisdom that mathematicians do their best work while they are young – prior to the age of 30.

“I think the mental load for mothers is a non-negligible part of the problem, because I’ve had a lot of time to observe a lot of women – and many produce their best work after the age of 40, when their children are more independent, when daily care is less important,” she says.

Obstacles of this kind create a feedback loop: until there are more female role models in science and mathematics, fewer women will feel it is a viable choice; if the number of women in the field does not increase, then there is less need for change, making it harder for role models to break through.

El Karoui urges women who currently work in maths and finance to take some of the responsibility for breaking the loop.

“We must not be passive in confronting these problems. I think now is the time for women to take responsibility, to take the initiative, and try to explain where the difficulties are in daily life. If women are able to explain these details, then maybe we will find it’s not so complicated to modify those things,” she says.

She gives a real-life example of moving the start-time for an afternoon seminar from 17:00 to 16:30, enabling parents to collect children from school afterwards.

“This kind of detail is important. I proposed changing the time, and afterwards it was easier for many people,” she says.

The spirit in which she makes these calls is typical of her – it’s not just about fundamental questions of fairness, but also of effectiveness in research. Again, it comes back to her belief in the liberating power of diversity.

“If work can be organised in such a way that it is convenient for all people, and you are able to have a mix of people who are working together happily, then the results are exceptional. It opens the mind.”

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Awards

Joining the dots: banks leverage tech advancements for the future of regulatory reporting

The continued evolution of regulatory frameworks is creating mounting challenges for capital markets firms in achieving comprehensive and cost-effectiveawa compliance reporting. Regnology discusses how firms are starting to use a synthesis of emerging…

Markets Technology Awards 2024 winners' review

Vendors spy opportunity in demystifying and democratising – opening up markets and methods to new users

Derivatives house of the year: JP Morgan

Risk Awards 2024: Response to regional banking crisis went far beyond First Republic

Risk Awards 2024: The winners

JP Morgan wins derivatives house, lifetime award for El Karoui, Barclays wins rates

Best product for capital markets: Murex

Asia Risk Awards 2023

Technology vendor of the year: Murex

Asia Risk Awards 2023

Best structured products support system: Murex

Asia Risk Awards 2023

Energy Risk Asia Awards 2023: the winners

Winning firms demonstrate resiliency and robust risk management amid testing times