US gas price reporting drop raises questions about indexes

Jitters about regulatory risk have caused a growing number of energy firms to stop reporting their US natural gas trades to Platts and other index publishers. As reported transaction volumes fall, can the indexes still be trusted?

Index publishers such as New York-based Platts and London-based Argus Media play a peculiar role in global commodity markets. By publishing daily prices for a huge variety of energy commodities – from seaborne cargoes of Brent North Sea crude oil to natural gas delivered to the Houston Ship Channel – they shed light on otherwise opaque markets and provide pricing data used by thousands of market participants. Financial firms that would never touch a barrel of physical oil rely on them too, since immense volumes of futures and over-the-counter derivatives refer to indexes published by Platts, Argus and their competitors, which are also called price reporting agencies (PRAs).

The peculiar thing about that arrangement is that it all rests on an uncertain foundation. The indexes so crucial to commodities trading would not exist without voluntary co-operation between physical market participants and the index publishers. When, in a particular commodity market, many firms choose to report their trades to PRAs, the resulting indexes are seen as robust, trustworthy and all but impossible for any single player to manipulate. But, by the same token, if companies stop trading that commodity or decide not to report, the pool of liquidity underpinning the index will diminish and market participants may begin to question whether it is a truly representative benchmark.

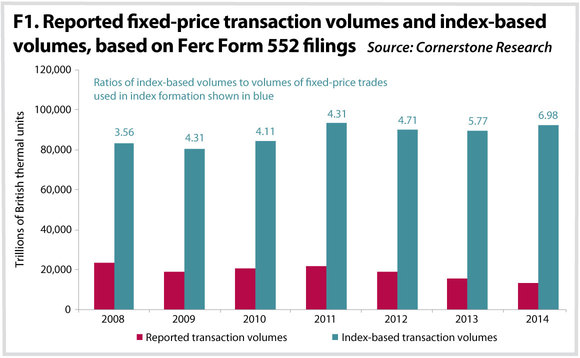

That's why North American energy firms find it so worrying that the number of US natural gas trades being reported to index publishers is dwindling. In 2014, the volume of reported trades fell 15% compared with the year before, making it the third consecutive year in which reported volumes declined, according to a July 14 report by Cornerstone Research, a San Francisco-based consulting and analysis firm (see figure 1, below). While there are various reasons for the decline, one of them is a drop in the number of companies willing to report. Last year, 112 firms engaged in price reporting in the US natural gas markets, down from 133 in 2009, says the Cornerstone report, which is based on company filings with the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (Ferc).

Justin Leonard, Houston-based head of trading in BP's North American gas and power business, finds such numbers troubling. "If the current trend were to continue, that would be an unhealthy outcome for the market," he says. "We support the methodologies that the gas index publishers have in place and we believe they're working today, but we don't want to take that status for granted. It's important to make sure these indexes are available to the industry going forward."

Unfortunately, today's regulatory environment seems to be discouraging companies from reporting their trades. Both Ferc and the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) have stepped up their enforcement activities in recent years, and Ferc in particular has extracted hundreds of millions of dollars in fines from energy firms accused of market manipulation in the past half-decade. Lawyers and compliance managers say the stricter regulatory atmosphere is pushing companies to curb price reporting for fear that it exposes them to legal risks, including the risk of a costly manipulation fine.

We have heard that a lot of companies have elected to cease reporting due to the perceived regulatory risk

"Many market participants view price reporting as a risky endeavour from a compliance perspective," says Michael Yuffee, a Washington, DC-based partner with law firm Reed Smith. "The size of Ferc's penalties certainly scares some market participants. So something like price reporting, which isn't mandatory, is definitely an area that compliance officers are looking at to see whether it's an activity they want their companies to be doing."

'Ample liquidity'

Three PRAs publish the most widely used indexes in US natural gas: Platts, the dominant player in the space, owned by New York-based McGraw Hill Financial; Natural Gas Intelligence (NGI), a smaller but long-established PRA, owned by Virginia-based Intelligence Press; and Argus, which began covering US natural gas in 2009. All three confirm they have seen a reduction in companies' willingness to report, but stress that the size of the reduction has been small and that their indexes remain accurate measures of underlying markets.

"While we have experienced a small decline in the number of companies that report transactions, we still see ample liquidity in the natural gas market and Platts is confident that it is able to produce assessments reflective of market value," says Mark Callahan, Platts's Houston-based editorial director of North American power and natural gas pricing.

The PRAs push back against the suggestion that perceived regulatory risk is driving the fall in reported volumes. The more important factor, they say, is a broad shift away from reportable fixed-price deals and towards index-based pricing.

"NGI has experienced some decline in reporting as more companies index and therefore have only de minimis reportable transactions," says Ellen Beswick, Virginia-based publisher and editor-in-chief of Intelligence Press. "We have lost just a couple [of] companies over the last several years that decided not to report for their own business reasons."

Several factors have led to a greater use of index-based pricing, the index publishers say. One of them is the shale revolution, which has led to well-supplied gas markets and dampened volatility. That has made consumers more willing to buy volumes of gas at floating prices linked to indexes, rather than locking in prices with fixed-price deals. In addition, the changing mix of market participants – in particular, the retreat of banks from commodities trading – has been a contributing factor.

"Many of the banks, which previously would have taken on that risk, have got out of this market," says Caroline Gentry, Houston-based vice-president of business development at Argus. "The banks like to do fixed-price trading because their goal is to make money. The utilities, and to a certain extent the producers, like tying what they can to index, because there's no risk that they'll buy above it or sell below it."

Cornerstone's report also highlights the retreat from fixed-price deals in favour of index-based trading. In 2014, some 78% of US physical gas transactions relied on index prices, up from 74% the year before, the report says. By comparison, direct fixed-price deals accounted for just 16% of transaction volume last year, down from 19% in 2013.

That leads to an "imbalance", says Cornerstone. PRAs are constructing their indexes based on a shrinking proportion of reported trades, yet the share of deals linked to their price assessments is growing. In 2014, the volume of index-based trades was 6.98 times the volume of trades that formed the indexes – a ratio that has nearly doubled since 2008, when it was just 3.56, Cornerstone says. Notably, the numbers cited by Cornerstone reflect only physical gas trades, not the broader universe of futures and OTC derivatives that also rely on the PRAs' indexes.

Some interpret the shift towards index-based pricing as a vote of confidence in the PRAs. "It is possible, perhaps, that we are victims of our own success and it is precisely [the fact] that the published indexes are transparent, robust and reliable that has contributed to the increased reliance on indexing, which in turn reduces the fixed-price trading available to comprise the index," says NGI's Beswick.

But others worry that market participants are flocking to indexes that may not be consistently reliable. "What's troubling is if companies blindly price off an index as if on auto-pilot, without considering the data or fundamentals that underlie the index," says Jennifer Fordham, senior vice-president for government affairs at the Washington, DC-based Natural Gas Supply Association.

Fordham agrees with the PRAs that a broad shift towards index-based pricing is partly to blame for the decline in reported volumes. But the other part of it, she adds, is the mounting fear that price reporting could become a source of legal and compliance headaches. "We have heard that a lot of companies have elected to cease reporting due to the perceived regulatory risk," she says.

Energy crisis

Much of the regulatory framework around price reporting in US natural gas markets stems from the western US energy crisis of 2000-01, in which a bungled liberalisation of California's power market led to rolling blackouts and allegations of widespread manipulation. Following the crisis, it emerged that traders at numerous companies had fed false information to PRA publications, particularly Platts's Gas Daily and Inside Ferc, in a bid to influence index prices. A 2003 report from Ferc found that there had been an "epidemic of false reporting" and that such falsification had been routine and openly carried out by traders at merchant energy firms. The CFTC eventually collected tens of millions of dollars in fines from the companies involved, and several traders were even jailed on fraud charges as a result of false reporting.

Amid the storm of regulatory scrutiny, energy companies became understandably nervous about price reporting, and the amount of transaction data being reported to PRAs dropped sharply, hitting a low in late 2002. Ferc consulted with the industry and considered several options for restoring trust in US gas indexes. The most radical option was to replace voluntary reporting with a mandatory regime.

Ultimately, Ferc did not go that far. Instead, the regulator settled on the so-called 'safe harbour' policy, which was issued in 2003 and further clarified in 2005. Under the policy, Ferc said it would not penalise companies for inadvertent errors in price reporting as long as they committed to report transactions in good faith and completely – meaning they could not cherry-pick some trades to report while leaving others unreported. Market participants, as well as the index publishers, say the safe harbour policy helped nurse US natural gas indexes back to health.

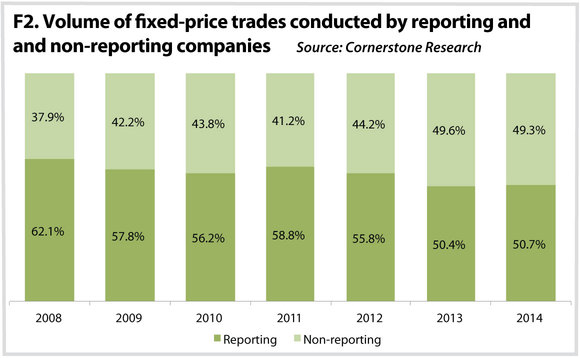

The recent fall in price reporting has been much more gradual than the precipitous collapse that took place in 2001–02. Cornerstone estimates that in 2014, index publishers still managed to capture 50.7% of all fixed-price physical gas trades that could have been reported by volume – a sizeable percentage, though down from 58.8% in 2011 (see figure 2). Moreover, PRAs still command the loyalty of most large market participants, which means they receive data on a significant proportion of volumes, even if the actual number of companies reporting is relatively small. In 2014, eight of the 10 largest market participants engaged in voluntary price reporting, says Cornerstone. That included oil majors BP and Shell, whose US trading units were the largest and second-largest participants by volume, respectively.

Who has stopped reporting?

Energy companies are generally reluctant to comment on their price reporting policies, but evidence of who is and isn't reporting can be gleaned from an annual filing called Ferc Form 552. Any company whose annual US physical gas purchases or sales exceed 2.2 trillion British thermal units must file Form 552 once a year. When submitting the form, firms must indicate whether or not they report to index publishers. Cornerstone's report is based on Form 552 flings, and the filings are also closely watched by the index publishers themselves.

According to their Form 552 filings, firms that have opted to stop price reporting in the past five years include: Direct Energy, the Houston-based electricity retailer owned by UK utility Centrica; Dominion, the Virginia-based utility; Exelon, the Chicago-based power generation and distribution firm; GDF Suez Energy North America, the Houston-based subsidiary of French utility Engie; Iberdrola USA, the Maine-based arm of Spanish utility Iberdrola; Net Midstream, the Texas-based pipeline operator; and Powerex, the British Columbia-based trading arm of Canadian utility BC Hydro. Two of those companies – Direct Energy and Exelon – confirm that regulatory risk was part of their thinking when they decided to stop price reporting.

"In 2005, Ferc put in place certain safe harbours to help facilitate price reporting, but an entity still has a certain amount of regulatory risk with price reporting," Direct Energy said in an emailed statement. The firm added that its decision was linked to its 2013 acquisition of New York-based Hess's energy marketing business, which significantly increased Direct Energy's footprint in natural gas. Once the integration of the Hess assets is completed, "we would have to analyse the safe harbours and additional risk of price reporting, then weigh that risk with the benefits of voluntary price reporting", Direct Energy said.

Meanwhile, Exelon said it had given up voluntary price reporting in 2012, "based on the volume of the company's natural gas trading activities and regulatory compliance issues associated with such reporting".

Among the other companies, GDF Suez said it stopped reporting because it decided its "resources were better used for other purposes". Powerex cited "internal reasons" for the decision but did not elaborate. Dominion, Iberdrola and Net Midstream declined to comment.

In some cases, firms that previously reported to the index publishers stopped doing so after being acquired by other firms that had the opposite policy. Form 552 filings show that Houston-based power producer GenOn ceased to report after it was acquired by New Jersey- and Texas-based NRG Energy in 2012, for example. NRG – whose filings indicate it does not report – declined to comment.

One Houston-based compliance manager with an energy company that chose to stop reporting in the past several years also attributes the decision to regulatory risk. "We were very much a proponent of price reporting because it helps keep the markets more transparent," the compliance manager says. "But it was just felt that we did not need that type of exposure."

Regulatory risk

Ferc says it is keeping an eye on the Form 552 data but so far sees no reason to be concerned. "Although index reporting has declined, there are still over 100 reporting companies, as noted by Cornerstone," says a Washington, DC-based spokesperson. "We are monitoring the situation."

The Ferc spokesperson disputes the claim that price reporting leads to heightened regulatory risk. "The commission doesn't initiate investigations or audits based on whether a company chooses to report to index publishers or not," the spokesperson says. "However, if a company intentionally misreports their fixed-price data, it could be a subject of an investigation."

Lawyers say it's not quite that simple, however, and they point to a number of potential risks that arise when a company chooses to report to PRAs. For one thing, Ferc periodically conducts Form 552 audits. Such audits target both reporting and non-reporting companies, but reporting companies have more to worry about during an audit because they must demonstrate that transaction data they submitted to index publishers was accurate.

Another major concern is the risk of a costly manipulation penalty stemming from a company's price reporting activities. In the past few years, Ferc has sought to impose eye-popping fines on firms accused of manipulation. Most notably, it is seeking to collect $470 million from Barclays over allegations that the UK bank's traders manipulated power markets in and around California from 2006 to 2008 – accusations that Barclays strongly denies and is fighting in court. Such enforcement actions are a result of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, a law that authorises Ferc to prosecute market manipulation and impose fines of up to $1 million for each day that a company is found to be manipulating wholesale power or gas markets.

Price reporting could lead to a manipulation case in several ways, lawyers and compliance managers say. A misreported trade, for instance, could lead Ferc to suspect that a trader was submitting false information, as in the cases that arose in 2000-01. Even though the safe harbour policy offers some protection against such a scenario, it also says that companies should correct reporting errors "as soon as practicable" – a standard that might be difficult to meet.

Another way in which price reporting could result in a manipulation case, lawyers say, is if a company is found to be abusing market power. For example, an energy company might be a major trader of natural gas at a thinly traded hub. If the company reports to PRAs, it would play a significant role in setting the index price for that location. Then, if regulators spot the company losing money in physical trades at the hub while profiting from financial positions tied to the index, they could accuse the company of market manipulation, with price reporting playing a crucial link in the alleged manipulative scheme.

John Estes, a Washington, DC-based partner with law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, warns that such scenarios could become more common if more and more companies opt out of voluntary price reporting. "As the ranks of those who report thin, the people who remain have a bigger market share, just by default," he explains. "And the larger a share you have of index-reported transactions, the more likely it is you will hit market surveillance screens at Ferc and the CFTC. So just by remaining on the scene, you end up having increased regulatory risk, even though you're not doing anything wrong."

Some say Ferc could mitigate the retreat from price reporting by strengthening the safe harbour policy. "Updating the safe harbour policy and making it more definitive could give market participants more comfort about voluntary price reporting," says Reed Smith's Yuffee. "The safe harbour policy pre-dates the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and the anti-manipulation rule that Ferc adopted in 2006, so it doesn't specifically address manipulation. If the safe harbour policy can be tied to Ferc's anti-manipulation rule and offer some protection against it, that would be helpful."

Until that happens, though, index publishers will just have to hope that the retreat from price reporting doesn't go too far. Bradford Leach, a principal at Energy Advisory Services, a Connecticut-based research firm that studies market liquidity, expresses sympathy for the PRAs' position. "One of the issues with running a PRA is that there is no state or federal regulation that compels reporting," he says. "So the PRAs are stuck with who's out there and who's reporting prices."

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Energy

Energy Risk Commodity Rankings 2024: markets buffeted by geopolitics and economic woes

Winners of the 2024 Commodity Rankings steeled clients to navigate competing forces

Chartis Energy50

The latest iteration of Chartis’ Energy50 ranking

Energy trade surveillance solutions 2023: market and vendor landscape

The market for energy trading surveillance solutions, though small, is expanding as specialist vendors emerge, catering to diverse geographies and market specifics. These vendors, which originate from various sectors, contribute further to the market’s…

Achieving net zero with carbon offsets: best practices and what to avoid

A survey by Risk.net and ION Commodities found that firms are wary of using carbon offsets in their net-zero strategies. While this is understandable, given the reputational risk of many offset projects, it is likely to be extremely difficult and more…

Chartis Energy50 2023

The latest iteration of Chartis' Energy50 2023 ranking and report considers the key issues in today’s energy space, and assesses the vendors operating within it

ION Commodities: spotlight on risk management trends

Energy Risk Software Rankings and awards winner’s interview: ION Commodities

Lacima’s models stand the test of major risk events

Lacima’s consistent approach between trading and risk has allowed it to dominate the enterprise risk software analytics and metrics categories for nearly a decade

2021 brings big changes to the carbon market landscape

ZE PowerGroup Inc. explores how newly launched emissions trading systems, recently established task forces, upcoming initiatives and the new US President, Joe Biden, and his administration can further the drive towards tackling the climate crisis